|

Every year at the church I served in Boston, once a year explicitly, we would send out an invitation to all of the drag queens in the Greater Boston metropolitan area to come to church. Come to church and sing in the choir, come to church and do the special music, do the anthems, do it all. It was a huge fundraising event that we called Drag Gospel Festival. It was a big deal for us. It was like Easter number two. We planned for this thing almost all year long. It was just a sort of a wild ride. And it was a fundraiser for LGBTQ refugees, who in their countries of origin, it was illegal to be gay or transgender. And they had fled to the United States in just the most harrowing stories that you have ever heard in your life. Fleeing imprisonment, torture, death threats, and landing in the United States with nothing, going into immigration detention as refugees. And then this ministry would help to get them out of immigration detention and get them through the refugee process here in the states. It was a wonderful event. My colleague from that church, Rev. Molly Baskette, she has a new book coming out in November, and it is entitled How to Begin When Your World Is Ending: A Spiritual Field Guide to Joy Despite Everything. Some of you are probably familiar with Molly's writings. Here are some excerpts from her book in which she wrote about Drag Gospel Festival in 2015: A few minutes into worship…, I noticed our associate pastor Jeff… sitting uncharacteristically rigid in his chair, staring out, even as bits of feather boas were flying through the air around him. What could possibly be the matter? I leaned over to him. “What’s wrong with you?” I asked. He unobtrusively pointed. “That guy over there,” he answered. “Front pew. Left side. He’s very angry, and agitated.” “I’ll put the deacons on notice,” I said. … As Jeff started reading scripture, I sat next to our twenty-seven-year-old moderator, Ian. I took his hand and asked him to pray with me. “That man—he’s angry. I’m not sure what he’s going to do,” I said. Because the week before: three mass shootings at college campuses. And the previous summer: Dylann Roof killed nine people in their own church, for being Black. And previous to that: that shooting in the Unitarian church, people killed for being liberal Christians. … That was when the man stood up, slowly... He stepped over the front pew into the free space. Turning toward us, he began shouting. And that was the beginning of the five most terrifying minutes and then most terrifying many months of my ministry. The deacons and Molly and I, we managed to diffuse the situation. This man whose name was Drew—believe it or not, he was wearing a name tag—he was not armed. And after screaming at us that drag queens don't belong anywhere in church and Jesus would never put makeup on his face and condemning us, he left. We were rattled, but we weren't defeated. Worship went on and we raised thousands of dollars for LGBTQ refugees. And it was a success. But outside, Drew, who ran in some very, very scary circles. He posted these videos and photos of the event onto his social media. And from there, it got picked up by all kinds of people, all kinds of haters, with YouTube channels and conservative right-wing blogs. And from there, the hate mail and the death threats started rolling in for weeks and for months. They came in over the phones. They came in through the U.S. Mail. They came in over Facebook. They came in by email. People saying things like, “Oh, I guarantee you, somebody's going to burn that church down real soon,” or “I sure hope somebody bombs that church,” or “Somebody better do something about these people.” I was terrified. I was terrified of Drew. I was afraid that he might come back to the church this time armed after getting all this attention online. I was afraid he might show up at my apartment somehow because I was the one he was interacting with most up front, maybe he was thinking of me. I was scared that all the people who are going after us online might figure out who Bonnie was and they might start going after her. We called the police in, but the police weren't able to do a lot in this situation. They said just be vigilant. So I had to be vigilant. I started following Drew on his social media and I put out a Google alert on his name so that I could keep tabs on him. I had to keep tabs on him. Right? I mean, there's no easy way for me to say this. Maybe I'm even trying to avoid saying it up here. But Drew was my enemy. He had made himself my enemy. He did that to me. I didn't do anything to him. And I had every right to be terrified of this man and what he had done to me and to be angry. I was afraid he was going to try to hurt me. I was afraid he was going to try to hurt my family. I was afraid that he was going to try to hurt my church. I assume that you probably haven't experienced anything quite like this, an online vigilante mob coming after you. But I know that you can just imagine how much stress I was under and how mortally afraid I was for weeks and weeks. And so in that discomfort, in that pain, I turned to my Lord and I said, "Jesus, what do I do in this situation?" And what was Jesus' advice to me? You heard it read this morning in our scripture reading. "But I say to you that listen, love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you." Right. So, here I am threatened, afraid, abused. And here comes Jesus, not to make it any easier on me, but to actually make it harder. In the situation I am in, this just makes it harder. What kind of advice is this? I'm the one who's being attacked. How can you seriously ask this of me? Jesus, do you have some sort of secret plan here? I mean, help me out. Is this like reverse psychology or something like, okay, I'm going to make this sacrifice and I'm going to love Drew despite everything that he's doing to me, I'm going to love these people, despite what they're doing to me. And somehow, the power of love is going to get inside of them and infect them and they're going to change. And it's all going to turn out hunky-dory in the end. That's what love does, right, Jesus? That's the real plan, right, Jesus? And what does Jesus say? What does he say in our scripture reading this morning? “Nope. Give without hope of receiving anything back. Love without hope of it being returned. Doing good so that you're going to get some good outcome is not what I am talking about here.” Well, what is that advice supposed to do for me when somebody calls up the church and threatens to hurt me? Well, it all died down after a couple of months, but about two years later, Drew popped up in my Google alerts big time. Because Drew went to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, that now infamous and deadly rally. And he was identified as one of the white men, walking through Charlottesville with a tiki torch at night and chanting "The Jews will not replace us." This was a bit of a change in fortune here. I have to to admit, it kind of felt a little bit good because now that Drew had been doxed, as they called it, now that he had been publicly identified and everybody knew who he was, he wasn't anonymous anymore. And I had the online outrage mob at my back, and it felt so good. Drew wasn't anonymous anymore. Everybody knew who he was. Everybody knew the kind of things that he did to good people like me. He lost his job. He was persona non grata. He was done for. And I felt like after what he had done to me, he got exactly what he deserved. Our reading this morning says, "God is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked." Sure, fine, whatever. How about this for a Bible verse? "Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap." Now you know how it feels Drew. You sow what you reap, couldn't have happened to a nicer guy, as far as I'm concerned. About six months after Charlottesville, Drew was found dead at home. White nationalist and neo-Nazi leaders and influencers online were suggesting that he had taken his own life because he couldn't handle the online bullying from Antifa. Sitting there reading that news, I felt numb. I couldn't help myself. I felt like I had rooted for this outcome a little bit. I felt like I had been a part of that. I didn't want that. I wanted justice. I just wanted justice. I didn't want a tragedy. I really didn't. But maybe when our desire for justice becomes unmoored from the power of love, we might not always be happy at what the justice we get looks like. And in that moment, God sat down next to me and God just said, "Do you see now? It wasn't all about Drew. This was about you. It wasn't about just loving somebody to love them. It was about who you are. This is about not letting hate define your character. It's about allowing me to define your character. Won't you allow me to define your character?" And I said, "Sure, I get it. But I still just think it's terrible advice because I just don't think I'm good enough to love my enemies. I don't think I can do it.” And God laughed at me. I heard God laughing. And God said, "Well, maybe it's not as hard as you think." When my colleague Molly sent me a draft of her book, she reminded me of something I had totally forgotten about on that first day that I met Drew in 2015, this is what Molly wrote: Jeff and Drew continued to talk at a distance, Drew spooling out his speech, Jeff answering him in love but with healthy boundaries. Finally, Jeff said, “You’ve said what you’ve come to say. You’ve been heard. Now it’s time for you to go.” “But one other thing,” Jeff said… “I love you.” Then Drew, turning to face us, said, “I love you too; I love all of you.” … With that, Drew left. [The deacons] accompanied him down the side stairs, where he started sobbing… When he was out of sight, the congregation clapped and cheered, but Jeff stayed the cheering with a raised hand. This was a moment of relief, but not a moment of triumph over another human being. I hadn't remembered that until I read it. I hadn't remembered that I told him, I love you. Now I remember. Now I remember what that moment felt like. It wasn't about being nice to someone who was doing something wrong. And it wasn't about being the perfect man of character. It was about a loving God, so much bigger than either of us stepping in. Do you think you can allow that God to step into your lives?

Well, I'm glad I said it. I'm glad God stepped in. And in fact, I'll let God step in again: Drew, I love you. You didn't make it easy, but I love you. And I'm sorry that I forgot. Let us pray. God, thank you for being kind to the ungrateful and the wicked, even when I just can't stand it. Thank you for being kind to me when I'm ungrateful and wicked. Thank you for the love that is so much bigger than any of us. Amen.

0 Comments

As Christians observing Black History Month, I think it’s important for us to celebrate the contributions of Black people not just to our secular society, but also to our faith. And to put the contributions of Black Christians and the Black Church in proper perspective, we’ve got to acknowledge that there have been broadly two versions of Christianity in American life. the first is slaveholder religion—a white supremacist religion that preached that God made White people to rule and Black people to be held in bondage to White people. It taught that slavery is not only a natural condition, but a God-ordained one (for Black people only, of course). And it claimed that Black people were not created in God’s image and that Black people are less than human. After slavery ended, slaveholder religion adapted itself to the changing times. Now, it blessed segregation, sanctified Jim Crow, and presided at lynchings and cross burnings across the country.

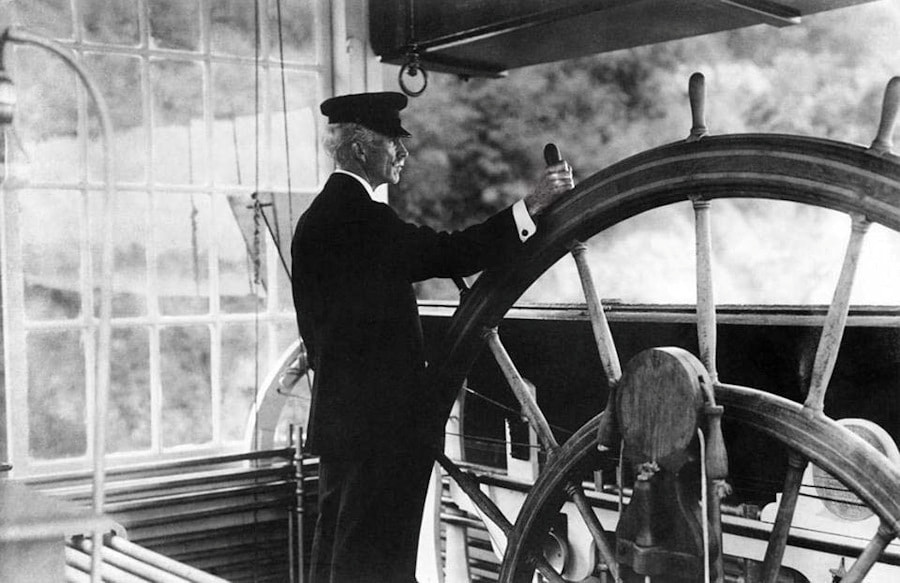

The Christian ancestors I admire come from the other broad category of Christianity in American life: the Christianity of those few White people who refused to accommodate or compromise with slaveholder religion or racism, and, more importantly, the Christianity of Black people in America who believed that our God is a God who chooses the slaves of the world over and against the pharaohs and the slavedrivers of the world. It was in the underground churches of the persecuted and oppressed that the light of Christ’s gospel held back the darkness that had overcome so much of the rest of the Church. One of the tenders of that light was Sojourner Truth. She was born into slavery as Isabella Baumfree in 1797 just a few miles up the Hudson in Rifton, NY. She was sold multiple times before she was 13 and suffered a great deal of abuse, separated from her parents, watching her own children sold in slavery. At 30 she escaped and, following a vision from God, she made her way to the house of a Quaker family who bought her from her master and freed her. Eventually she renamed herself Sojourner Truth and she became an itinerant Christian preacher, abolitionist, and suffragist. She once told a gathering of abolitionists and clergymen at Harriet Beecher Stowe’s house, “The Lord has made me a sign unto this nation, an' I go round a'testifyin' an' showin' on 'em their sins agin my people.” Truth couldn’t read so she didn’t write down her speeches and sermons, but some were written down by others who heard them. The most famous of them was given at a Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. Truth said: "That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages and lifted over ditches and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody helps me any best place. And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm. I have plowed, I have planted, and I have gathered into barns. And no man could head me. And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne children and seen most of them sold into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me. And ain't I a woman?" Appearances, Truth is telling us, can be deceiving. If you believe women are weak because of their social position, then you do not understand strength the way God sees strength; you do not understand power the way Jesus preaches power. A few years back there was a Frida Kahlo exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum called “Appearances Can Be Deceiving.” When you walked into the exhibit you were overwhelmed with color and strength. The opening rooms of the exhibit were filled with the paintings and photographs of Frida Kahlo the cultural icon—the impassive, beautiful face; the gorgeous, brightly colored dresses; the striking eyebrow, the passionate marriage to Diego Rivera. One of the first items on display was a photo of Kahlo at 19. She’s staring right into the camera with such cool, poised confidence you would never know that just a few months before she had been in a horrible trolley accident that had almost killed her and left her with injuries and pain and complications that would plague her for the rest of her relatively short life. She’s carefully posed in the portrait, sitting on a chair in a way that hides her injuries—both from the accident and from a bout with childhood polio. Looking at the photograph, without knowing the context, you would never guess that pain that was being masked by it. But then in the final room of the exhibit, you finally got to see all the context. Here were Kahlo’s disability and suffering—her prosthetic leg is on display, the broken columns she frequently painted as a depiction of her spine were here, there were drawings of her lost fetus, and, standing all in a row, the medical plaster corsets that she suffered inside of for months at a time. Halfway through this final room, you came to a drawing of Kahlo’s that is like a self-portrait x-ray. In it you see right through her beautiful indigenous dress to her naked, broken body beneath it—her injured leg, her tortured back, her empty womb. Written beneath the drawing are the words, “Appearances Can Be Deceiving.” The illusion is peeled back, and we’re confronted with the truth that Kahlo’s greatest art slams head on into the greatest sufferings of her life—her injuries, her miscarriage, and her difficult relationship with her husband. In fact, I think that all of Kahlo’s art and all of her presentation of herself can be traced back ultimately to her struggles. So, just like with Sojourner Truth, it’s not just Kahlo’s physical appearance that could be—at times—deceiving. We see in this final room that we have also been deceived about the source of her power. Was Frida’s Kahlo’s art inspired by privilege and good fortune? Was Sojourner Truth’s source of power a God who blesses the best of us with privilege and comfort? Where us the blessing and where is the woe in these women’s lives? Where does their power and where does our power come from? In Advent, two months back, Luke told us that after Mary conceived Jesus, she went to visit her cousin Elizabeth and she sings. She sings that God throws down the powerful from their thrones, lifts up the lowly, feeds the hungry, and sends the rich away empty. She does not sing that God will do this, but that God has done this. Don’t be deceived! Mary releases a great energy into Luke’s gospel, right at the beginning, like tipping a big stone over the edge of a hill. That stone rolls right into Epiphany when, three weeks ago, in Jesus’ very first act of public ministry, before he does anything else, he goes to Nazareth and reads from the Isaiah scroll: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because God has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. God has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord's favor.” And then Jesus tells the gathered crowd, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled!” Do not be deceived! Today! Not tomorrow. Right now. And it feels like that big stone Mary pushed is now bouncing and leaping and cracking down the mountain. And today, immediately after choosing the twelve disciples, Jesus also comes down a mountainside to a level place and gives them all—disciples and people—their first lesson. It is simple, concise, clear, and concrete: You who are now poor, hungry, weeping, and despised are blessed because the Kingdom of God is yours. And you who are rich, filled, laughing, and respected are now so full that you are likely to remain empty. We hear from Mary that God is doing great things for the poor and casting down the powerful. We hear from Jesus that God has sent him to bring good news of liberation to the poor and imprisoned. And now we hear from Jesus that our whole assumption, the perspective of seeing the poor as low and the rich as great, is the great deception. We’ve gone past the tipping point and suddenly that stone bounding down the mountain is bounding back up the mountain again! and the world we know is upside down. And those of us who have been praying for God’s blessing begin to wonder if God’s idea of a blessing and our idea of a blessing are at all compatible. And those of us who desire to be powerful and effective and good in the world are forced to ask ourselves what God’s power, and justice, and goodness manifest in the world will really look like. Will it be a vision that well-off, well-fed, happy, and respectable folks—innocents who know nothing of the world’s true suffering—can pull off? Where does our power come from? Sojourner Truth, a black woman born into slavery believed that her power came from the power of Jesus in everything—even within her, giving her the perspective to illustrate with her life that what the world calls weakness, God calls strength; what the world calls inferior, what the world enslaves, what the world puts chains on, that is the social position from which God sees the world, from which God moves and acts and judges. Frida Kahlo’s power came from artistic expression that defied but never denied her suffering. She also never deified her suffering. She didn’t pursue it or celebrate it, she confronted it, she harnessed it, she transformed the lead into gold. Jesus says it so matter-of-factly that it’s dumbfounding. You can only be a disciple of my Way if you recognize that in a world of haves and have-nots, God is not located in privilege or good fortune, but in the lives of those who hunger. Beloved, do not be deceived. If you want to respond to a suffering world, you cannot do it, ultimately, from the places that are well-off, well-fed, happy, and respected. You need to find the place within you that is suffering, has suffered. Find your hunger, find your disgrace, find your failure, and there you will find God waiting to respond not just to you, but to a whole world in desperate need of grace. Don’t listen to the satisfied ones who say that suffering is a curse from God. Listen instead to God, who promises: We will not be defeated by this, together we will turn it upside down until it is a blessing. There are two ways (so I’m told) to pilot a boat down the Mississippi River. The first is to know the location of every hazard that could sink a boat for thousands of miles up and down that river. We admire this approach–it’s data driven, which we like. We’ve come to believe that information can save us, so the more the better. Bring it on!

But there’s another way to approach the river. An old story tells it like this: Once a little boy asked a captain how long he’d been piloting his boat up and down the Mississippi. “Forty-four years.” “Oh,” said the boy, “then you must know where all the rocks are, all the shoals and sandbars.” “No,” said the pilot, “But I know where the deep waters are.” Where are the deep waters? How do we find them? How do we trust them? Knowing the rocks and navigating the deep waters are not the same thing. How many of us have read a self-help book, or a book about spirituality, or parenting, or leadership, or anything, and come away with a lot more info, but still feeling disconnected to it somehow? How many of us have ever fished all night long, but still caught nothing? Well, to begin with, our reading this morning reminds us that, just like that old Mississippi River boat pilot, Jesus knows where the deep waters lie and he’s ready to lead us to them. The question is: Am I willing ready to follow? The disciples said yes, and I’d like to know why because there were plenty of good reasons to say no. For example, in 1986 a couple of scientists interested in fisheries management in Israel got together to measure the biomass in Lake Kinneret (which is the modern name for the body of water called the Sea of Galilee or the lake of Gennesaret in our Bibles). They used echolocation to map out where all the fish lived in the lake. And they found that 80% of all the fish—of all sizes and all species—lived in the in-shore region of the lake at a depth of less than 10 meters. Go out more than a few hundred meters from the shore, where the lake gets a little deeper, and the population of fish drops dramatically. Go miles out, to the deepest waters, and there’s almost no fish at all. That’s an important data point for fishermen, wouldn’t you say? Now, they certainly didn’t have sonar, but Peter and James and John and all the fishers down at the lake, from generations of experience, must have known where to fish—close to shore, where it’s safe, and where all the fish live. And here comes Jesus—a carpenter’s son with no connection to fishing—telling them to drop their nets in the deep water. Well, they would have known that the deep water was the last place you could hope to catch anything. Jesus was asking them to go fishing in the wrong spot! Now, really, why would they do that? Would you be willing to do that? We’ve come to believe that failure is caused by one of three things: using the wrong technique, not trying hard enough, or not having sufficient data. But the disciples were using the right nets and the proper boats, they’d worked all night long (they weren’t being lazy!), and they were in the right spot, right where all the fish lived, and they still failed. Imagine with me what Simon Peter may have been going through that night. Maybe Simon Peter is just right on the cusp of realizing that his failure to catch fish has nothing to do with his technique, his equipment, his effort, his data. And Jesus comes along to nudge Peter’s spiritual intuition that breaking through gridlock requires an imaginative risk. Maybe Simon Peter going out there to the deep waters wasn’t just some act of pious obedience to the Son of God. Maybe he was beginning to see that it’d be foolish to stay stuck with the failures of the right spots. So, he risks the disruption of succeeding in the “wrong spots.” Rabbi Edwin Friedman once wrote, “Any renaissance, anywhere, whether in a marriage or a business [or, I would add, a church], depends primarily not only on new data and techniques, but on the capacity of leaders [all of us!] to separate [our]selves from the surrounding emotional climate so that [we] can break through the barriers that are keeping everyone from ‘going the other way.'” In other words, Beloved, church, what we’re doing here together—recovering from COVID, learning how to be back with one another in person again, learning how to grow and change and succeed in new ways, and reversing some of the downward trends that we’ve been stuck in—will not be motivated by having a “business plan.” It has almost nothing to do with gimmicks, almost nothing to do with whatever the latest church-guru has cooked up for publication, and almost nothing to do with hard work. The motivation for progress has everything to do with our emotional availability. Are we willing to leave behind the gridlock of where we are “supposed” to be for the risk of answering God’s calling out in those deep waters? Jesus seems to be saying to us, “This is the prerequisite to discipleship—a willingness to defy your own conventions and to risk success in the places that you previously never thought go.” So, Jesus calls them out to the wrong spot, to the deep waters that they don’t know, and those fishermen catch such a haul that it almost sinks their two boats. Don’t let anyone ever tell you that failure is riskier than success. Sometimes success can capsize the comfort of our failures. Just look at what success does to Simon Peter: He falls to his knees in the boat in front of Jesus in the full realization of just how stuck he had been. And all the ugly emotions begin to pour out—shame and fear. “Go away from me.” But Jesus says, “Don’t worry, from now on you’ll be catching people.” Rev. Debbie Blue once referred to this as a “potentially gruesome metaphor:” All those fish trapped, flopping, squirming, their little eyes bulging, their little mouths opening and closing, gills flapping, their little brains trying to comprehend what’s happened. But it really doesn’t have anything to do with the fish. That was part of Simon Peter’s realization—It’s got nothing to do with the fish; this is about me! Jesus takes these fishermen as far away from the crowds on the shore as possible—to the center the lake. They withdraw there to the deep waters and let down their nets. And God shows up in abundance. God shows up so much that it almost sinks the boat. And now, after encountering God, Jesus tells them what ministry is really all about—not fish, but people. This is like the in-and-out deep breathing of Jesus’ Gospels: God and neighbor, God and neighbor, God and neighbor. To get unstuck—to break the imaginative gridlock of times like these—requires us to turn away from safety into risk, to turn away from hard work and into God’s work, to turn away from my ego’s preferences and toward “the wrong spots,” to turn away from myself and to turn toward my neighbors. And, Beloved, once we break away from the gridlock, once we get curious and adventurous, and begin to explore the deep waters, it will transform the way we pilot the boat of our lives: less anxiety, less paralysis, less despair. We’ll leave all the rocks behind, and let the deep waters carry us down the river. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed