|

Preaching on: Genesis 45:1–15 Last week we heard the story of the inciting incident of Joseph’s life: Joseph, a young, favored dreamer, is resented by his older brothers, who attack him and sell him into slavery in Egypt. This week, obviously, the lectionary has skipped ahead to the final resolution of that day. Here we are, years later, and Joseph is Pharoah’s governor, one of the most powerful men in the world. Using his dream powers, he’s saved Egypt from a great famine. His family is also suffering this famine in Canaan, and they run out of food. So, Joseph’s father sends the same ten older brothers who attacked Joseph to Egypt to seek aid for their family.

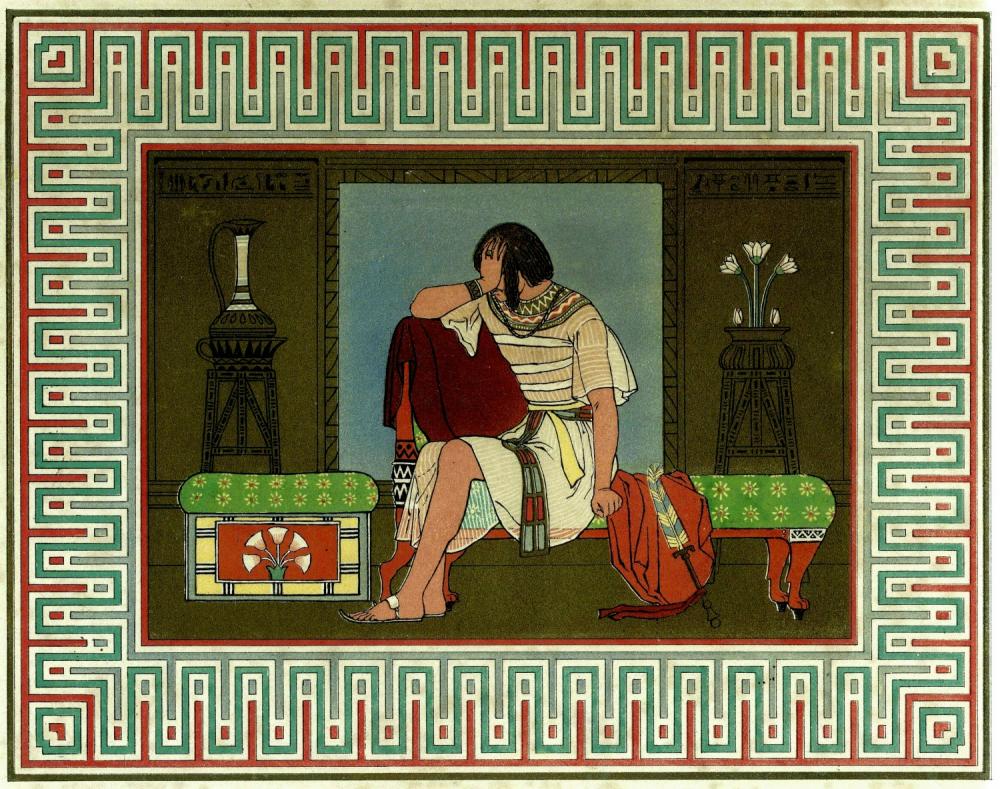

Our scripture reading this morning is “the big reveal.” Joseph has decided to reveal himself to his brothers and to offer them forgiveness and reconciliation. It’s a beautiful scene. And, of course, the lectionary has a limited number of Sundays to tell the story, and the editors wanted to “get to the good part.” And what’s the good part for a good, obedient Christian? Well, it’s the part where forgiveness is practiced, right? But I think the lectionary actually skips over the really good part. The lectionary assumes, from a Christian perspective, that forgiveness is the most important part of the story, and its natural conclusion. As if someone had commanded Joseph—or even advised him—to forgive his brothers, as Jesus has commanded us to forgive. But no one ever did that for Joseph. In fact, read the entire book of Genesis. There is not one single word in there about anyone forgiving anyone else under any circumstances. There’s one story about God considering forgiving some people, but then he destroys their city anyway. Forgiveness is not a virtue—it’s barely a concept—in the book of Genesis. Joseph has never heard the sermon on the Sermon on the Mount. Joseph has never read the Bible. He’s never even been to synagogue. None of that exists yet. And so how does Joseph come to this moment of forgiveness? The real story here is what comes in the chapters between the arrival of Joseph’s brothers in Egypt and this moment when Joseph finally reveals himself. The time between the brothers’ arrival in Egypt and our reading this morning could have been up to two years long. It was at least many months long. And Joseph goes kind of crazy. When his brothers first show up in Egypt, Joseph recognizes them, he knows exactly who they are. But he accuses them of being spies. He knows they’re not. But he’s in a sort of shock. He doesn’t know what to do. He throws them into prison. Then he decides to release them back home with food, but he’ll keep one of them hostage. And he’ll only release the hostage brother if the other brothers return with his little brother, Benjamin. But how does he even tell them he wants Benjamin without revealing himself? It’s a convoluted mess! How is this going to work? What’s he up to exactly? Is this revenge? Is this reconciliation? All that’s clear is that Joseph is in crisis. Now, not knowing that Joseph can understand them (he’s been using an interpreter to speak to them), the brothers speak right in front of Joseph about how all this is happening to them because of what they did to Joseph, and he has to leave the room to weep. A wonderful image, captured on the bulletin cover this morning, of Joseph in the heart of great personal struggle. So, after they pay for their grain, Joseph sneaks the money back into his brothers’ grain sacks, which seems like a kindness, but is actually a curse because now his brothers fear the Egyptians are going to think they’re thieves. His brothers return some months later after much conflict at home, with Benjamin, and there’s a whole another round of tricks. The brothers think they’ll be in trouble for the money, instead they’re given a feast by Joseph. All this time still not knowing it’s him. And Joseph again has to get up from the table to leave and weep. Now another trick: This time, Joseph puts his silver chalice in Benjamin’s sack and sends his guards after the brothers who drag the brothers back to Joseph as thieves trembling and afraid. Joseph tells them he’s going to have to keep Benjamin with him as a prisoner. But one of his brothers begs he be taken instead for the sake of their father who loves Benjamin most of all. And it is only at this point that Joseph can’t take it any longer and he reveals himself to his brothers. It’s becoming clearer now what’s been going on here. His brothers’ arrival has put Joseph into a moral crisis. What’s he supposed to do? He could kill them all and nobody would bat an eye. You know, revenge. Or better yet—justice! Why not? Joseph wouldn’t be murdering them, he’d be executing them, as is his right as governor. Or an eye for eye—just make them all his slaves. But how would that affect his father; how would it affect his younger brother? Joseph is a dreamer and surely his father told him about his own dream when God came to him and made him a promise about his family becoming a great nation. And what about Joseph’s own dreams? He dreamed twice of his family bowing down before him. Those two dreams affected him so much, he told them to his family, searching for an answer to them. They touched something deep inside of him. Those dreams were maligned and misinterpreted by his brothers as being nothing more than a desire for power and domination over them. But Joseph never felt that way—the dreams touched something deep within him—a desire to be more than he could even understand at that time. Do you see that this is the real story? This is Joseph’s great moral struggle. Not to forgive or punish. Not justice or reconciliation. That’s all there, but that’s not the heart of the matter. Joseph is asking himself over the course of these months of crisis: Will I stick to the call of my dreams to allow my life to be bigger than me—bigger than I have ever yet imagined it to be? Or will I succumb to the petty cruelty of my brothers’ way of seeing the world? Will I exact my revenge and thereby fulfill their interpretation of my dreams, and doom myself to being nothing more than a rich and powerful man? As Christians, we’ve been taught that we’re supposed to forgive. We don’t think it’s easy. We know it’s hard. But we think that it’s supposed to be easy. Like what we should all be striving for is to be such a saintly person that forgiveness is just no problem anymore. You just do it because it’s required. And so knowing that we’re not saints, we think that forgiveness and other great spiritual works are beyond us and we don’t try or we go through the motions, but we don’t really get all the way there. But when we think like this and act like this, we miss the whole point. The whole point is that forgiveness is hard. Forgiveness is so hard that to even contemplate it puts us—just like Joseph—into moral crisis. To get out of the moral crisis we have two choices: Give up or struggle forward. When we choose to struggle, to suffer this great moral crisis and not to run away, that is where the magic happens—that is where we discover that our lives can be bigger than us, bigger than we ever imagined. That is where God’s dreams for us can come true. In the struggle about what to do about his brothers, as Joseph kind of goes crazy and is doing all these weird and contradictory things, Joseph’s life is lifted up. Do you see that? The struggle is so hard that Joseph begins to realize that the meaning and purpose of his life is bigger than him, bigger than his goals, his desires, his justice. It is dreams which must define him—dreams which have always belonged to God. When Joseph realizes his best possible life is bigger than him, that’s when he can forgive. But he can only realize that inside of a great moral crisis and by struggling through it to discover a resolution which is beyond him. Joseph puts it into words like this, “It was not you who sent me here but God.” One of the most powerful lines in the Bible if—IF—you understand the struggle that got him there. If you think, “That’s just what we’re required to say—that everything is a part of God’s plan,” it falls terribly flat. You get mad at God for that. You did this to me? You start thinking what kind of a rotten God does something like that to a person? Because you’re not experiencing what Joseph is experiencing. In that moment, Joseph has stepped beyond himself and his own life. He is bigger now than he ever thought possible. This is not passive obedience to some difficult or distasteful article of faith. This is struggling with everything you have to resolve an impossible crisis and to discover in that great work that God has provided us with the dream and that grace to succeed in ways that will change everything. Beloved, Joseph's story shows us that the path of forgiveness and reconciliation is not easy or straightforward. Don’t forgive simply to follow some rule. In fact, when you encounter any great difficulty in life or in faith, don’t seek the easy way out. Take the winding road filled with moral struggle and crisis. When we open our hearts to God's great purpose in our lives, we will find the strength to travel that road. We are bigger than our wounds. Our lives are part of a greater story. May we have the courage of Joseph to step into the struggle. May we have the strength to stick with this agonizing inner work. May we have the faith to see that our lives are more than we imagine. God has a dream for us.

0 Comments

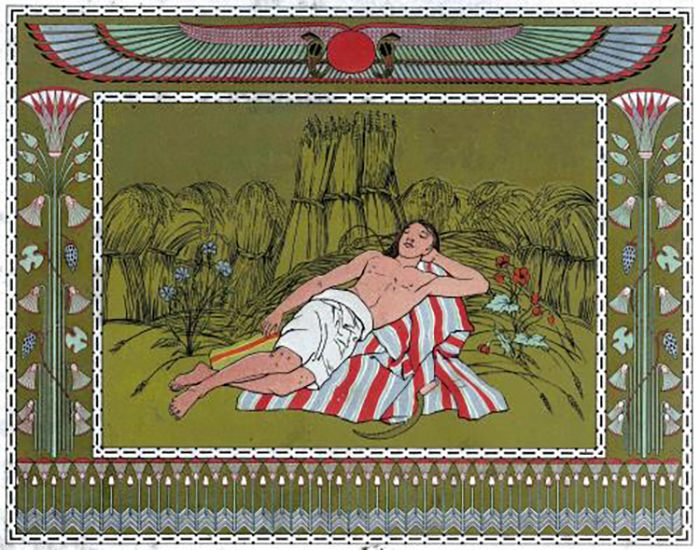

Preaching on: Genesis 37:1–28 Joseph is young. Joseph is favored by his father (Jacob now also known as Israel). He wears outlandish clothes for a shepherd. But worst of all, Joseph is a dreamer. And this is the crime that his brothers can’t forgive him for. And so they decide together to squash the dreamer.

Why? Why’d they do it? Now, the story seems to offer us a lot of little reasons, right? Joseph is different, he’s daddy’s favorite, our mom didn’t like his mom, he’s a tattletale… but ultimately it all comes down to his dreams. “Here comes this dreamer,” they say to one another. “Come now, let us kill him…and we shall see what becomes of his dreams.” It’s the dream, as much as the dreamer that threatens them. Squash the dreamer, they think, and you can squash the dream. In our world today, we might say, “It was just a dream,” right? A dream is just the accidental experience of your brain processing the previous day’s data, we might say. That’s one really good way to squash the dream, typically modern—basically, dreams don’t even exist, stupid. But that option isn’t available to Joseph’s brothers. They know the power of dreams, but they don’t trust that power. Because they can’t control it, they don’t have it, and they fear the power of the person who does. Our translation this morning reads, “Here comes this dreamer…” but another way to translate it is, “Here comes the master of dreams.” Squash the dreamer, and maybe you can squash the very power of dreams. And once you’ve exiled that visionary, forward-looking power out of your life, then (hopefully) you’re back in control of things. But Joseph’s story tells us that the exact opposite is true. To the brothers, it seems like Joseph thinks he special, and he’s dreaming of his own greatness, at their expense. They think that Joseph wants to dominate them. In fact, (because most of us know the story of Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat) we know that Joseph’s dream is actually calling him to spare his brothers, to forgive and serve them, and to save his family after he becomes Pharoah’s highest-ranking commander and his brothers come to Egypt in search of food during a devastating famine. But none of them, not even Joseph, understand the dream yet. They’ve got a vision, but they don’t have the message yet. So often, we want the message first. We want the business plan, first. And then from that sober message, we can draw out a vision, a dream, to add a little pop to our presentation. But that’s not how it works. The dream comes to us from we don’t know where. We’re not in control of it. It’s bigger than us. It comes from God. Maybe we hear the dream from that weird guy in the weird robe who doesn’t act like everybody else. And so his brothers conspire to squash the dreamer. At first, they want to kill Joseph. But they can’t quite do it. That’s a truth about dreams. You can kill a dreamer, but you can’t kill the dream. The dream is way bigger than the dreamer. So, they imprison him and then they exile Joseph into slavery to Egypt. But again, we know it doesn’t work. And that’s another truth about dreams. A dream can’t be “cast out.” A dream can only be “brought forth.” Jesus, in the Gospel of Thomas, famously says, “If you bring forth what is within you, what is within you will save you. If you don’t bring forth what is in you, it will destroy you.” Joseph is his family’s vision. He is the visionary of the Israelites. In fact, in the Quran, when Joseph’s brothers tell their father that Joseph is dead, he weeps so hard that he goes blind. And I think we could also think of Joseph as a symbol of the vision of the Church. Do we have a dream? Do we have a vision of the future that we’re bringing forth? If the answer is maybe, kind of, not really, not sure, or if the answer is a backwards looking answer, rather a forward-looking answer—a vision for the future, then the story of Joseph and his brothers has some strong warnings for us. The Israelites’ dreamer—their visionary, their artist, their imaginal connection to God’s plan, Joseph—becomes the enslaved dream interpreter of a foreign power. Joseph doesn’t dream in Egypt, he interprets the dreams of Pharoah. And rather than being the visionary leader of his family, Joseph becomes an administrator for the vision of Egypt. The power of the dream is always going to land somewhere. The Church can lead with vision, or all the other great powers of the world will pick off our young visionaries and make them administrators of their dreams. This also happens to us as individuals. You can follow your dreams, or you can work for the dreams of others. For most of us this is a compromise in life, but no matter what we do to pay the bills, we should hold on to our own vision for ourselves. So my question for you this morning, beloved, is, Do you have a dream? Is our church a landing place for God’s vision for the future? Or are we a place that squashers the dreamers? I think we have a dream here. And we’re in the beginning phases of articulating it. And we’re maybe a little shy, we’re a little worried about rocking the boat too much, sticking our necks out too far. And we worry about wrapping everything up with a pretty bow, we worry about making a case that’s unsinkable. And that’s wise, of course. But it’s also wise to remember that before the interpretation comes the dream. All of us need to make space within ourselves and space for others to have an imperfect, not yet fully understood, kinda weird dream. That’s the way forward, I think. Start with a dream and don’t rush to a perfect plan. Follow the dream. It is bigger than you. It is bigger than our plans. Speaking of supporting the young dreamers of the church. I’m really happy that later this afternoon, we’re holding a final interview for the position of Youth Ministry Coordinator. The YMC will be coordinating jr. high and sr. high youth group activities for five local churches. How’s that going to work? I honestly don’t know all the details. But we’ve got five churches and a wonderful candidate for the job who are simply willing to follow the dream of having programming for our young people. I have no idea what we’ll have a year from now. But we and four other churches are going to follow the dream into the future. Of course, we’ll all fondly remember the youth groups of the past. And I’m sure many of you have all kinds of stories and advice to share. And we need that as we follow this dream to wherever it leads, and as we do everything we can to support the dreams and the faith formation of our young people. Why couldn’t Joseph’s brothers support his dream, follow it to whatever conclusion it was going to come to naturally without trying to kill it? Ultimately, they fell into a trap that we often fall into too, which is to believe that the dream serves the dreamer. It’s so strange that we think that because dreams are often a real pain for the dreamer. They were for Joseph. They were for MLK. They were for Gandhi. They were for Philip K. Dick, and for Jesus, and for so many other dreamers and visionaries, who suffer greatly for having and sharing dreams. In fact, the true dream rarely serves the dreamer. Instead, it serves the community. It’s a calling—a calling not just to the future but to the service of others in that future. So may we be a community that makes space for dreams. May we be willing to follow dreams even when we don't fully understand where they’ll lead us. May we nurture the young dreamers among us, knowing that their visions are gifts for all of us. The future belongs to the dreamers. Our job is to listen, to make room, and to walk faithfully with them. The dreamers show us the way forward. They connect us to God's vision. Beloved, don’t let anyone take that away from you—from us. The dream is so much bigger than we can see. The story of Jacob wrestling with someone—we’ll talk more about who he’s wrestling with in a bit—it’s one of the most iconic stories in all of scripture. There are lots of strange things that go on in the Bible. Sometimes we find ourselves scratching our heads, other times we just shrug our shoulders and move on, but every once in a while you get a story like this—a story where even if it were the only story in the whole Bible that had survived to this day, it would be every bit as mysterious and powerful. It would still captivate our imaginations. This morning I’ll talk a little bit about why this story works on us the way it does.

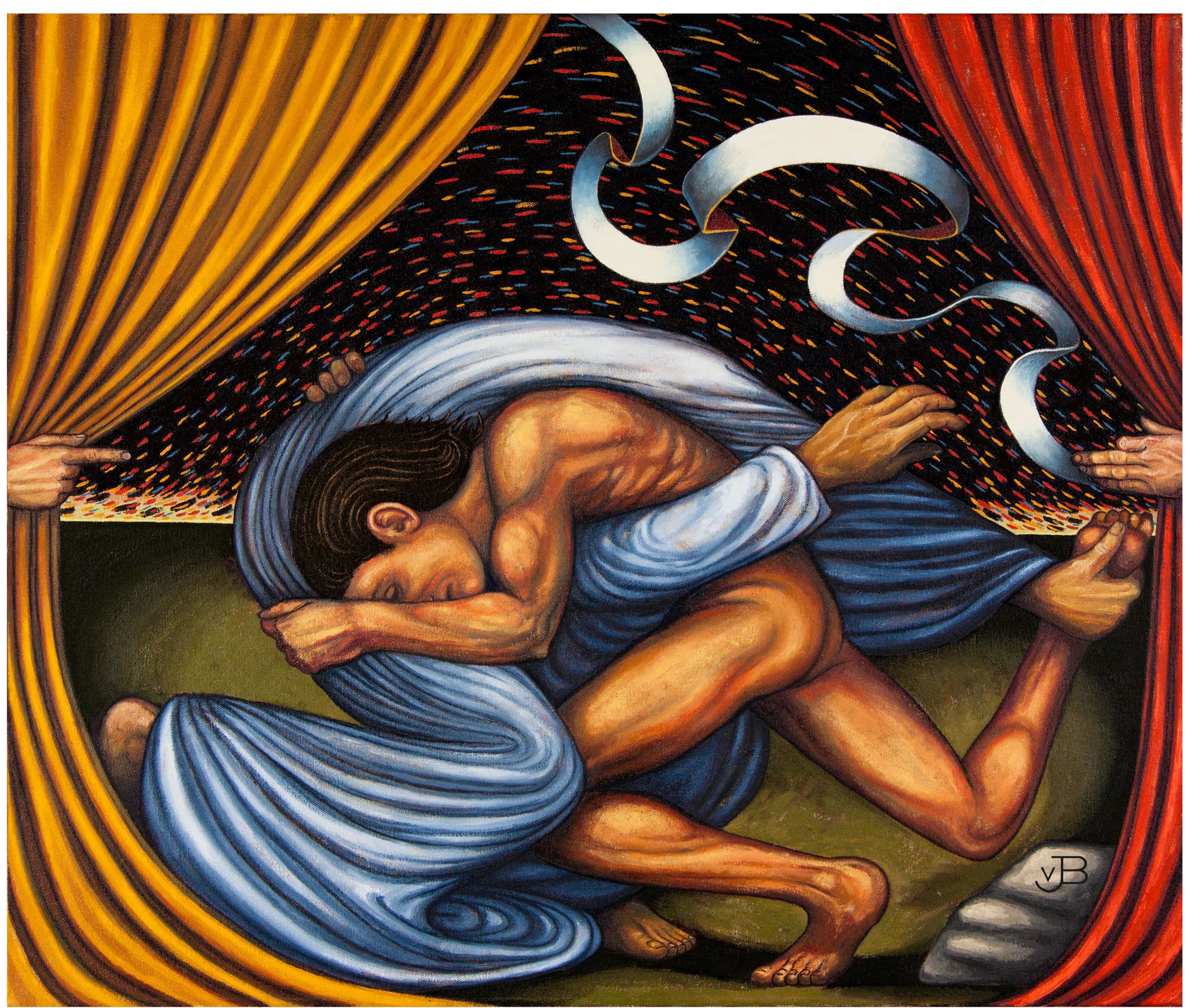

It all starts with this incongruous line: “Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until daybreak.” If we were in grammar school and we turned in a sentence like that, our teacher would send it back to us probably with a big red circled question mark on it. And yet, even though we know that there’s something wrong with the sentence, there is another part of us—a quieter part, a feeling part—that tells us that this apparently bad sentence is really a doorway into a sacred encounter. If you can accept this sentence, you will see something holy. If you can’t accept this sentence, then maybe this passage is closed to you. At least for now. Because, of course, you can’t both be alone and be wrestling with someone all night long. You can’t. You can’t, that is, until it happens to you. And once it happens to you—once you’ve passed through the long, dark night of your soul—you’ll never forget it, and this passage will come alive. But it requires three things. First, and quite easy to come by, it requires turmoil. Second, and more difficult, it requires solitude. And third, and this one is the toughest of all, it requires a willingness to allow the loving Father God we worship and adore to be more than just light and love—to be a God whose blessing can come running out of the dark night and tackle you to the ground. Let’s start with turmoil. Jesus taught us that “the first will be last, and the last will be first.” Jesus asks us to reject the worldly desire to always be the best and have the most. Instead, Jesus asks us to follow the more meaningful way of the Kingdom of Heaven in which values look very different and the order of the world is turned on its head. But Jacob didn’t know Jesus. Jacob lived in a world not so different from the world we live in, where the people on the bottom of the pile had to fight their way to the top by any means necessary. So, as a second son, Jacob had to become a calculating opportunist and a devious liar to steal his older brother Esau’s birthright and to steal his father’s final blessing away from his brother. He believes that he’s willing and able to handle the consequences of his choices. No problem, he says, I’ll just get out of town. So, Jacob runs away from his mess for a long time. Now he’s headed back home with all the riches and the spoils of the driven, self-made, dominating man he’s worked so hard to become—gold, livestock, slaves, wives, concubines, and children. But the only way to get back home is to first pass through Esau’s lands. Now, this isn’t just a geographic issue, it’s a spiritual and psychological one. Once you’ve conquered the world, and you weary of all your exploits, and you want to go home to actually enjoy your life, you’ve got turn around and walk back the path you forged. If it’s a path of peace, you’ll have an easier journey. If it’s a war path you left behind you, you might not be able to overcome your own past. It’s like karma. Whatever you have to face, you have to face it. There’s no other way home. Jacob uses all the tools at his disposal to try to avoid this conflict with Esau—money and charm. He sends all sorts of gifts ahead of him to try to placate his brother. But he feels deep within himself that something is wrong. He fears for his life, he fears for the lives of his family. All these years, to get ahead, he’s relied on deception and distance and hard work. But he’s coming to a reckoning that he can’t smooth talk his way out of, a conflict he can’t sidestep. This moment is going to happen. It was always going to happen. And Jacob begins to realize that it’s not just Esau that he needs to reconcile with—it’s himself. The 12 steps of Alcoholics Anonymous recognize this reality. According to the steps, we must first make a “searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves” (step 4) before we can make amends to the people we have harmed (step 8). Jacob was hoping to skip a step, but he’s realizing that’s impossible. And so Jacob sends everyone on ahead of him, so that he’s alone. There are some people who really don’t like to be alone. Jacob has two wives, two concubines, 11 children, and lots of slaves. Maybe he didn’t like to be alone. Many people who don’t want to be alone are afraid (at least subconsciously) of this very scenario—that once they are alone, they’ll realize that they’re not really alone at all. And the one who confronts them may be angry at having been ignored for so long. A good trickster can deceive the people around him. And while he’s fooling others, he can even outwardly fool himself. But in true solitude, you can’t fool yourself, you can’t deceive yourself. You see yourself as you are, and you have to deal with yourself. This is why solitude can feel so intimidating. It’s also why it should be a regular part of everyone’s spiritual life. Ideally, you spend a little bit of time with yourself every day. Sitting on the train listening to a podcast doesn’t really count. You really nee to be alone and undistracted. Formulaic prayer or silent meditation are a great way to start. Now that we’re alone, the real mystery can begin: “Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him until daybreak.” Who is this man? Jacob asks for his name, but doesn’t get an answer. You’ve already heard in everything that I’ve said so far a very modern, “psychologized” take on this story—Jacob is wrestling with himself. That answers the riddle of how he can be alone and wrestling with someone at the same time. You probably didn’t need me to even spell that out for you. This is just the way we think now as moderns. Now, that’s always been a dimension of the story. But to everyone who came before us, that dimension was best understood by saying that Jacob was wrestling with something GREATER than himself—an angel according to most Jewish interpretation, God according to most Christian interpretation. And this is, in fact, one of the reasons that the story so powerfully captures our modern imaginations—because it confronts us with this lost truth—that when you struggle with yourself, you are actually struggling with God. Or at the very least, who you are becoming in your life is greater than the sum total of who you are now, and can only be accomplished by some form of grace or blessing which is beyond you. You can wrestle with yourself. But in the end, if you prevail, if you are blessed and renamed and transformed into something more, that is not something you won for yourself, that is not something that you did, that is utterly beyond you—that was some greater power than you. That was God. In the end, Jacob's wrestling match illustrates our own struggles to reconcile with ourselves and with God. Though we may try to avoid it, there comes a point in life where we must face the turmoil we have made. In solitude, we’re confronted with the truth of who we are, imperfections and all. And if we persist through that long night, we will find ourselves blessed and transformed by an encounter with the holy which is within us, but which is greater than us. Like Jacob, though we wrestle with ourselves, we do not wrestle alone. The Divine presence that dwells within us and redeems us, is the true source of our struggle and our victory. May we always have the courage to face the truth of our turmoil, to let God tackle us, and to emerge transformed. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed