|

The story goes that someone once asked a rabbi why it was that in the old days God used to show right up and speak to people and be seen by them, but nowadays nobody ever sees God anymore. The rabbi replied: “Nowadays there is no longer anybody who can bow low enough” (related by Carl Jung in Man and His Symbols).

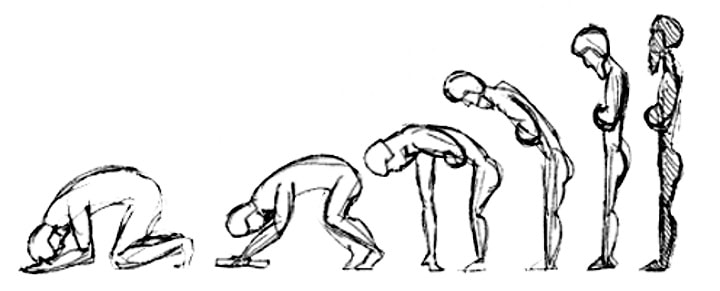

This morning, the first Sunday of Lent, I want to talk to you about humility—about the possibility of bowing low enough. If not bowing low enough to see God like in the old days, then at least bowing low enough to see and to hear a little more of the truth. And what is the truth? At least bowing low enough to see one another. Because seeing one another and hearing the truth that comes from another person’s mouth, another person’s experience that is different than ours, is not easy. To encounter the truth that is bigger than ourselves requires a spiritual shift in perspective. I’ve been thinking a lot about what that shift in perspective is—about how to describe it. And I know that at least part of the answer, part of the low bow to God and to our neighbors, is the cultivation of the virtue of humility. The first thing we need to discuss in a little more detail is humility’s public relations problem. Just like any virtue, if practiced without intention, and without awareness of context, and without concern as to its effects on the practitioner or upon others, then humility can be transformed from a virtue into a tragic character flaw—a deadly sin. It is possible to believe that we’re being humble when really we are being dangerously self-deprecatory or docile in the face God’s will. Our prayer of confession this morning put it nicely (Marlene Kropf, Congregational and Ministerial Leadership, Mennonite Church USA): I pour out my sins of pride, unbending, unyielding arrogance, self-righteous zeal for perfection, damning judgements, vicious grasp of my own destiny. AND… I pour out my sins of refusal to take my place, cowering fear, spineless accommodation, failure to speak, unwillingness to be counted. We also have to remember that in this country for hundreds of years, much of what was preached as the supposed Gospel of Jesus Christ was, in fact, nothing but slaveholder religion—a moral abomination and a Christian heresy that told Black people held in the bonds of slavery that they should be meek and humble and compliant and accept the yoke and the rod of slavery as God’s good intention for them. And that sentiment is still in the system, it’s still out there, it’s still preached. The context and the language have been updated, but we haven’t completely exorcised slaveholder religion from American culture or from American Christianity. And so we must be careful about who recommends humility to whom and to what ends. Similarly, women in our churches have always been expected to display the virtues of humility more than men. For thousands of years, we have asked women to step back, to quiet down, and to cover up. When they have complained about their oppression or their abuse, the Church has often told them that this is their cross to bear—with the grace and humility appropriate for their sex. And so we must be careful about who recommends humility to whom and to what ends. Humility can be thought of as a kind of submission, but it must always be a submission to love, a submission to righteousness, a submission to justice, to fairness, and to equity, and never to their opposites. When we are truly humble, others may laugh at us, others may jeer at us, others may disrespect or even attack us, but true humility leaves us empowered and in control—we are humble, we are never humiliated. The Black and White protesters who sat in at lunch counters throughout the South to protest segregation were howled at and beaten. They had food dumped over their heads, they had cigarettes put out on their arms. They were called vile names. They didn’t fight back physically. They let that hatred break on them like a storm on the rocks. And then the police came and hauled them off to jail. When in court they were given a choice of paying a fine or spending a month or more in jail, most of the protesters took jail—not because they couldn’t afford to pay, but because they wanted to show the powers that be that they could withstand the worst that the system could throw at them. The segregationists told Black people to stay humble and to accept their place. Instead, the Civil Rights Movement used true humility to throw the mighty down from their thrones—because sometimes heaven shall not wait. Just as a false sense of superiority is not humility, neither is a false sense of inferiority. True humility is about finding the real sense of who you are, who God created you to be—not too big, not too small. One of our Lenten themes this year is “Lent of Liberation: Confronting the Legacy of American Slavery.” I’m reading a Lenten devotional by that name and you all are invited to join with me in reading and discussing the text this Lent. As I’ve been reading and preparing myself for Lent and reading about the struggle for racial justice and even just the conversation around racial justice—how we talk about race and racial justice, I feel like our greatest challenge to seeing, believing, and acting on the truth is our limited perspective—a truly human problem, built right into our essential nature: None of us knows it all. That right there is reason for humility. Instead, what we see is that if the truth is convenient to us, we accept it. Because you don’t ever have to bow to a convenient truth. You don’t ever have to bow to a convenient religion, to an expedient morality, a cheap grace, an easy God. But when the truth is complicated and difficult to understand or when the truth convicts us or feels uncomfortable to our opinions of ourselves or our lifestyle, we don’t wanna bow. And much of the time, we may not even be aware of the mental and moral gymnastics we’re performing in order to keep our backs straight and our knees unbent. If only we could see as God sees! But Psalm 139 tells us that “such knowledge is too wonderful for me; it is so high that I cannot attain it.” And we can never attain it by going high. The only way available to us for getting closer to God’s perspective is to go low—to take the Lenten path, to bow a little deeper, to make a practice of humility. The Psalm concludes, “Search me, know my heart, test me, know my thoughts. I won’t try to hide from you anymore because you know me completely and I’m going to stop pretending that you don’t—even my sin, even my wickedness, I’m going to give it to you, so that you can lead me in the way.” You can only sing those lines from a downcast position. To sing them and to mean them requires the lowest kind of bowing down there is—the surrender of the soul to grace and to love. It is not the position of the know-it-all, not the position of the authority, not the position of someone who has locked onto the perspective of their own ego to the exclusion of all competing perspectives. Someone once asked Jesus, “What is the greatest commandment?” Jesus said love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind. And a second is like it: Love your neighbor as you love yourself. And a second is like it. These are not two arbitrary and unrelated commandments. They are deeply connected. So, if you are going to bow low to God’s perspective, you also have to bow low enough to hear your neighbor’s perspective. Wait. What about the flat earthers? What about Qanon? What about neo-Nazis? Am I really supposed to bow down to their conspiracy theories and lies? No! Absolutely not. In the documentary John Lewis: Good Trouble, Lewis tells us that when civil rights protesters went out to perform non-violent civil disobedience, it was his intention to “look my attacker in the eyes.” We’re not bowing down to anyone’s opinions or to their hatred, we’re bowing low to the Image of God within them. Our neighbors are not always right. In fact, a little time on your neighborhood Facebook group will prove to you that your neighbors all disagree. We do not bow low enough to hear our neighbors’ perspectives because they are right, we bow low enough to listen to our neighbors because that is a part of loving our neighbors. I do not bow low enough to hear my neighbors’ perspectives because they are always right, I bow low enough to hear the perspective of others because I am not always right. In Jesus’ parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man we see the consequences of being too high and lofty to bend our ear to the experience of another person. I can imagine that the rich man had all sorts of excuses for remaining comfortable with Lazarus lying at his gate and suffering. We continue to hear these excuses today—sometimes they come out of our own mouths: “Well, Lazarus he must have taken a wrong turn in his life to have ended up like that. He must have done something to deserve it. He must have gotten himself addicted. He must not have worked hard enough. I bet he makes a lot of money sitting there and begging all day. Not to mention how much we give in taxes to clean up after problems like him. And you don’t get sores like that all over your body unless you’re not careful—I can’t be blamed for his “lifestyle choice.” And haven’t I worked hard for everything I’ve got? Don’t I deserve to enjoy it? Shouldn’t I be able to take a break and not have to worry about people like Lazarus?” We’ve all had judgmental and haughty thoughts like this that accounted ourselves too high and other people too low. And Jesus tells us in the parable that when we aren’t serious enough about the absolutely necessary spiritual practice of bowing low enough to hear the perspective of another, we fix a great chasm between ourselves and others that is impossible to cross. Those of us who have privilege—and many of us do, whether it be male privilege, or straight privilege, or white privilege, or the privilege of economic status or educational degree or citizenship—those of us who have privilege ought to pay close attention to the fate of the rich man. Lazarus was already humble. It was the rich man who needed to learn to bow. But he didn’t. So, this Lent I recommend to you a practice of an empowering humility. We have tried recently to solve our problems in this country with arrogance, with bitter fighting, and without consideration of any kind for our neighbors. Many of our fellow citizens are committed to that path. But it is a path to hell and destruction for ourselves and our neighbors. We cannot force anyone off that path they’ve chosen. Abraham says it clearly, “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.” My responsibility lies with me. I can choose to step off the path of destruction. I can choose to listen with empathy and compassion to my neighbors even when their truth makes me feel uncomfortable. I can choose to emulate the humility and strength of John Lewis, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr. I can choose to bow lower than I have ever bowed before.

0 Comments

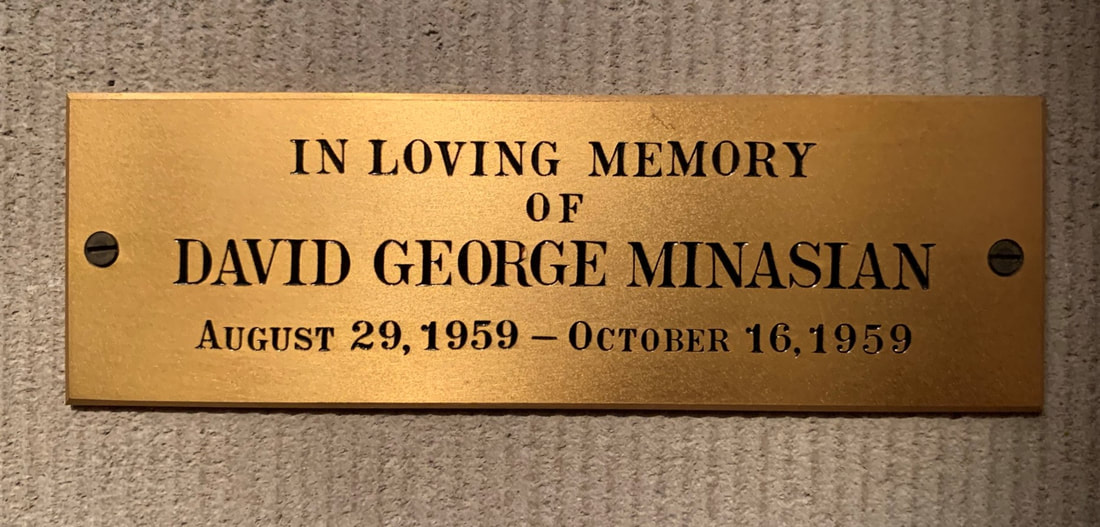

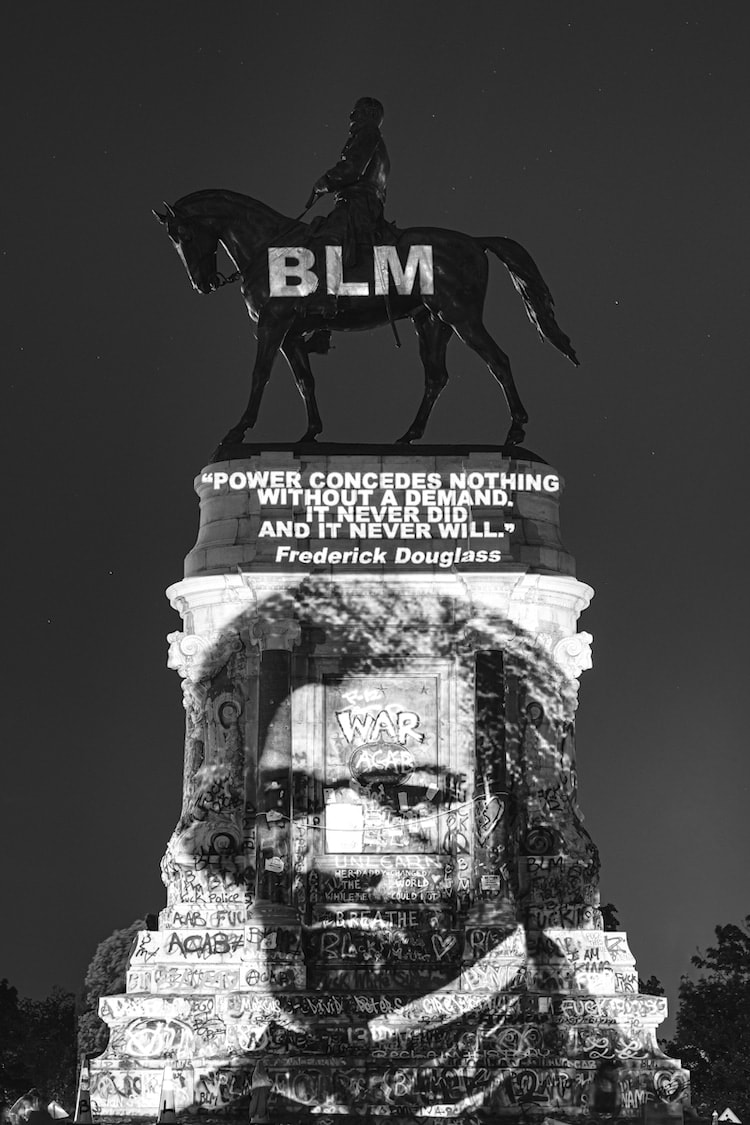

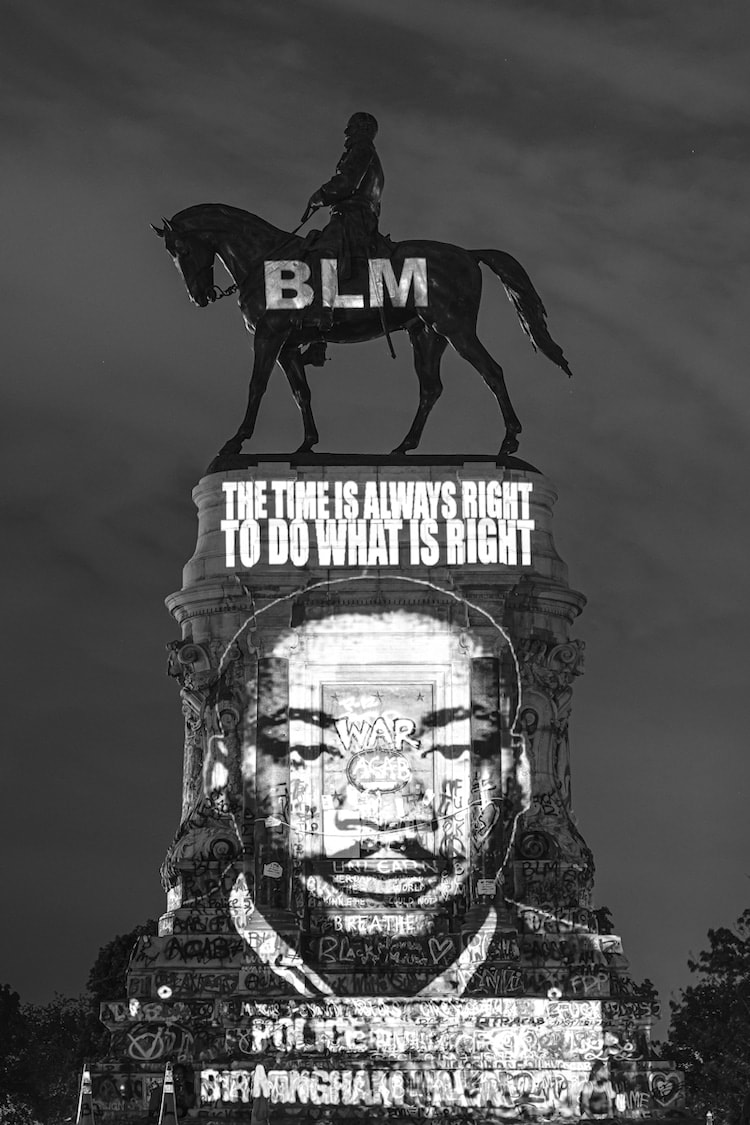

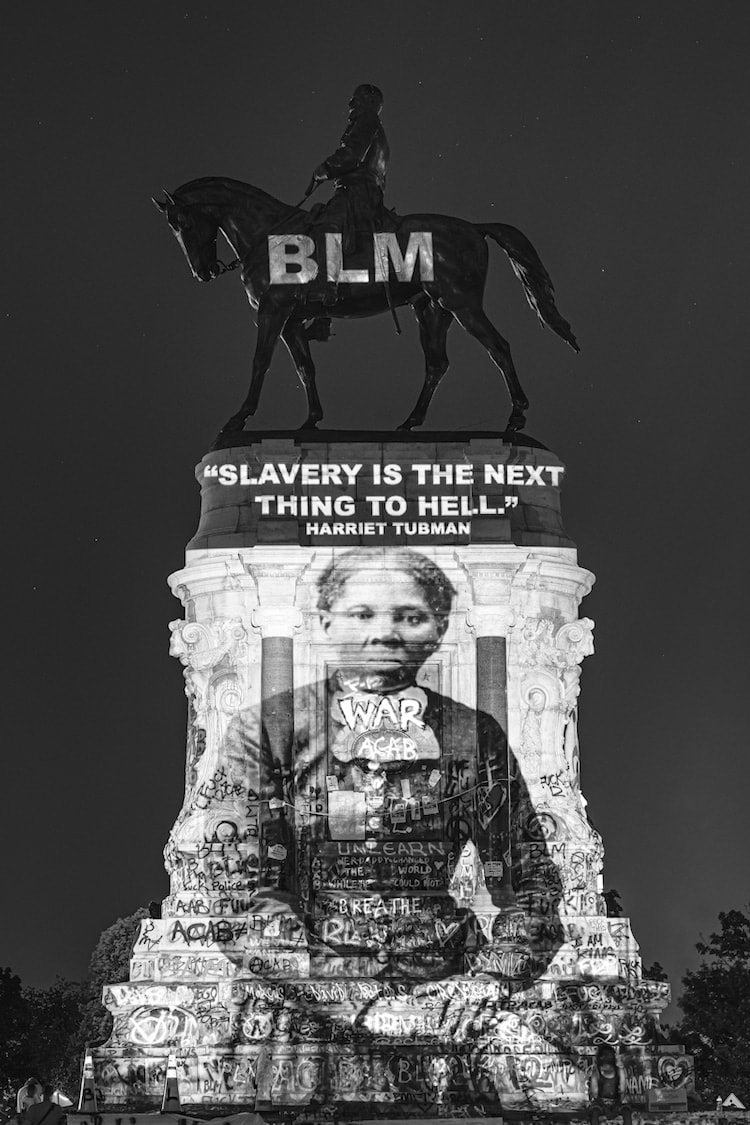

Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” So God created humankind in God’s image, in the image of God, God created them; male and female God created them. —Genesis 1:26–27 (NRSV, alt.) Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain apart, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no one on earth could bleach them. And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who were talking with Jesus. Then Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi, it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” He did not know what to say, for they were terrified. Then a cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud there came a voice, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” Suddenly when they looked around, they saw no one with them any more, but only Jesus. As they were coming down the mountain, he ordered them to tell no one about what they had seen, until after the Child of Humanity had risen from the dead. —Mark 9:2–9 (NRSV, alt.) In my sermon this morning I’m going to be talking about racism and transfiguration. And I’m indebted in my thinking here to a former Minister of Racial Justice for the United Church of Christ, Rev. Elizabeth Leung. I couldn’t have gotten to this place without her work. So, thank you, Rev. Leung for your ministry. OK, I’m gonna start you off with a quick Sunday School lesson this morning, just to lay the foundation down for you. Then we’re going to climb a mountain to see what we can see and to see who we might be. Then I’m going to tell you why I’m over here on this side of the chancel at the lectern instead of standing over there at the pulpit like I usually do—I know you’re all dying to know why: stay tuned to find out! OK, Sunday school first! Gather ‘round little ones: Genesis tells us that we human beings have all been created in the Image of God. What does that mean exactly—created in the Image of God? Does that mean that God has thumbs, just like me? A bellybutton too? A spleen, perhaps? Aside from the unfortunate fact that the patriarchy has still got many of us pretty convinced that God is a man, we’ve mostly understood for a good long time that God isn’t like us like that—in physical form. It’s other things—language, morality, consciousness, love, creativity—these are the ways we’re created in the Image of God. God doesn’t look like us! But, still, somehow, we still look like God. There is still something sacred about the physical human image in all of its created diversity—because God created humanity to be physical and to be diverse. And I believe that our physical diversity of sex, gender, sexual orientation, race, body shapes, sizes, and abilities is a part of our creation, a part of our humanity, and therefore a part of our reflection of the Image of God. So, it’s not just morality and creativity and language that make us reflections of God’s Image. It’s also our diversity. And diversity joined together through the bonds of loving relationships is called community. Human beings were created to be in beloved community together. That’s part of what it means to be human. That’s part of what it means to be God. After all, doesn’t God say, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness”? When your species reflects God, you don’t look like just one thing because God contains multitudes. God talks to herself. God is everything. So here’s the Sunday School lesson for Racial Justice Sunday: Because we are created in God’s image and because it is in our very diversity that humanity most fully reflects God’s Image, racism is not only a sinful human system of devaluing, oppressing, and exploiting people based on the color of their skin, racism is also a disfigurement or a disfiguration of the Image of God inherent in Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color. Someone once asked Jesus, “What is the greatest commandment?” Jesus said love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind. And a second is like it: Love your neighbor as you love yourself. And a second is like it. These are not two arbitrary and unrelated commandments. They are deeply connected because if you hate your neighbor, if you oppress your neighbor, if you devalue your neighbor, you are desecrating and disfiguring the very Image of God that you claim to love. This is all stuff we should have learned in Sunday School: God doesn’t have thumbs (and isn’t an old white man with a beard), but we still look like God (all of us) because we human beings are thinking, loving, and beautifully diverse. Racism is an evil that infects the way we think, infects the way we love, and infects the way we live together. It’s a sin against God and a sin against our neighbors. It is a systemic social disease in effect, but it is a systemic spiritual disease in origin: It is a disfigurement of that which is most human—God’s Image. Racism is a disfigurement of that which is most human—God’s Image. That make sense? OK, Sunday School lesson is over. Now, we’re going to go out for a little Sunday hike. We’re going to hike up a mountain with Jesus, and Peter, James, and John. We climb and we climb and we climb, and when we get to the top, we look out over the world and Jesus is transfigured: He’s shining with light, his clothes are brighter than any white fabric we’ve ever seen, he’s talking with the spirits of Moses and Elijah, and we hear the voice of God. Jesus’ human form which had always reflected God’s Image is now radiating God’s Image. Jesus’ body has become like the burning bush—God is literally shining and speaking through him. Instead of a disfiguration of God’s image, Jesus’ shows us what transfiguration looks like—that transfiguration is possible. We learned in Sunday School, of course, that Jesus is fully human and fully God at the same time. The mistake we make when we climb the mountain is that we assume that Jesus’ transfiguration is a part of him being fully God. But I think the transfiguration is about being fully human—as God intended us to be. When the burning bush appeared to Moses, was that particular bush chosen because it was fully God? No, it was simply fully bush—transfigured by the energy of God, burning but not consumed. We live in a racist society. All of us in this society are witnessing a disfiguration of the Image of God all around us that dehumanizes all of us and that limits our ability to participate in God’s fire, God’s light, God’s energy. The Apostle Peter warns his readers that participation in sinful ways can block us from “becom[ing] participants of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:3–4).To correct this disfiguration of God's image within us we need a culture-wide Transfiguration towards what Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called the Beloved Community—a diverse, antiracist society ruled by justice and love. We, the Church, are the Body of Christ. And if Christ’s body was transfigured on the mountaintop, then this Body of Christ can be transfigured too. Like Paul wrote in 2 Corinthians, “All of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transfigured into the same image. ”God gave us God’s own image. We have disfigured that image. And through Jesus, we can transfigure it too. The more we become fully, justly, lovingly, diversely human, the closer we come to the one who made us so. OK, very good, would you please tell us now why you’re standing over there. It’s driving me crazy. All right! I’m at the lectern this morning because I want us to imagine what the first steps of transfiguration could look like in our church. And, so, I wanted to preach with this piece of artwork behind me. I’ll let you take a closer look—buckle up! Just take a look. What do you see? Who do you see? Who do you not see? I see Jesus sitting on a little hill of sorts. And he almost looks like the transfigured Jesus. His clothes are perfectly white. And he’s surrounded by light. This isn’t the transfiguration though, it’s a representation of Jesus allowing the little children to come to him after the disciples tried to chase them off. What you can’t see on screen is that there’s a plaque underneath this painting that says, “In loving memory of David George Minasian, August 29, 1959–October 16, 1959.” The Minasian family was a very prominent family in our congregation and community. For 110 years we’ve been giving out the annual Minasian Bible Award to an outstanding Christian educator in our congregation. And the stained-glass window “Righteousness, Truth, & Beauty” was donated by the Minasian family. And one of the Minasians was a mayor of Glen Ridge in the 1940s. Little David Minasian was less than two months old when he died in 1959. I can’t imagine the pain of his mother and father, his brothers and sisters, his grandparents as they sat in these pews in their grief. I hope I never know pain like that. And I am so glad that they had a church that let them paint their grief and their hope and their love on the wall of the sanctuary. Amen to that. All that being said, we must also observe the painfully obvious: that everyone in this picture is white. It is a reflection no doubt of its time and culture, and we must remember it was the time and culture of segregation and Jim Crow in this country. We see that Jesus is depicted as a white person of European descent. Of course, we all know that Jesus was not white. Jesus had no European ancestry. He was a brown-skinned, Middle-Eastern Jew. Now cultures all across the world have tended to depict Jesus in their own image. But in our culture, which has so often preferred and uplifted the image and form of white people while denigrating and disrespecting the images and forms of people of color, is it justifiable to continue to entertain the comfortable fantasy of white people that Jesus was white? There are 16 children in the painting, they are all white—every last one. And I mean really white. These kids have not been to the beach lately. And I have no doubt that in 1959 that was an accurate reflection of the demographics of this congregation. But God be praised that is no longer the case. We are Black, we are South Asian and East Asian, we are Middle Eastern and Cuban and Brazilian and mixed race and bi-racial and more. If you were a child of color looking at this image at the front of your church, what would it say to you? I think it would say to me: You have no place in God’s Image. That is a racist message that cannot be ignored or allowed to stand unchallenged in this congregation. It must be transfigured. How do we do that? I don’t know! We’re going to need to think about that together, and I hope we do because there is an opportunity here for us—an opportunity to see God more clearly. Now, you all know that we’re in the midst of a culture war over one kind of “art” in particular—confederate statues. There are a lot of people who want them taken down because of the pain of having to see an individual who fought for the cause of slavery glorified in public art. And in some places, the powers that be are taking them down. And in others, the powers that be are leaving them up. And in some places the people are organizing to tear them down without sanction or permission as a form of protest. I’ve never been a big fan of the Confederates, personally. I never routed for that team. And I agree that there is no place for confederate statuary in our public commons. I don’t mourn them being taken down or torn down at all. But then in Richmond, VA there is a 12-ton, 60-foot-tall statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The crowd who tore down the other confederate statues in town couldn’t budge this one. And its ultimate fate is tied up in appeal in the courts. And then something incredible happened. After the murder of George Floyd last year, this statue of Lee was transfigured by an artist named Dustin Klein. So much so that now a statue of the quintessential confederate general has become an emblem of the Black Lives Matter movement and the area around the statue has become a gathering space for the movement and the wider community. Let me show you a few pictures of this transfiguration: With our picture of white Jesus welcoming the white children we could decide to take it down from the wall. We could decide to cover it up somehow. And we could decide to transfigure it in some good way. But what we can’t do is we can’t ignore it or dismiss it—that would be a missed opportunity and a disfiguration of God’s Image.

And obviously we’re not just talking about this because we only just need to transfigure one painting. We’re talking about this as a concrete example of how we can begin to transfigure ourselves, our church, and our wider community. We want to see God more clearly. We want to be truly diverse. We want to participate in God’s divine energy. We want to be an antiracist congregation; we want to be a part of the great work of our time—of ending racism and solving these deep structural problems with love and justice. So, let’s end with Jesus’ own prayer for us. At the close of the last supper Jesus prayed to God, “The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one.” They went to Capernaum; and when the sabbath came, he entered the synagogue and taught. They were astounded at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes. Just then there was in their synagogue a man with an unclean spirit, and he cried out, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the Holy One of God.” But Jesus rebuked him, saying, “Be silent, and come out of him!” And the unclean spirit, convulsing him and crying with a loud voice, came out of him. They were all amazed, and they kept on asking one another, “What is this? A new teaching—with authority! He commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him.” At once his fame began to spread throughout the surrounding region of Galilee. --Mark 1:21–28 (NRSV) When I heard that someone named Amanda Gorman was going to read a poem at the inauguration, I didn’t have any real expectations. I don’t think many of us did—one way or the other. I’d heard briefly on NPR that a 22-year-old named Amanda Gorman was going to be the youngest ever inaugural poet, and that’s all I knew about her. On stage with big names like Biden, Harris, Brooks, Gaga; Gorman faded into the background a bit.

But then the day came, right? And Amanda Gorman (a self-described “skinny black girl, descended from slaves, raised by a single mother”) stepped up to the podium to perform her poem, The Hill We Climb, and she basically stole the show. She stepped up to the mic and claimed her authority with everything she was—with her bright yellow jacket and her bright red hair band, with her voice, with her performance, with her perfectly chosen words which were finely crafted to uplift and to challenge a complicated nation at a troubled time. When Jesus entered the synagogue, no one had ever heard of him before either. And then he stood up to teach and the people were astounded by his words because he taught like he had authority (and not like one of the scribes). We have a lot of questions about this authority: Where’d it come from? What was it like? What explains it? Maybe the experience of sitting in that synagogue watching Jesus stand up to teach felt something like watching Amanda Gorman become the breakout star of the inauguration. Where did her authority come from? I watched an interview that Gorman gave to Anderson Cooper after the inauguration. She talked about overcoming a speech impediment as a child. And she told Cooper that to prepare for writing her poem she first read every other inaugural poem, in order to steep herself in the tradition and the power of the words that came before her. And before she stepped up to that mic, she closed her eyes and she said to herself this invocation, “I am the daughter of black writers who are descended from freedom fighters who broke their chains and changed the world. They call me.” Later when Gorman was on The Late Late Show with James Corden and she told him that she felt like the experience of the inauguration was “beyond her” and that her poem was really a moment for everybody. So, where does Amanda Gorman’s authority come from? It comes from the words of all the inaugural poets who came before her living within her intersecting with the black writers and freedom fighters who gave rise to her still living within her intersecting with her rising to the challenge of adversity and overcoming impediment intersecting with her answering a call to a moment that she recognizes was greater than herself. Her authority comes from the fact that she has integrated these traditions and this history and this spiritual orientation within herself. And we were able to hear with own ears how they fused within her person and came out of her mouth with power. I think about Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. whose day we celebrated right after the inauguration. Who in all of American history had more authority than King? Who in all of Christian history had more authority than King? Few, if any. King who was discriminated against, threatened, beaten, and jailed countless times. His authority was not handed down to him from the powers that be. According to them he had none. He had to claim his authority from within and from on high. It was an authority of spiritual integration, moral principle, and life-or-death struggle. Inside the person of Rev. Dr. King, great, old traditions came together: the traditions of the Hebrew prophets who had visions, who dreamed dreams, and who provoked the powers of this world; the tradition of the Black experience in the United States and the traditions of the Black church; the traditions of Thoreau’s civil disobedience and Gandhi’s non-violence resistance; the traditions of freedom and liberty—the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, and, most importantly, the promise of the American Dream. King didn’t teach church history like a historian. He didn’t lecture on the Constitution like a professor in a law school. He didn’t preach about the prophets like someone who believed that God long ago had stopped speaking. Those are more like the traditions of the scribes. And it’s very important to remember that we need the scribes—we need the scribes to keep the great traditions alive. But we don’t need the scribes to try to protect us from the next great tradition that is rising up from them. The next great tradition that will rise up will rise up when someone like King, when someone like Gorman integrates the great traditions and teachings within themself and then goes beyond them all to give the world a new teaching. Jesus, like King, like Gorman, was not merely an imitator or a preserver of the old ways. He was a devoted student of all the great traditions of his people—the law, the prophets, the culture, the debates, the schools and the schisms, God’s covenant and the people’s great hopes—all those traditions lived within him. He integrated them into himself. They were his strong and honored foundation. And Jesus honored them so much and so passionately that he couldn’t contain them from going where they wanted to go. And he himself couldn’t be contained by them. Instead, he was liberated by them—they were pushing him to go. So, Jesus became an innovator, a catalyst, a preacher of possibility and authority. Amanda Gorman says she believes in the power of words so it seems like we should take a closer look at the word “authority.” It’s a fine translation from the Greek, but it’s interesting to look at the etymology of the Greek word—how it would have sounded to the Greek listener. This word “authority” came from another Greek word we often translate as “lawful.” “Is it lawful to do this? Is it lawful to do that?” is usually how it’s used. The problem is that the word we translate as “lawful” has no connection to the Greek word for “law.” Instead, “lawful” comes from an even more basic Greek word meaning just “to be.” So, another more literal way to translate the word we translate as “lawful” would be to say, “Are we able to do this? Is it possible to do that?” And then that means another way to translate “authority” would be to say, “For he taught them as one having potency, as one having possibleness, as one unconstrained. And then we realize, that’s what this authority of Jesus that Mark is talking about really is. It’s the authority to get unstuck. It’s the authority to exorcise the demons—to chase the old specters out of the room, and stir up a fresh spirit. The authority to teach something truly new. It’s funny that Mark doesn’t bother to tell us what Jesus was teaching. We’ll get to some of Jesus’ core teachings later in Mark’s Gospel. But for right now, all Mark wants us to see is that Jesus is an innovator and not an imitator, a leader and not a follower. One way to say it is that Jesus has authority. Another way to say it is that Jesus is challenging authority. And we see that truth with King and also with Gorman as well. Jesus will challenge the authority of the synagogue and religious institutions, he will challenge the assumptions of the people, and he will even challenge the power of the spirits and the demons. And in his willingness to challenge the authorities and the complacencies of the world, Jesus claims his own authority and offers us the truest and greatest comfort of all—the possibility of new way. What we’re talking about here—what Jesus is modeling for us—and that’s so important, I think, that we don’t think of Jesus’ authority being like the authority of a superbeing or a God-man and totally unattainable to us. Jesus is showing us the way here. What he’s showing us, and what we also see in people like King and Gorman is simply spiritual growth. Or what Carl Jung (the great psychologist and psychoanalyst) called “individuation”: the process of coming to understand, of giving voice to, and integrating or harmonizing the various components that make us up so that we can become our true self. Beloved, what greater authority is there than that—to be your true self? We’re going to be talking a lot about “growth” together as a church over the course of 2021. And I think it’s important to take some of these lessons forward with us into those conversations. First, a strict imitator cannot grow. Because true growth must be oriented to the realization of your true self. And you cannot imitate your way into your true self. Now, I’m not knocking imitation or preservation or tradition. Imitation can build us a strong foundation. But if we get stuck on strict imitation, we can get ourselves stuck to a relatively small piece of ground while the greatness of all the sky is calling us to grow up. The process of spiritual growth is a process of getting unstuck—not totally dislodged, not falling off the wagon—but growing into the liberty of possibility. This authority of Jesus is just what happens when you grow from a strong foundation toward the unique purpose that God created you for. Second, growth is not a numbers game, right? When we talk about growing as a church, we’re not talking about butts in pews, views on videos, or dollars in the offering plate. Do we want our fame to spread throughout the surrounding region like Jesus’ did? Sure, we do! But growth is not a numbers game, it’s a spiritual orientation. If we want our fame to spread throughout all the region, we need to discover within our congregation how to put all the layers of our identity and tradition and history together in a way that is true to us and which will draw other people to us through the revitalization of our authority. And third, growth cannot happen without facing adversity and conflict. It might not be as imposing as racism to a black leader, or a speech impediment to a spoken-word poet, or a demon in the synagogue, but adversity and conflict are a part of every life, and in every church, and within every person or community that is trying to grow and define themselves. If we don’t face the adversity or the challenge, that means that right then, right there, we’re stuck. We’re no longer moving. We’re no longer growing. And our authority dissolves into avoidance, our voice retreats into silence. What sometimes happens in churches undertaking a process of spiritual growth and rediscovery of authority is that some people are made a bit uncomfortable. And we’re understandably afraid of the possible conflict. We’re afraid of hurting feelings, of causing someone to feel unwelcome, of causing someone else to lose their temper, of losing members, of pledges going unpaid. And these are things to be concerned about, right? We don’t want to be mean or reckless. But working through this kind of conflict is the price we must pay to be ourselves! To have a voice! To be a community that has a point of view and values we’re willing to stand up for! To discover our authority—and to grow. Beloved, I know that we have a voice. I know that we are relevant to our community and our neighbors. I know we’re not afraid of adversity and that we don’t get paralyzed by conflict. I know that we have a faith, and traditions, and art and music, and a welcome that provide us with a strong foundation. And I know that we are ready to grow. As Amanda Gorman says in The Hill We Climb: When day comes we step out of the shade, aflame and unafraid, the new dawn blooms as we free it For there is always light, if only we’re brave enough to see it. If only we’re brave enough to be it. Amen. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed