|

Preaching on: Mark 1:29–39 We’re only in Mark, chapter one. Mark, chapter one. Jesus has hit the ground running. He has called his disciples, he has taught in the synagogue, he has cast out demons, he has cured the sick. He has already had to sneak off in the dark to get a little peace and to pray. And when his disciples find him, they tell him, “Everyone is searching for you.” Everyone is searching for you.

I wonder if that line is true in some larger sense than the disciples could have imagined. I wonder if everyone is searching for Jesus. I believe that everybody is searching—or at least hoping—for something. The condition of many people outside of the Church, or another religious tradition, is that they don’t necessarily know what it is exactly that they’re searching for. But they’re all searching for something that will satisfy some deep longing within them. And the condition of many people inside of the Church is that because the answer to the question has been provided to us all along (Jesus is the answer, of course) and we didn’t necessarily have to discover it for ourselves, many of us have not truly experienced the question that I believe Jesus is the answer to. And so we’re something like the people of the planet Magrathea in Douglas Adams’ novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. After waiting 7.5 million years for their supercomputer, Deep Thought, to produce the ultimate answer to the question of life, the universe, and everything, the computer spits out the response “42.” 42? After expressing dismay that they’ve waited 7.5 million years for the number 42, Deep Thought explains to the Magratheans that this is indeed the answer, and that the problem is simply that they don’t truly understand the question yet. And so the possibilities in my mind of these two groups of people getting together are limitless. On the one hand, the unchurched seekers who are walking the streets every day trying to find their way and longing for a sign to point them in the right direction. On the other hand, the churched seekers who have long held and studied the map of the city and who long to experience the profound miracle of being lost and then found. If we mix the questions and the answers we’re going to get a chemical reaction that produces energy, light, heat. In other words, transformation. Soren Kierkegaard, the great 19th century Danish philosopher, theologian, and existentialist argued that truly hearing and responding to the Christian message demands a personal transformation, a leap of faith that sets one apart from the crowd. This is a challenge in a Christian environment or culture, where Christianity is often taken for granted and not lived out in the radical manner that Kierkegaard believed the New Testament portrays. In Kierkegaard's view, the very familiarity of Christianity paradoxically makes it more difficult for individuals to genuinely engage with and understand the Christian message. He believed that in spaces where everyone is considered a Christian by default, the radical and demanding nature of true Christian faith is often watered down or ignored. Kierkegaard has convinced me that if the story of how we came to be Christians and the story of how we got to the answer of Jesus is simply that we were raised in a Christian land or in a Christian church, instead of a story about a radical encounter with a God who heals, exorcises, and saves, with a God who has transformed your life, then our story will always lack the existential depth and commitment to be able to convince anyone (including very often ourselves) that our answer matters. If I’m right about this, then the unchurched should be able to find Jesus inside this sanctuary. But only if those who are churched and holding the answer have first found Jesus outside the sanctuary—Jesus not in the form of an answer, but Jesus in the form of “the least of these,” Jesus in the form of human beings living, and enjoying, and suffering a human life. Jesus can only be convincingly offered as the answer if those who hold that answer have truly experienced the question for themselves and the transformation that comes when the key is fitted to the lock and the door that blocked your way is finally opened wide. Do you believe that Jesus is the answer? If so, what question or what experience or what deep longing in your life has Jesus provided the answer to? It’s the answer to the second question that makes your answer to the first question matter. No one is going to care that Jesus is our answer unless we back that answer up with a story, with an experience, with some measure of devotion and love scratched out of the hardships of this life. That’s why addicts in recovery are some of the best evangelists. Because they’ve lived and suffered through some of the worst experiences of what it’s like to try to satisfy the terrifying longing at the center of life with stuff (like drugs and alcohol) instead of with (what the 12-steps call) your “higher power.” To me, Jesus the answer must always be secondary to Jesus the question. And that means, as a church, we should orient ourselves first and foremost toward those who question, rather than orienting ourselves first and foremost to those who have the answer. We should prioritize those who seek, rather than those who have found. We should prioritize our own doubts, our own questions and experiences, our own failings and longings. We should tell these stories to one another. We should tell these stories in church. Because nobody wants an answer from somebody who doesn’t seem to understand the question. Everybody is searching for something. And Jesus is an answer available to every person that can bring profound meaning, comfort, healing, challenge, love, and purpose to our lives. Whether we are unchurched and longing for an answer or churched and longing to experience our answer actually transforming our lives, we are all searching for Jesus. And we will find Jesus most fully when we come to embrace the true meaning of what it means to be searching for Jesus—the simultaneous experience of being both lost and found. This is the point of convergence where transformation can happen for all of us, where Jesus ceases to be an answer and becomes what he truly is—the experience of everything that truly matters and the grace and love that surround us all.

0 Comments

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.”

Now about three years ago I preached a sermon on the fear of God—the exact topic was put forward by our own Craig Wood who asked, “How can we fear God and love God at the same time?” A great question. And in response I guided you away from fear and towards love. I told you all that we’re not supposed to be abjectly terrified of God. And it’s deeply unfortunate that some of us have been raised in traditions where we’re made to feel afraid of God and God’s righteousness and anger and ability to punish us in life and in death. And I explained that there’s actually a translation issue going on here. The ancient languages had fewer words than we do in our modern languages. Modern English has 170,000 words in current usage. Ancient Greek, the language of the New Testament, had about 60,000 words—110,000 fewer words. Ancient Greek was a less precise, more metaphorical and poetic language than modern English because every word had to do more work, it had to carry more meaning. There was no Ancient Greek word for “awe.” There was no Ancient Greek word for “reverence.” There was no Ancient Greek word for “numinous.” There was no way to say in Ancient Greek, “And it was an awe-inspiring sight.” They literally didn’t have the words. So, how would they convey the meaning? They’d have to say something like, “And seeing the angel he fell down quaking in fear.” So, the word that meant “fear,” in certain contexts, had to mean more than just fear; it had to point at these more complex, nuanced feelings. When we read about fearing God, it's about having profound respect, awe, reverence in the presence of the Almighty, it’s not about being afraid of God. Don’t ever confuse love with fear, I told you—that can lead to some very unhealthy relationships. And the fact of our faith is that you don’t need to be afraid of loving our loving God. MMM. That was a good sermon, right? But one sermon can never say it all. One criticism I could make of my sermon three years ago was that it was a little too tidy. And folks like a tidy sermon—I get it. But God is almost never tidy. And so this Sunday I’m going to try to bring back—to recommend to you all a little bit… a little bit of fear. The fear of God means awe before God, reverence to God, yes. AND it also means FEAR. We can’t dismiss that. It’s too big a clue to ignore. There’s a reason that the word “fear” in the ancient languages carried these other ideas of awe and reverence. It wasn’t chosen at random. It could never have been, “The happy-happy, joy-joy, good time of God is the beginning of wisdom.” Those feelings just don’t live in the right neighborhood. Is God a source of happiness? Yes. Is God joy? Yeah. Is being with God a good time? Sure. AND if you want to find awe, if you want to feel reverence, if you want to come into the presence of the God who is in all things and beyond all things, if you want to get to wisdom, occasionally you’re going to need to go looking in fear’s neighborhood. And the psalmist suggests to us this morning that fear’s neighborhood might just be a good place to start. Jesus taught us that God is our loving, heavenly father. And this wasn’t something we had ever really encountered before. And he taught us this as a corrective measure—not in terms of gender, of course (you can’t do it all), but in terms of the attitude of God. God is not distant or aloof. God is not an untouchable king, not a cold judge, not an alien power. God is as close, as warm, as intimate, as caring, as involved as a loving parent is. It’s a strong spiritual medicine, meant to bring us back into harmony, but not to utterly erase the other Biblical traditions of God. So, we don’t need to fear our loving, mother-father God. And yet God is so much more than any one metaphor or symbol. It is beyond our ability to put God into a box, to tidily label God and then say to God, “God you will behave according to this metaphor and this metaphor only. Don’t show up in my life as anything scary. That’s not allowed.” Now, I assure you that God doesn’t want us to cower in fear in God’s presence. But fear is a perfectly natural reaction of very small, mortal creatures like ourselves when we come into contact with a God who is ultimately wholly and utterly beyond the tiny little boxes that define our reality. And it is, in fact, spiritually healthy for us, from time to time, to tremble in the presence of a loving God who opens all our boxes, unties all our knots, overflows all our containers, and reminds us that anything is possible and perhaps our most cherished ideas about what is true, about what is real, about what is just, about the ways we should live, and what is important, and what is meaningful are not total, are not complete. In the presence of a God who is so wholly other, so completely beyond us, we may even feel something like terror. And yet if we are not overwhelmed by fear, if we don’t go running away, grasping to our own ideas and our thinking, refusing to let God take control, we will also feel the mercy of being relieved from our illusions that we can do it all our own. Once you have truly felt the fear of God, you begin to understand the truth of grace—you will see that our existence depends totally on a Mystery we will never fully understand or control. And that is an awe-inspiring sight. So, this morning I’d like to recommend to you, on occasion, to seek out situations or experiences that make you tremble a little. When I stand in my back yard here in New Jersey, and I look up into the sky at night, so bright with city lights, full of the roar of airplanes, I don’t feel a thing. But out in the woods, in the wild, in the mountains, the sky at night is bigger, vaster, deeper, scarier. It’s not just a few bright stars you see, you look up into the vastness of the universe. Everyone should find a dark spot at least once a year to look up into the night sky, to see the Milky Way, and to feel almost impossibly small, lost in the vastness of creation that is full of the vastness of God. Light pollution is a spiritual problem. We’re so enlightened! We think we have all the answers. But sometimes our light just closes our eyes to the true reality of the problem. We edit the big sky out of our lives. We stop looking up. Something that made me tremble once was a silent meditation retreat. For a full-day, we sat in complete stillness and silence, facing the wall and focusing on our breath. And in that deep stillness, I could feel the fear creeping in. Fear of my own thoughts and emotions, fear of the unknown, fear of facing myself without any distractions or noise. I had these bizarre fantasies around lunchtime about having a medical emergency that would force me to leave. It was terrifying and eye-opening at the same time. And in that fear, I found a deeper connection to God, a sense of awe and reverence for my own existence and for the vastness of the universe. It was a powerful reminder that sometimes we need to let go of our comforts and persist through fear in order to more deeply understand ourselves and God’s presence in our lives. I don’t know what the right experience is for you, but I recommend you seek out the opportunity to tremble a little in God’s mysterious presence. I recommend experiencing whatever emotions you feel when you open up your grasping hands and let God truly define you and your life. Step into the vastness of God's presence, and allow yourselves to be moved, to be challenged, to be transformed. This is the beginning of wisdom—a journey not away from God in fear, but towards God, with a heart full of reverence, love, and awe. Our reading from the Psalms this morning asks us to wait in silence for God—to rely totally on God and God’s action. Salvation comes from God—not from this world, not from my own effort, not from anything else other than God. So, I must faithfully wait.

In our reading from 1 Corinthians, Paul suggests that we run like we were in a race—to win it. We should train (as hard as athletes do) for the gold medal of salvation. And we shouldn’t just take one of those popular boxing classes where you punch the bag but nobody ever actually takes a swing at you. We need to get into the ring and really compete so that we can become masters of ourselves. Paul proclaims the gospel of Jesus Christ to others, but fears that if he doesn’t live the gospel out in sweat and blood, in effort, and in self-mastery that the gift he offers others may be denied to him. So, which is it? Should I take the advice of the psalmist and rely totally on God and God’s grace? Or should I follow Paul and make every human effort possible to win salvation? Growing up in church as a kid, I mostly got the message that the most important thing was to have faith—faith in God, faith in Jesus, to believe. And I did believe. But by the time I was in high school I was beginning to see the world more clearly—how broken and violent and corrupt and unjust it was, all the suffering of God’s people around the world—much of it preventable, much of it caused by us—other people. Suddenly it felt like my faith alone wasn’t enough. If I really believed in a God who was bigger than me and was best described as love and righteousness, was lip service to the Kingdom of Heaven really enough? It felt hypocritical to say that I believed in the Bible but that I believed in the Bible so much—in faith alone—that I was somehow exempted from living out the Bible’s full vision for God’s people. It was like saying, “I believe totally in vegetarianism” while eating a hotdog and not seeing a problem there. At some point you’ve got to put your money where your mouth is, right? Like Paul says, you’ve got to go all in. It felt to me like the church knows how to talk the talk, but do they really know how to walk the walk? By the time I was in seminary, I knew that faith and grace and waiting in silence weren’t going to be enough for me. I had no plans to ever be the kind of minister who is standing in front of you right now—serving a traditional church. I wanted to actually do something! I wanted to put faith into action! I wanted to be the change! I wasn’t interested in charity or token acts of compassion—“tossing a coin to a beggar” as Martin Luther King, Jr. once famously put it. Like King, I wanted to transform the social and economic systems that reduced people to begging in the first place. I was interested in revolutionary justice—liberation theologies, ending poverty, shoring up workers’ rights, organizing, supporting the voices and the movements of marginalized people. And I poured myself into very left, very progressive Christian and political spaces and organizations for years. I was right where I wanted to be, with extremely dedicated people, sacrificing every day, fighting the good fight, and making a difference. And in those very same progressive spaces, I found a lot of dysfunction, a lot of self-inflicted suffering and pain, and a lot of infighting caused not infrequently by injustice and unfairness in the very power dynamics of the movements that were fighting for justice and fairness. But most devastating of all to me was the endemic burnout and the holistic unhealthiness of all that endless sacrifice and nonstop effort to make the world a better place. And even in the explicitly Christian spaces it felt like the working belief was that it was all up to us. The project of making the world a better place rested entirely on our shoulders alone. Waiting for God? Listening for God? Relying on God? To us that seemed, at best, naive and at worst it was just a way for people to assuage their guilt and let themselves off the hook of their responsibility to love their neighbors as themselves. We believed that somehow faith in God’s grace, in God’s plan, God’s action had gotten in the way of the true path of human responsibility and effort. The ironic consequence of all this was that effort, and good works, and making a difference (which had come to define my faith in God) had now left me so spiritually depleted that they had almost undone my faith in anything at all. I began to reflect and to realize that I couldn’t—we can’t—do it all by ourselves. We need God to be fundamentally involved. Once upon a time, there was an orphaned sparrow who fell out of the nest and was all alone in the world. When it came time for him to learn how to fly, he decided he should seek flying lessons from Eagle who was admired by all the birds for his abilities. Sparrow climbed up to Eagle’s eerie and asked him what he should do to learn to fly. “If you want to fly,” Eagle said, “you must trust the Air and its currents. Stretch out your wings and let the wind carry you along.” The little sparrow followed Eagle’s advice to the letter. For days he simply stood on the ground, stretching out his wings and trusting. Every once in a while, he felt something—a little rustle or breeze—that made him feel sure that he was on the right track. But after days of waiting with his wings out, he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere. One day Hummingbird darted past and saw the little sparrow standing on the ground with his wings out and his eyes closed. “What are you doing?” he asked. “I’m learning to fly!” chirped Sparrow. “What simpleton taught you that that’s the way to fly?” shouted Hummingbird. “Eagle told me I needed to trust the Air, and it’s currents will carry me wherever I need to go.” “Oh, that old superstition!” said Hummingbird with contempt. “Listen, kid, if you want to learn to fly, you’ve got to flap your wings like me.” The little sparrow started to flap his wings and got immediate results. He flapped his wings so fast he sounded like a little helicopter—Whir! Whir! Whir! And to his delight, by the end of the day he was off the ground (Whir! Whir! Whiirr!), and the next day he was in the treetops (Whir! Whir! Whiiirrr!), and by the next day the sky was the limit (Whiirr! Whiiirrr! Whiiiirrrrrr!). But by the fourth day he was so exhausted he couldn’t even lift his wings up from his sides and hold them out, let alone fly anywhere. The little sparrow lay on the ground panting, his dream of flying through the heavens seeming more distant than ever before. That evening, as the sky turned a soft shade of orange and the air cooled, the sparrow felt the gentle caress of a breeze once more. Lying there, exhausted, he didn't worry about the fact that he had proven with his flapping that Air was just a superstition—a crutch for birds who didn’t want to fly; he simply let the breeze envelop him, feeling its subtle power, feeling the way it moved through his feathers, feeling like his whole body was designed to be touched by it. In that moment, as he gave in to the quiet presence of the Air around him, he felt a renewed strength and determination within him. He flapped his wings—once, twice, three times—not a blur of frantic energy, just enough to let the Air know he was there, that he was ready. And then he stretched out his wings and he soared. Rising into the sky he thought he heard the wind whispering to him with every gentle, intentional flap of his wings, “Yes! Yes, little sparrow! Let’s do it together!” In the end, the sparrow's journey mirrors our own spiritual journey. Faith and works are not exclusive; they’re complementary. Faith inspires action, and action stirs up and expresses our faith. We need the wisdom to know when to act and when to be still, when to speak and when to listen. Our faith is not measured by one or the other but in the delicate balance between the two. Too much flapping and we will fall flat. Too much standing around and waiting for Air to do all the work, and we’ll never leave the ground. This is what I’ve learned in my journey. Just like there’s no such thing as flying without air, there’s no such thing as action, or transformation, or revolution, or dreams, or vision, or any kind of change for the better at all without God’s grace. God’s action, I think, is best described like the activity of air: Every once in a while, it gives a mighty blow, but most of the time it’s simply the invisible medium that carries us along, that empowers us to express our faith in the first place. Air is there because it expects us to fly. But if we lose sight of the fact that we were designed to fly through air, we’ll create for ourselves a spiritual vacuum that will leave us stranded. Like the psalmist we must learn to rely totally on God. Like Paul we must endeavor to make every effort. And like the sparrow, we must learn to do both at the same time. In the balance, we find the true freedom to make a difference, to accomplish what seems beyond our reach, held aloft by the love and the power of something much greater than ourselves. You know, it’s funny because I’ve heard this scripture reading so many times in my life. And, of course, I’ve always identified with Samuel. Samuel, the young up-and-comer who speaks with God. Samuel, the golden child, who has his whole life ahead him. Samuel, the chosen one, destined to become a great prophet and leader of his people.

Do you remember when you were young and everyone simply admired all your potential, rather than anything you had actually accomplished yet? That wasn’t so bad! I remember that feeling so well. I remember feeling intoxicated by the possibilities! “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” as Dr. Seuss put it. I’ve always identified with Samuel. But I can’t keep identifying with this child or this young man forever, can I? At some point I have to face reality here. My whole life isn’t ahead of me anymore. I’m somewhere in the middle of things. I’m not all pure potential anymore. I’ve actually had to do stuff—I’ve had to make choices, sometimes tough choices. I’ve come to forks in the road and had to commit myself to the left or the right and leave the other way behind. I’ve had successes. But I’ve also had failures. People don’t admire me for what I might accomplish anymore, they sum me up by my successes and my failures. Yes, I’ve had failures, and disappointments, and realized (slowly, painfully) that I might not be as perfect as I once thought I would be. It turns out that perfection is just that state, unique to youth, before you’ve actually had the opportunity to mess anything up yet. So, as I cross more deeply into midlife, I realize I now have more in common with Eli than I do with Samuel. Eli, with his faults and his foibles and failures. Eli who is getting older, and heavier, and weaker. Eli who had the best of intentions, who always wanted to do the right thing, but who hasn’t always succeeded. Eli, who has now learned of his ultimate fate: After all his service, all the good he has done, he will be judged by his failures rather than by his successes. His end and the end of his line is assured. This wasn’t the dream he had for himself when he was Samuel’s age. We’re getting more and more used to the downfall of powerful and famous men in our culture. Especially since the Me-Too era, each shocking new revelation of personal depravity becomes less and less shocking to us. But, of course, Eli isn’t guilty of anything like that. He is at core a good person who has tried his best. The crimes he is being judged for aren’t even his—they’re his sons’. But today when famous leaders are called out for bad behavior, what’s the next step? They deny it. They fight it. They attack the accusing party, attack the media, attack their political opponents. Not Eli. Eli, who was a fundamentally good man, accepts his fate. “It is the Lord,” he says, “let him do what seems good to him.” I find that incredibly admirable—that willingness, that ability to accept a judgment that must feel like a bitter disappointment, that must feel completely unfair. But Eli accepts his fate. He accepts reality. I heard this wonderful story recently about a friend of a friend. Let’s call her Sarah. And Sarah was in my phase of life—middle-age. And life hadn’t gone the way she thought it was going to go. She had dedicated her whole life to serving the most vulnerable people in our society—people living on the streets without shelter. And it’s hard work. And she had breast cancer. And she’d just had a double mastectomy. And she’s alone without a partner of any kind. And she’s just burned out at the bitter disappointment that life has turned out to be. And so she goes on a trip to Italy. And at her first stop in Sicily she basically accidentally (because she’s not religious) finds herself in a little grotto underneath an old, ruined stone church. And there’s a man down in there—an artist—making angels’ wings. And he tells her that this is what he does all day: he sits under the church crafting these angels’ wings and thinking about the meaning of life. And so she asks him, “Oh really? What is it? What’s the meaning of life?” And in the conversation that ensues she ends up telling this total stranger (who is not the kind of person she would normally trust or open up to) the whole bitter story of her life and her suffering. And when she finishes, this big, burly Sicilian man, wraps her up suddenly in a bear hug, squeezing her chest to his chest. And she’s immediately terrified and uncomfortable, but then she just let’s go and she starts weeping in his arms. And when she’s done, she tries to sort of tap out of the hug. But this guy doesn’t let go, he keeps squeezing her! And something releases in her body, and she breaks down again, but this time she’s not weeping she’s sobbing. And when it passes, she tries to break away. But he still won’t let go. He’s squeezing her and saying, “It’s OK, Sarah. It’s OK. Life is beautiful! Life is beautiful!” And she breaks down a third time, not just crying but convulsing uncontrollably with grief and mourning. And then he lets her go. And he tells her he’s a priest and he takes care of this ruined old church. Why? Well, he takes her down into the catacombs underneath the church where the bones of all the old priests—some going back to pre-Christian times are piled up in the dark. And Sarah realizes she has to run, she needs to catch a train to her next destination. And so she runs out there, and then the rest of her trip through Italy is the most amazing, Spirit-filled adventure of her life. Sarah’s ears are tingling and around every corner there is some person or activity or coincidence that makes it feel like after a long, long silence God is speaking directly to her. What happened? What changed? I think Sarah stopped fighting it. She accepted it—her life, her suffering. She accepted it for what it was. She went down and saw all the old bones of her life piled up in the underworld—the flaws, the failures, the mistakes, the missed opportunities, the disappointments, the losses, the dreams that never materialized, and she accepted them for what they were. Acceptance is the greatest form of release. I think it’s when we refuse to accept the ghosts of our past that they haunt us and refuse to leave us alone. But when we visit them, accept them, and take care of them, we’re able to move on. “It is the Lord,” Eli says, “let him do what seems good to him.” This is not a passive statement. To get to those words, Eli had to do the work of total, radical acceptance of himself—the good and the bad. And Eli, like Sarah, doesn’t give up. Eli doesn’t say, “Well, if that’s the way you’re going to be, I’m just going to go home and wait for death.” He continues to do his job to the best of his ability until the terrible day of the death of his sons in battle and his own death on hearing the news. He continues to mentor Samuel. He continues to give himself to his people and to God. While Eli is one of the most extreme examples of this we can think of, it seems like an important point for understanding how to live life after we’ve accepted we’re not perfect and that life isn’t fair. If you give up, you lose. And the rest of us lose because we lose your experience and your perspective. Perfect people make terrible mentors. Terrible. Perfect people can only mentor perfect people. The rest of us need a screwup—someone who can teach us how to be faithful through disappointment. Which is Eli’s superpower here. When I think of Eli, I think of former president Jimmy Carter who famously transitioned from a one-term presidency into one of the most impactful post-presidential careers in American history. Jimmy Carter, like Eli, faced significant challenges and some might say failures, during his time in office—from economic troubles to political strife, like the Iran hostage crisis—that led to a loss in his bid for re-election. Yet, he did not fade away or give in to bitterness. Instead, he emerged as an elder statesman deeply committed to promoting peace, health, and human rights across the globe. He is hands down the most admired living former president, and he’s admired now on both the left and the right. Because he has managed to transcend the political divide, which is a very difficult thing to do in America today. We see here a reflection of Eli's ethos: a life well-lived is not marked by uninterrupted success but by the willingness to stand by one's principles, to continue contributing positively to the community, and to teach others through one's own experiences of imperfection and resilience. I think there’s a word for this: wisdom. Wisdom is what comes on the other side of failure and disappointment. A perfect person will always be a young fool. But the rest of us have a shot at the true greatness of a wisdom that will be valued by our whole community. And this is Eli’s greatest gift to his people in the end. It is Eli, flawed though he may be, not Samuel, who knows how to listen for God. It is Eli, through failure, through acceptance, and through commitment who knows how to really hear what God is saying. And without Eli to teach him how, Samuel would have never heard God’s call. Wherever we are on life’s long journey, let’s not be afraid to identify with Eli. He is a good mentor for those of us who know what it's like to experience the full spectrum of life's trials and triumphs. Life is not a race to perfection but a pilgrimage through the underworld of our old bones. Remember Eli's wisdom and you might find that your greatest legacy lies in the wisdom you pass on, the lives you touch, and the quiet, indomitable spirit that refuses to give up, teaching us all how to be faithfully imperfect. This morning we’re recognizing and celebrating Epiphany, an ancient Christian feast day, which officially took place yesterday on the 6th. January 6th was Jesus’ original birthday in Christian tradition. Many, many centuries ago, before Christmas, Epiphany was the double celebration of Jesus’ nativity (that’s why the Magi show up) and his baptism (because people believed he was baptized on his 30th birthday). And the baptism at that time was more important than the birthday, actually.

Here in the West today, Epiphany is the end of the 12 days of Christmas, one final stop 0ff at the manger, and in centuries past it was also one last feast, one last party as we left the holidays behind. Some of that celebration still lingers in other countries, but here in the US, Epiphany has never really played a big part in the secular holiday tradition, and January 6th is now unfortunately better known for other things around here. But this morning, I’d like to recommend not January 6th but Epiphany to the celebrations of your house and your heart. What does “Epiphany” mean? Epiphany is an ancient Greek word. It’s translated in the Bible as “appearance” or “brightness,” but that doesn’t do the word justice. Literally, we could translate it as “the shining on,” but the shining on what? Well, Epiphany always means in the Greek the manifestation of a god or a heavenly being on the earth. When Homer in the Iliad or the Odyssey, writes about a god or a goddess showing themselves to a mortal or intervening in some battle or other mortal affair, he doesn’t say “Athena shows up” or “Athena pops by” he says, “Athena shines.” In our scripture reading this morning when Herod secretly calls for the Magi to find out more about the star, he doesn’t ask them when the star first appeared, he asks them when the star first shone. The Epiphany of Christ could be translated as the “Appearance of Christ,” but that translation is boring and incomplete. A better, more poetic, and more personal translation of the Epiphany of Christ is “the Shining of Christ on US”—on YOU. And I think that’s a better way to exit the Christmas season—with a reminder that Christ is shining in the world and shining directly onto you—rather than a hangover on New Year’s Day and then back to work with all kinds of promises to be a better, more productive, more disciplined person. Nothing wrong with a resolution, nothing wrong with a little self-improvement, but Christmas isn’t about you trying harder at life. It’s about what God is doing in your life, it’s about the light of Christ in your life, and how you respond. So, let’s talk about the first responders—the Magi. We usually call them the “Three Wise Men” or the “Three Kings.” Let me blow your mind here: In our scripture reading this morning there’s nothing that says there were three Magi. Could have been two, could have been 12. We don’t know. There’s nothing about them being wise or being kings. And, as was already beautifully demonstrated to us this morning by our three wise women, we don’t even know if they were men! Saying that they were “three wise men” is just more comfortable to Christian tradition than reinforcing the specific reality that Jesus’ first visitors were a bunch of foreign magicians. But there was something special about these pagan magicians—they were able to see what most people couldn’t—the shining of this new star. In our Christmas celebrations, the star of Bethlehem is usually really huge in the sky. You couldn’t miss the thing! And that makes sense because otherwise it wouldn’t make a great decoration. But it’s pretty clear from the scripture reading (and from historical records) that this star wasn’t a supernovae or a comet. It wasn’t some big, obvious sign in the sky that everybody saw. Maybe it was a star that nobody else in the world, but these Magi, had noticed. It must have been small. Maybe it was dim. Maybe in a sky full of bright lights, it was lost in the background. In other words, those Magi must have been paying attention to the light. They must have been looking for it. When Athena appeared in the Iliad, she shone, and then she grabbed Achilles by the hair and she turned him around to look at her. That’s quite an entrance! I wouldn’t mind God showing up like that in my life to be honest. Very direct. Hard to ignore. And it happens here and there. But for the most part our God, our Jesus, doesn’t show up like with a bang to the heroes of the world. Our God shines gently for the whole world to see. And we have some work to do to be able see it. And then after we see it, the journey into the world can begin. Hopefully, you’ve gotten a glimpse of the light this Christmas season. The journey to the manger is over. And now, just like the Magi, we must return to the real world. But the Magi receive one final dream that tells them to go home by another way. Don’t go back the way you came. You’ve seen the light, you’ve followed the light, you’ve received the shining of the baby on you, now you must return to real life on an altered trajectory. Don’t re-enter by the same door you left through. You are transformed, so find a new way forward. Beloved, the Shining of Christ on YOU is not an invitation to a passive admiration; it’s a call to an active transformation. We are meant to be like the Magi: seekers, finders, and then bearers of the light, bearers of good news wherever we go. Yes, the world is filled with conflict, anxiety, violence, greed, sorrow and despair. You see that clearly, of course you do. But you have also seen the light that shines in the darkness. And you know that the darkness shall never overcome it. And that is a faith and a hope that the rest of the world needs to hear from you. We're called to embody the light, to be mini-Epiphanies in a world that has grown accustomed to shadows. In a world obsessed with the fame of “stars,” we’re called to point out the one star that matters most, lost in the light pollution of a hungry, consuming culture. We go back into the world as vessels of the light we have encountered. We’re called to illuminate the dark corners, to warm the cold places, to guide like the Bethlehem star. Don’t hide your light under a bushel. Don’t give up this broken world. God hasn’t given up on it. And God sees us—you and me—as the lamps that will light the way to a new dawn. We must meet injustice with fairness and mercy, pain with healing and compassion, violence with resolve and love. Jesus shines on us and we reflect that light. Shining on others as Jesus shines on us is the true calling of those who have seen and known the light. This is the heart of Epiphany. This is the journey. Beloved, Christmas is ending, but we must shine on. Shine on for the world. Shine on, in service of the one who shines on us. Preaching on: Luke 2:22–40 The Temple was a place you could put your faith in. Imagine it with me: Approaching Jerusalem with Mary and Joseph and the baby, it’s the Temple that you can see from miles off; it’s the Temple that makes up the entirety of the great city’s skyline. Passing through Jerusalem’s walls, in every quarter of the city, wherever you go, the sky is dominated by the Temple’s immensity. Finally arriving at its base, you see great staircases climbing and twisting up three stories before reaching the height of the lowest courtyards. Cunningly carved out of natural features that had been extensively reinforced and expanded upon over centuries, there are—here at the base—carved stones, some 26 feet in length and weighing up to 400 tons—megaliths so large that today science has lost the arts that could have moved them, let alone place and stack them with such exacting precision.

Climbing up to the heights of the walls or the towers of the Temple, 20 stories above the city streets below, you can see an expanse of open architecture that could hold every cathedral, every mosque, every sacred site you have ever visited in the modern world—all of them together—with room to spare. Spread out over the mount, across a space that could hold 27 football fields, you see dozens of buildings and courtyards, bridges and aqueducts, gateways and marketplaces—each with its sacred and civil purposes, leaving room between for up to one million worshipers. You are looking down upon the largest religious construction in all of human history at the height of its glory. And there at the center of the mount: the Temple itself, the Holy of Holies, the place where God dwells, where the Presence of the Lord IS. In the courtyard just outside it, the blood from sacrifices runs over the hewn stones, and the viscera of lambs, and doves, and bulls sizzles on great beds of red hot coals. The greasy smoke climbs up into the sky to delight the heavenly hosts with its pleasing smells. On the journey home, miles away, if you turn your head back over your shoulder you will still be able to see the thin smudge of dark smoke ever rising, reminding you that the heart of the world is still there, beating, pumping lifeblood, touching heaven in its ineffable way, doing the work that is pleasing to God. The Temple is a place you can put your faith in—ancient, huge, and holy, it connects heaven and earth, humanity and God, the beginning of creation and the end of all times. Its walls contain us and protect us. Its weight anchors us. Its smoke tethers us to the Holy of Holies and lifts us up to Heaven. Babies, on the other hand, are the exact opposite sort of thing from temples. They’re brand new—untested and unproven. They are small, fragile, weak, rather useless and, frankly, ill-formed. Their heads are ridiculously big, their limbs are comically short, it takes years just to get them to use the toilet, and then decades more hard work from extended family, friends, church, teachers, doctors, orthodontists, therapists, coaches, and counselors just to get them their first decent paying job and to actually start being productive members of society. Babies? Babies are—cute. Temples… define us. Babies can’t do anything, they come with no guarantees, no return policy, and are really nothing more than—than a possibility. And you do not know what you are going to get. So, I’m not that surprised that in all the Temple that day, filled with tens of thousands of worshipers and visitors, in all that ancient and mighty place, there were only two old souls—Anna and Simeon—who saw the Baby Jesus and who recognized him for what he was—a messianic possibility, a change in the temple tempo, an unfixed future—and who were willing and able to celebrate this uncertain sort of salvation. Of all the pious pilgrims in the Temple that day only Anna and Simeon held the baby in their arms, sang to him, prophesied about him, and thanked God for getting to glimpse the possibility of the Good News, for seeing with their old, dim eyes this small and rather unlikely beginning. What made Anna and Simeon different from the rest? Perhaps, the Holy Spirit was speaking to the whole of the Temple that day, with a spiritual shout to their souls that said, “Come and see! Come and see the anointed one, God’s Messiah, the Christ, who will reconcile the whole world to God! Who will throw open the doors of the Temple! Who will flip the tables of the money changers! WHO WILL DO THINGS DIFFERENTLY!” And maybe a lot of people did, without consciously realizing it, obey the command and wander through the crowds until they brushed past Mary and Joseph, straining intuitively to get a glimpse of God’s salvation, and seeing—where they had hoped to discover another Temple, another Holy of Holies, another old friend, a Messiah entire who breaths fire and knows my name—just a baby, 40 days old. “Ahhhh,” they thought to themselves in the deep chambers of their pondering hearts, “hmmmm... Not quite what I was hoping for. I think I’ll wait and see. A few miracles maybe, some good sermons like the old high priest gives, and of course a strong arm, natural leader, head of a great army, fond of me. When he marches forth with his army from the Temple mount and reaches down to pull me up on the back of his horse, looking deep into my eyes and touching my soul, then I will follow him... to our certain victory. But for now—too risky, too uncertain. Frankly, it looks like he needs me more than I need him! Ha! So, let me go and make my sacrifice and go home again and if this was meant to be, at some point, he will come and find me.” Anna and Simeon were different. Though they had spent their whole lives in the Temple, though in some symbolic way you could say that they were the Temple, they were willing to put their faith and trust in the disruptive possibility—the mere possibility—of something new—of a baby. And now here we are, poised on the threshold of a new year. Are we like the throngs in the Temple, holding tight to the structures we know, only finding solace in the immensity and certainty of the established, the sure thing? Or are we like Anna and Simeon, with eyes that can spy the eternal in the transient—the divine possibility in a humble beginning? What will we put our faith in in 2024? As you look ahead into the new year, if you’re like me you’re probably dreading some things—the war in Gaza, the war in Ukraine, the presidential election. And when you’re dreading big stories like these or perhaps others or possibilities in your own life, the tendency is to feel that only some big miracle, some grand sign or wonder, some total victory can make the world a better place. But those old souls, Anna and Simeon, tell us that there is another way to find a way through difficult times. Are we ready, like those old souls, to embrace the small, the uncertain, the mere possibilities that lie before us? Possibilities that (just like little baby messiahs) might need us right now more than we need them? Will we have the courage to offer our blessings to God’s possibilities? Or will we go home and continue to wait? God’s work is often found in the unexpected: In imperfect people, in small acts of kindness, in quiet moments of prayer. God's presence is not always where we think we should be looking for it. It’s not always locked away, under guard, in the Holy of Holies. Sometimes it's in the hand that reaches out in compassion, in the word spoken in love, in the heart that gives selflessly. Will I give my very best to the little opportunities to make the world a little better in 2024? Or will I go home and wait for the world to settle down and start being nice again? As people of faith, our call this New Year is to watch for the opportunities that God is offering us to have hope and to make things a little better. It's to believe in God's possibilities, even before they've matured, even before we fully understand them. It's to have faith like Anna and Simeon—who knew deep in their hearts that the possibility in a baby was a greater reason to hope than all certainty in the world. The possibilities for this coming year are as limitless as our willingness to hold them and bless them when they’re still just possibilities. Welcome to Advent. Advent began last Sunday, of course, but I wasn’t here because of an attack of the COVID upon my house. I’m testing negative now, but still wearing a mask to comply with CDC recommendations.

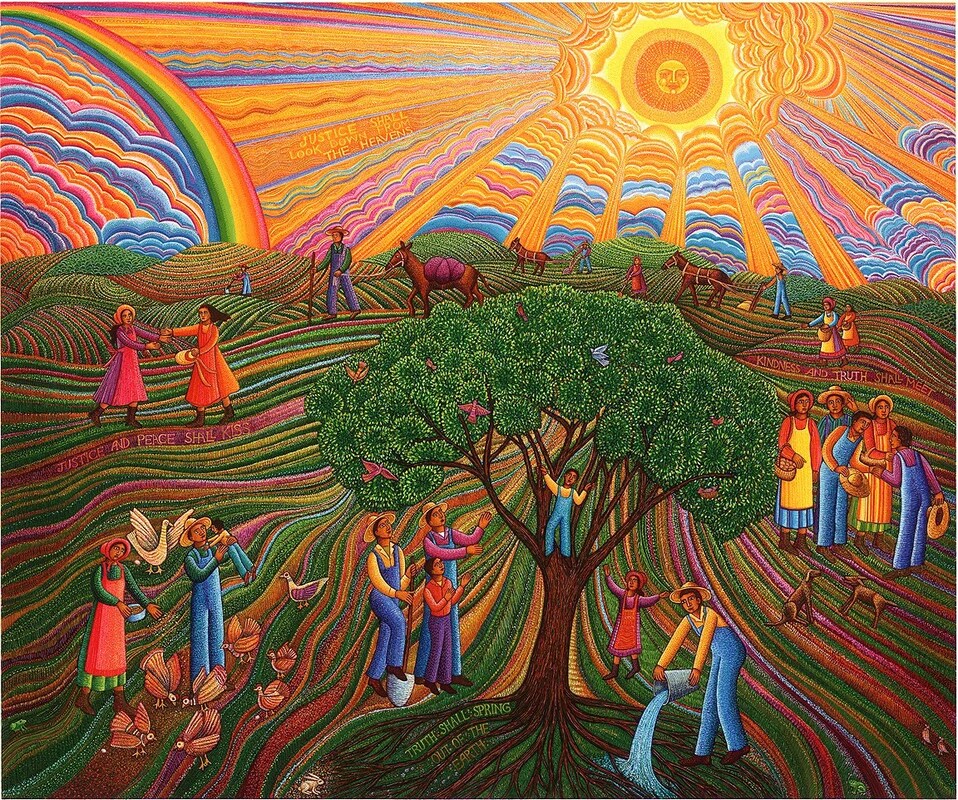

Thank you to everyone who stepped in and stepped up last week to make church happen without me. It’s sort of a wonderful way to begin the new liturgical year—remembering that it takes the gifts of a whole community to worship God every Sunday, not just when I don’t show up. Worship should never be a monologue, it should never be a performance, it should never be consumed. Worship should be as diverse as the community, as robust as the community. Worship requires us. Together, we’re all the resonating chamber of worship. Every one of us is a participant in forming this deep space—the size and the shape of this chamber. And when the Wind of the Spirit blows through us, the music that is produced is produced by all of us. It takes the whole church. I really believe that. So, I account my illness and your readiness to step in and roll with it to be good news for us all on what was the first Sunday of Advent, the first Sunday of this new liturgical year. Advent is my favorite season of the year. Advent is dark. The days are still getting darker. The darkness is getting a little longer each night. The light is still fading from the sky. It’s not Christmas yet. It’s the long, long wait for Christmas. The long, long wait in the dark. It’s not just four Sundays of waiting—Advent stands in for lifetimes of waiting, generations of waiting—for a million, or a billion, or more, long, dark nights of the soul. And at the same time, in Advent, the lights are starting to go up in the night. The tree gets lit in the dark with the tiniest little lights—a twinkling of stars in the darkness. The menorah gets one more candle with each passing night. It’s important to me that we recognize that Christmas doesn’t just happen automatically. Christmas happens because we participate in Advent—all of us, our whole community—we participate. In ancient times, on the night of the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, coming up on the 21st this year, the people would light fires and chant rituals to the sky to ensure that the sun reversed his course, to ensure that he didn’t just diminish forever into the darkness, to ensure that there was a return to the light—that after winter there would be a spring again. As Christians, we recognize that Jesus is the light, the true light that is coming into the world. And it’s tempting to believe that God—being omnipotent, as we’ve been assured he must be, will just take care of everything without us. And yet Jesus came into the world asking us to follow him, to take up our crosses, to participate in the great religious drama of the struggle between day and night, light and shadow, in our world and within ourselves. Worship can’t happen without you. Christmas can’t happen without you. And not everyone will agree with me, but I believe it to be true, that the goodness that God has in mind for this world will not come to pass without our commitment to it, without your participation in God’s plan and Jesus’ way. And I believe that need for you and that participation is best learned in the dark—with the faith and the hope that our participation matters, that it does make a difference. And that’s not easy to feel, is it? Not right now. There are so many reasons to feel depressed and a little hopeless right now. I’m not going to list them all. But I’ll tell you one that’s been particularly on my own mind and heart the last two months—the war between Israel and Hamas: the sickening Hamas terrorist attack of October 7th, the plight of the Israeli and international hostages held in Gaza, the devastating IDF bombings in Gaza, the overwhelming suffering and death of the Palestinians in Gaza, and the disagreement and the moral confusion and the antisemitism and the attacks on Muslims and Palestinians here at home. How can I feel hopeful in the face of such an enduring and divisive and devastating conflict? How can I participate, even in a small way, to help make peace when there is so much virulent and vindictive disagreement about which side to take in this war. People are being persecuted for showing even basic support and compassion to one side or the other. People saying “I stand with Israel” on social media have lost their jobs. People wearing black-and-white Palestinian scarves, keffiyeh, have been shot. Ivy-league presidents have pathetically fumbled basic questions about preventing antisemitism on campus. And at the UN, the US has vetoed the rest of the world’s call for a humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza, because the UN has so far refused to condemn Hamas and the October 7th attacks. So, we’re living in what feels like the worst of all possibilities. Instead of condemning terrorism against Israelis and ending the bombing of Palestinians, we’re suffering a grotesque moral failure of nerve. How do I step into that and actually make a difference? And so we come to the 85th Psalm this morning. The 85th Psalm is a song of restoration. It’s a song sung in a time of darkness, but looking toward the light. It begins by remembering God’s goodness. And it acknowledges that we are living in a time that must be characterized by God’s anger at our failures. And it asks God to intervene again, to show steadfast love, and to return to us again. It is a song that could have been sung on the winter solstice or lighting the candles on a menorah or decorating a tree—God how can we endure this darkness? Return to us again. Return to us again. And then the song turns to hope. The Psalmist turns his eye to what God will surely do for the people. And there are these two wonderful lines of poetry: “Mercy and truth are met together; Righteousness and peace have kissed each other.” When God gets involved with us, and when we act upon God’s involvement with us, it will be possible for truth and mercy to meet one another—it will be possible to condemn terrorism and to call for a humanitarian ceasefire. It’s not one or the other, it’s about finding the way through the dark for the two to meet. Because only if they meet will either of them be possible at all. And true peace will be possible only when it has embraced justice. Peace cannot be made by an occupation or by a wall. Peace requires justice—a redress of the wrongs of the past tempered by the greater hope for the future. And justice will be possible when it has kissed peace. Justice cannot be made by revenge. Justice cannot be made by doing to the other what has been done to you. It can only be achieved by doing to the other what you would have them do to you. Peace must accept that it is too weak to stand on its own. Justice must accept that without mercy and forgiveness it will ravage the world anew. It’s not one or the other, it’s about finding the way through the dark for the two to embrace. Because only if peace and justice kiss one another will either of them be possible at all. Our job as Jesus’ followers is to keep God’s vision clearly in our minds and hearts—mercy and truth, righteousness and peace. In a time of war and division, we are called upon to do what we can to enact that vision without exacerbating the conflict. If we throw up our hands in despair or overwhelm or fear, God’s vision will fail. Where do mercy and truth meet? Where do righteousness and peace kiss? In us! In our hearts and lives, in our communities and in our world. God has sown the seeds for peace and justice in us and the question is, what kind of soil will we be? The Thursday before last, the Montclair Interfaith Clergy Association and the Montclair African-American Clergy Association held “A Sacred Space for Lament and Love During a Time of War” at the UU church in Montclair. We as local clergy got together in October and November and knew that we needed to do something to enact our values here in our community. If we didn’t take a stand of love and support for everyone—of truth and mercy, justice and peace—we knew that greater conflict and even violence might erupt in our own community. And we knew the only way we could achieve such a space—such a resonating chamber—was by including the participation of everybody. And so local rabbis spoke, and a local imam. A Palestinian-American woman spoke. And an Israeli-American woman spoke. Each spoke their truth in turn. And after each person spoke their truth, all of us in attendance—about 100 diverse community members—said together to that person, “We hear you, and we love you.” It was not an end to war or to conflict. It was not the dawning on that great morning we all hope and long for. But it was a beginning. And it was profound. It was an utterance of truth and mercy, of righteousness and peace, spoken from the depths of the darkness, calling the light back into the world. There is a lot of disagreement about the best way to be a Christian. Wars have been fought over it. People have burned at the stake. We’ve excommunicated one another and broken away from one another. You might imagine that the causes of such violence and discord had to be of the utmost importance, but many of our disagreements are almost too silly to even say out loud: How much water is required for baptism? Was Jesus 50% human and 50% God or 100% human and 100% God? That sort of silly stuff—questions Jesus himself was never concerned with.

How many sermons did Jesus ever preach on the proper way to baptize someone—let alone how much water to use? Baptism is an encounter with the living God—it’s meant to be an experience. That’s where the focus should be: What is being experienced? That’s what churches exist for—to help people have an experience of God! But for many churches the experience of God has gotten lost behind very banal rules and disagreements over, for example, the quantity of water being administered at baptism. This process of creating and enforcing a nitpicky orthodoxy is the way that churches kill Christianity—it’s how we turn a living, relevant religion into a bunch of stupid, misdirected rules and “beliefs” that have absolutely nothing to do with Jesus and nothing to do with faith. And so many people today, in this liberal era where you have choices about how you spend your Sunday morning, many people today are not coming to church. How many people do you know who tell you that they don’t come to church because they experience God more out in nature on a hike on Sunday morning? And us church people, we sort of roll our eyes at things like this. But what if we took them seriously? If you think about it, of course they feel that way, because out on a hike there is only experience; there are no irrelevant rules about how and what you’re supposed to be experiencing. In order for a church like ours to break through the burden of history in which many churches have alienated spiritual people through nitpicky orthodoxy and to break through the cultural malaise making people feel that church can only be irrelevant to their life and to their experience of God, a church like ours needs to focus its energy on the direct experience of God without arbitrary rules about what is and isn’t appropriate in an encounter with God. And in our scripture reading this morning, Jesus shows us the way. I believe that a church that prioritizes feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, clothing the naked, healing the sick, and visiting the prisoners is a church that is prioritizing the experience of God and minimizing the baloney. And Jesus says it right there. This is how you get to know me. Because as you serve and live with those in need, you serve and you live with me. In my own life, I heard the call to ministry at 16-years old. I went to Boston University and studied religion academically, hoping that that would sort of scratch the itch and I wouldn’t actually have to go through with becoming a minister because I wasn’t all that excited about serving in a church because I had also felt the lack of focus on the experience of God in church. Studying religion academically didn’t quite do it, unfortunately. I found myself just more and more fascinated by all the ways in which people experience God and what the experience of God can do to a life—it can totally transform it, it brings meaning and purpose and satisfaction. So, after graduation, still trying to get myself out of ministry, instead of going to seminary, I decided to go to Miami. I joined Americorps and ended up working as an on-site volunteer coordinator for Habitat for Humanity of Greater Miami. And do you think it worked? Do you think I got out of my Christian faith in Miami? No, because again, as I was running away from church, I ran directly into the arms of Christian experience! Let me explain: Down in Miami, I sometimes went to a liberal Presbyterian church I liked on Sunday. But mostly, and unexpectedly, I found God among the rafters and frames and people of the Habitat houses. Every day was a day of work for God’s people—giving families and children a home. I began to understand my work building houses as essentially Christian work, as a Christian experience, and I found my understanding of God’s love growing more than it ever had before. I didn’t just love the neighborhoods I worked in and the families I worked for—I also worked in and for them out of my love for them. I began to understand that love is an action, not a feeling. We should measure our faith not by what we believe in or not, but by the actions we take and the relationships we build and the difference we make. If we want to really attract people into our church, we need to prioritize the experience of God. I’m not saying that we don’t do this at all. But I think we have an opportunity to grow in our experience of God which will create an opportunity to grow as a congregation. Jesus’ words this morning: Feed the hungry, welcome the stranger, clothe the naked, heal the sick, visit the prisoners serves as the bottom line of what it means to be a Christian. Are you a sheep or are you a goat? In the end, Jesus says it all comes down to this—our willingness feed, to welcome, to clothe, to heal, to visit. The activities are not irrelevant—they are the foundation of our faith, a cornerstone of how we experience God. If we make these core activities a core part of our mission and identity, then people who desire a Christian experience of knowing Jesus, won’t think of our church as irrelevant—they will know that at a minimum they will be called upon to act out the love of God in the world. That’s not disconnected from people’s lives, that’s about deepening the connection to your life, that’s about finding real meaning, it’s about living a living faith. My experience is that if you’re feeling disconnected from God or from faith, all you need to do is look to the needs of the people who are closest to you. Right here in our neighborhoods, in our area, there is a need for new relationships to solve old problems. And if we’re willing to do that, our lives will be full of meaning, full of connections, and full of love. I think we’re a nice-Jesus kind of church. I know that I’m a nice-Jesus kind of preacher. Man, do I struggle when Jesus says something like this: “For to all those who have more will be given, but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away.” That doesn’t sound very nice.

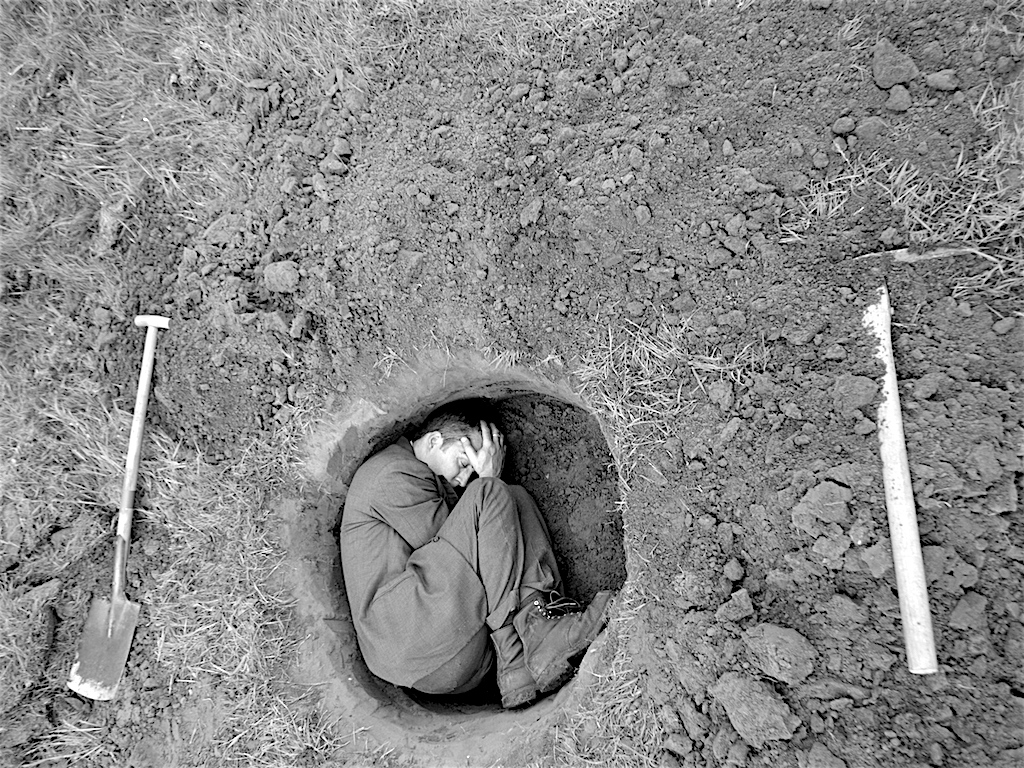

I love it when Jesus says, “So, the last will be first and the first will be last.” That’s my Jesus—turning the powers of this world unexpectedly upside down! And Jesus just said that five chapters ago in Matthew. I preached a great sermon about it. No problem! But now here Jesus is saying what? Instead of the third slave with the least moving to the front of the line, his talent is taken away from him and given to the first slave who already has the most?! This is the exact opposite of the last will be first! This is the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, right? Something’s got to be going on here. We’re not the only ones who are confused here. Plenty of Christians have been uncomfortable with this particular parable in Matthew right from the very beginning of the faith. In other gospels, the gospel writers try to make us feel less sympathy for the third slave. Luke says the third slave stores the money improperly—he doesn’t bury it to keep it safe as was the accepted cultural practice at the time. He’s careless with it. So, that explains the harsh judgment. In the Gospel of the Nazoreans, the third slave spends the money on wine and loose women, so obviously when the master throws that criminal in prison, it feels like justice—it completely contradicts the parable of the prodigal son, but it’s something anyway. Because when it comes to this poor guy in Matthew’s gospel, I feel terrible for him. He wasn’t irresponsible. He wasn’t wicked. He was just afraid. He had the least of anybody, and he didn’t want to risk it. He was cautious, scared. Haven’t you ever been scared? I’ve been scared. And sometimes it’s sidelined me too… Last week I told you all about “hitting rock bottom” in my early twenties. Basically, I was running away from my call to ministry because I was intimidated by it. Basically, I was scared. I was afraid of failure because there are a bunch of scary things about being a minister. You have to do it all. You have to write and preach a sermon every single week for like the rest of your life. You have to always do and say the right things. You have to offer care to people in crisis, and make sure the grass has been cut properly, all while thinking of the big picture and having a plan for the future of the church, all at the same time, all while managing conflict and disappointment and disagreement, all while practicing healthy boundaries and finding balance and being spiritually healthy, and doing it all in a way that makes it look easy and inspires people. It basically feels (from the outside looking in) that you have to be perfect. And I knew then (and still do) that I ain’t perfect. My fear of my own life, led to a strong feeling of being unfulfilled, which led to depression and a spiritual hole in my life, which led to self-medicating and ultimately unhealthy behavior, which led me to one of those rock-bottom moments where you look in the mirror and you barely recognize the person you see reflected back at you. All because I was scared. All because I thought that the potential for failure was just too risky. Why did I think that? Why did I think that the potential for failure was such a terrible thing to risk? An interesting thing about this parable is that it gives us no information about the hypothetical slave who got maybe three talents and went out and put them work, took risks, did his best, but through no real fault of his own cleverness and willingness to do business, ended up failing—ended up losing the money. What would the master have done to him? Well, we don’t know. Which is interesting. In this parable, failure is surprisingly not really an option. You either risk and succeed or you get scared, and you don’t try at all. Risking and failing is not something that this parable wants us to worry about. That’s our fear talking. And when we let that fear overcome us, that’s when we end up at rock bottom—in the outer darkness. It’s not failure we need to fear. As FDR famously said from the depth of the Great Depression, “All we have to fear is fear itself.” Now the story of how I went from rock bottom to the near-perfect superstar pastor standing before you today is just too long and involved a story for any one sermon, but it began with the realization that any risk, any failure was better than sitting myself out of my own life in the outer darkness that I had damned myself to out of fear of playing the game of life. If I’m being honest, I wasn’t just afraid of failure. I was in some unconscious way afraid of God. Maybe this is why I feel so much sympathy for the third slave. It’s not failure he’s afraid of, it’s the master he’s afraid of. He says it directly: “Master, I knew you were a harsh man, so I was afraid.” “Oh, you believe, I’m harsh?” says the master. “Then I will judge you according to your own faith.” It was my faith, my fear, that landed me in the self-exile of rock-bottom outer darkness. It wasn’t a damning, judgmental God up in Heaven looking down his nose at me. It was God within me. I faced the judgment that I most feared to face because I allowed my fear to rule my reality. I can’t tell the whole story, but the turn around moment for me began with this simple act—I allowed myself to pray a fearless prayer to God. I don’t remember exactly what I said but it was something like, “God, I want to risk everything for you, I don’t want to play it safe, I want to give you everything I’ve got, I want to make a difference in the world even though I’m scared. I know you’ve got my back, I know you’re calling me, I know you have a plan, I know it won’t be easy, and I believe that if I live my life well that even if I fail I cannot fail. Take away my fear and show me the way.” And once I prayed that prayer, everything changed. I opened the door just a crack and God came rushing through. And I was suddenly on the fast-track to seminary. Now, since those miraculous days I have failed many times. I have messed up, missed the boat, fallen short. Many times. I’ve beaten myself up for these things at times, but I have never again known the outer darkness that I was in when I buried myself out of fear instead of trying out of faith. Now, today is Consecration Sunday—in just a moment we’re going to turn our pledge cards in with our weekly offering and we’re going to bless them. Now, often this parable from Matthew gets interpreted through a Stewardship lens. We think this is a parable about investment, self-improvement, personal responsibility. But I don’t think that’s quite right. It’s about fear. And so my hope is that whatever number is on your pledge card today, that you turn it in fearlessly, in the presence of our God who wants nothing more than to welcome you into the joy of the kingdom of heaven. Whatever may come in 2024, I know that we can’t fail as long as we’re willing to be church together. Preaching on: Matthew 25:1–13 I think we’re a nice-Jesus kind of church. I know that I’m a nice-Jesus kind of preacher. I love those stories in the gospels when Jesus throws the doors open wide to everybody, when he heals, when he sits downs and eats with the sinners and the tax collectors, when he forgives, when he teaches us to love everybody. That’s my Jesus.

But you can’t be nice all the time, can you? It doesn’t work out. If you’re always nice, if there’s never a boundary, if there are never any consequences, eventually you’re going to get taken advantage of, right? We all struggle with this. Parents! We want our kids to know that we’ll always accept them for who they are no matter what and that we’ll always love them. And most of us figure out that as the primary and unconditional source of love and acceptance in their lives, we are also in the best position to tell them, “NO! No way! No, you will not jump off the roof. Yes, you have to go to school.” And, in fact, if we don’t do this for them, we’ll do our kids a great disservice. We model for them what their own internal reasoning and morality should eventually look like—we help it to grow in the right direction. That requires sunshine and water and fertilizer and, when things get really hairy, it requires the pruning shears. So even a nice-Jesus preacher like me has got to take Jesus seriously when he says “mean stuff.” Just think about what happens with our kids: “No, you can’t have another cookie.” “You’re the meanest dada in the world! I don’t like you! I’m not gonna be your friend anymore!” Geez, kid, give me the benefit of the doubt. Could you just for a minute imagine that I still have your best interests at heart even though I’m saying NO? So, let’s give Jesus the benefit of the doubt this morning. Remember, Christianity is not a religion of total acceptance. It’s a religion of total acceptance and radical transformation. When you hit rock bottom, it’s good to know that you’re accepted just as you are, but you don’t want to stay down there forever, do you? Accepted or not, it’s good to know that there’s a way back up. But sometimes the way back up begins with the door slamming shut in your face, right? That’s what rock bottom is. It doesn’t feel like a feast of acceptance. It’s a transformative coming up short. A radical and undeniable NO from the very depths of your being. And, sometimes, we need that. When I was in my early twenties, I moved out to San Francisco. I moved out there to work in theater, because I loved theater, but also to run away from my calling to ministry, which I found very intimidating. And life got messy really quick because I was depressed, and anxious, and unfulfilled, and I didn’t know what to do about it, so I was doing everything I could do to avoid the fact that I was avoiding life. And when you’re behaving like this, bad things happen. I had a wonderful girlfriend who I moved to California with. I messed that up royally by being totally emotionally unavailable. She ended our relationship rather spectacularly, which left me devastated and emotionally and physically homeless. I wasn’t taking care of my health. I was drinking and smoking and eating at Chili’s every single day. I became really bitter and angry. I started partying with my coworkers after work. And nobody parties better than theater folk! Anything to fill the spiritual hole inside of me. One night after too much fun, I realized I had done too much damage to myself to even be able to drive down the street, let alone all the way home. So, I climbed into the back of my pickup truck, and I passed out. I was parked out in front of the bars, so I could hear everybody laughing at me as they walked home—pretty humiliating. At some point it started raining. I wake up in the morning sick and wet and it’s time for me to be back at work. So, I drag myself inside the theater and I go in the bathroom and try to clean myself up. And I look in the mirror. And you can imagine what I must look like. And as I looked at that sin-sick, bedraggled reflection in the mirror, I heard a voice in my head, but a voice bubbling up from the deepest chamber of my heart. And it said to me, “I don’t even recognize you. Who are you? Truly, I tell you, I don’t know you.” Boom! Rock bottom. The door was slammed shut in my face. And thank God! Thank God! Because that moment was the beginning of me turning it around. I think one of the problems we run into here is that we think of Jesus as some judgmental guy up in heaven somewhere damning us to hell with the flick of his wrist for some very human mistake. But was the voice that I heard when I looked in that mirror an external, judgmental voice? No! No way! It was an internal, loving voice. The voice of someone who loves me so much, he was willing to say NO. He was willing to tell me the truth that I had been running away from. Jesus is not just some guy up in heaven, right? He is also the Christ-child born within me, the logos, the Word which was in the beginning with God, the ordering principle of love through which everything which is made is made. If God is everywhere, then God is also within me and within you. We are never just damned from the outside. We’re guided lovingly from within by a voice and power that is bigger than us. Now, why did I hit rock bottom? Well, in part, it was because I was running on fumes. I had no gas in the tank. Or to use a more ancient metaphor: I had no oil in my lamp. I was a foolish young woman. And this is the other place where this story feels a little mean. When the foolish young women ask the wise young women if they can spare a little oil, the wise young women say NO. Now, this doesn’t feel like a loving parent saying no. This feels more like sibling rivalry. It feels mean and stingy. Doesn’t God want us to share with others? Doesn’t Jesus teach us to be generous and charitable with those in need? And who could be more in need at this moment that these young women with no oil so close to being swallowed by the darkness? But this parable isn’t about external social relations. This parable is about something inside of us. And so the metaphor kind of breaks down here. If I’ve mistreated myself and run out of gas and I’m about to break down, I can’t just borrow $20 bucks from someone to get a couple gallons to get me home. It doesn’t work that way. Nobody else can give you oil from their lamp. It doesn’t work. The oil you burn to be a true light to the world is an oil that must come from within. You can’t get it from anybody else. You have to do the work yourself. It’s your work. It’s your life. Now, there are lots of people who will promise you that they can give it to you. And whatever spiritual snake oil they sell you may even get the engine going for a little while, but ultimately, it’s not going to work. The oil you burn to be a true light to the world must be your oil—oil you have made with your life. The wise can’t give to you. The merchants can’t sell it to you. It comes from God inside of you. So even a nice-Jesus preacher like me has got to take Jesus seriously when he says “mean stuff.” Because sometimes we need that voice of wisdom and discernment, guiding us from within, to set us back on the right path. If you have no oil in your lamp, if you have become acquainted with the rock at the very bottom of life, you've got to do the hard work of getting back on the right path. But if you are fortunate enough to have oil in your lamp, here's what Jesus might say to you, you wise young women: Share your light generously. Allow it to spill over into the lives of others through acts of service, words of encouragement, shoulders to cry on. Let it light up the lives of others through generous giving to your church this stewardship season. Remember, next Sunday is Consecration Sunday, when we turn in our 2024 pledge cards for a blessing. You can’t give oil to anybody else. But you can burn your oil to make light for others. When someone else is down, and your light touches them in the darkness, and helps them to find their feet again, you’ve changed that life for the better. That’s what a church is in a lot of ways. It’s a place where the people with oil in their lamps make light for the people who are running on fumes. And when the time comes that we’re on empty, we can trust that others will be there to help light the way home. And the brighter that light shines, the greater the impact of our ministries and our work together. The oil in our lamps may come from within, but the light shines outwards, illuminating the world around us with compassion. So, let’s tend the lamp within, trimming the wick, replenishing the oil, and together let’s keep the lights on at Glen Ridge Congregational Church. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed