|

Preaching on: Philippians 2:5–11 Mark 11:1–11 In the Gospel according to John, Jesus’ first miracle was to turn water into wine at a wedding. Not a glass of water into a glass of wine, mind you. Jesus transformed six stone jars each holding 20 or 30 gallons of water into fine wine. That’s somewhere in the range of 600 to 900 bottles of wine. Because before Jesus ever preached a word of the Kingdom of God, before he ever came face to face with a world of sickness and poverty and sorrow, Jesus attended and served our joy. And this isn’t some heavenly “joy” so stripped to the bone that no one would ever want it. This is a party! This is carousing! This is 180 gallons worth of laughter, dancing, and celebration! Real, human, incarnated, communal joy.

And it wasn’t a one off either. Jesus described himself as the Son of Humanity who has come eating and drinking. And his critics would complain about him, “Behold, a glutton and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners.” Jesus was no John the Baptist eating locusts out in the dessert. No one would ever have accused John the Baptist of having too much fun. But Jesus’ ministry often happened at tables with food and wine and undesirables. For Jesus, repentance and joy were not incompatible. Repentance was a return to God, and a return to God is joy. And so from the beginning of Jesus’ ministry we now arrive at the beginning of the end. Jesus is days away from being betrayed, being arrested, being crucified. He’s days away from his own death. But his joy hasn’t left him. Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem has come to be known as the Triumphal Entry, but we could just as easily call it the Joyful Entry. It’s a parade. It’s street theater. It’s a demonstration. It’s fun! Joy radiates out of the parade’s center—radiates out of Jesus. It infects the whole crowd. And precisely because it’s fun and precisely because it’s full of joy, it’s the ideal event to draw people in, to make them want to participate, and to help them understand that Jesus’ values are their values. This is a sermon about joy, but here we have a question we need to take seriously as Christians and as the Church: Where is our joy? How often does our worship of God spill out into the streets? How often do we make ourselves a public spectacle? How often do we risk looking foolish (the way that Jesus almost certainly looked foolish riding on the colt of a donkey)? How often do passersby take a look at what we’re up to and say, “Hey, I don’t wanna miss this!” All this Lent one of our themes has been Lent of Liberation. We’re reading a Lenten devotional by that name that hopes to empower us or challenge us to confront and reverse the detrimental legacy of slavery for Black people in America. In order for us to have this conversation (or any conversation we might have about race, racism, and privilege) requires us to cultivate certain values or virtues—virtues that makes us good communicators both in speaking our truth and in hearing the truths of others. So, this Lent I’ve been preaching about virtues. I started with humility, courage, and compassion. But I worried a little bit about recommending virtues that are really so well inside our comfort zones. Because I think so often we Christians think of ourselves as the stable, respectable, virtuous types. And we can get stuck there. And we can take ourselves a little too seriously and we can be a little dour. The “frozen chosen” as we’re sometimes called. And we impose this stereotype back on our whole tradition, back on Jesus, and back on God. When we do that, I think we really idolize our own respectability rather than allowing God’s loving, and Jesus’ outrage, and the Holy Spirit’s ecstasy to transform us into the people God desires us to be. We have to remember that Jesus was not respectable. He was an outsider, a rabble rouser, a baby donkey rider, and this morning he is days away from being just another executed criminal, just another Jewish dissident dead on a Roman cross. Which is why for these last three weeks of Lent I’ve tried to round out our respectable virtues with some virtues that are much more suspect—anger, longing, and today, most important of all, joy. Joy gets a lot of lip service in the Church, certainly, but real joy, true joy—180 gallons worth of the finest, street-parading, crowd-rousing, slain-in-the-Spirit joy, does not often come out of the closet in most of our churches. We keep real joy in the closet because we’re respectable people with reputations to think about. And if joy comes out of the closet, we’re afraid of what might come along with it. Because once joy is really and truly out the closet, soon the joy of children comes of the closet as well. And the children are dancing and singing in the aisles during the hymns instead of being hushed and sent off. And then the joy of sex slips out of the closet. And people refuse to be ashamed anymore of who God made them to be or who God calls them to love. And the LGBTQ community, who have refused to die in the closet unacknowledged and unfulfilled, might begin to show up in numbers, in marriages, in families loud and proud and fabulous. And then there will truly be nothing left of our dignity to prevent us all (to borrow a phrase from Dan Savage) from skipping off to Gomorrah. We are commanded to love God with all our heart, soul, and mind, not to love respectability. And in the in the commandment that follows it and is like it, “love your neighbor as you love yourself,” the operative word is “love.” It cannot be reformulated, “repress your neighbor as you repress yourself.” Joy is at the very heart of the expression of love. If we don’t get joy right, we can’t get love right. In fact, I’ll go even further than that. What use is any virtue if it makes you miserable? Remember what Jesus tells us every Ash Wednesday: If you’re going to fast this Lent, don’t be miserable about it. Don’t go around crying about it. Wash your face! Anoint yourself with oil! If you’re miserable about it, you’re just wasting your time. Now, I’m not saying abandon all virtues or activities that are hard or challenging or uncomfortable to you and pursue the vices instead for cheap thrills. I’m saying that God is at the heart of all virtues. Therefore, joy is at the heart of all virtues. And if we practice a humility or a courage or an anger or a longing that isn’t joyful—deeply, soulfully joyful— we’ve missed the mark somehow. Virtues without joy are dead. Jesus on Palm Sunday is the embodiment of joy in virtue. He is going to the cross to die. He’s riding on a baby donkey like a clown. But Jesus is answering his calling with a joy that we still feel today. We still wave our palms; we still shout Hosanna. Why? What is it that moves us about this story? We see Jesus fulfilling his highest calling. We see him putting together a bit of a show for us. We see the twinkle in his eye. The mischievous little twist of a smile on his face. We feel what I think the crowd must have felt when they saw him, “Well, I’ll be gosh darned! He’s doing what? Crazy son of a gun! Look at him go! I don’t want to miss this!” And finally here is my best answer to how can we hope to have productive and empowering conversations with people who have truths to speak that are different than our truths, challenging of our privilege, and uncomfortable to our consciences. The answer is we must make a joyful entry enter into the conversation and into the relationship. It won’t always be easy to discuss what is dividing us and what is killing some of us or what the remedies are. I’ve found myself a little depressed and sometimes in tears and sometimes feeling a whole range of difficult and unpleasant emotions as I work through the daily devotionals of Lent of Liberation. But I return to my reading each day with joy because I know that the truth contained in these pages is a truth that brings me closer to my neighbors and closer to God. And a return to God is always a joy. Beloved, Paul tells the Corinthians in our reading this morning that they should let the same mind that was in Christ Jesus be within them. Now the word translated “be of the same mind” here in the Greek wasn’t just a word about thinking, it was also a word about feeling. You could also translate it, “be of the same heart as Jesus.” Jesus, who gave himself to his calling and to the cultivation of his best spiritual gifts and who through humility, and emptying and longing, and courage, compassion, righteous anger, a bit of foolishness and theater, and a whole lotta wine achieved a joy that could not be contained, that spilled out of him. “If the people were silent, the stones would shout!” he says in Luke’s gospel. If the stones can shout, then there’s hope for me, Beloved. There’s hope for all of us that we too can enter into God’s joy.

0 Comments

Preaching on: John 3:14–21 Let me begin this morning by reading you a rather steamy little love poem… Take a deep breath because this is more of a 10 o’clock at night poem than a ten in the morning poem, if you know what I mean:

How beautiful you are, my love, how very beautiful! Your eyes are doves behind your veil. Your hair is like a flock of goats, moving down the slopes of Gilead. Your teeth are like a flock of shorn ewes that have come up from the washing, all of which bear twins, and not one among them is bereaved. Your lips are like a crimson thread, and your mouth is lovely. Your cheeks are like halves of a pomegranate behind your veil. Your neck is like the tower of David, built in courses; on it hang a thousand bucklers, all of them shields of warriors. Your two breasts are like two fawns, twins of a gazelle, that feed among the lilies. Until the day breathes and the shadows flee, I will hasten to the mountain of myrrh and the hill of frankincense. You are altogether beautiful, my love; there is no flaw in you. Come with me from Lebanon, my bride; come with me from Lebanon... You have ravished my heart, my sister, my bride, you have ravished my heart with a glance of your eyes, with one jewel of your necklace. How sweet is your love, my sister, my bride! how much better is your love than wine, and the fragrance of your oils than any spice! Your lips distill nectar, my bride; honey and milk are under your tongue; the scent of your garments is like the scent of Lebanon. A garden locked is my sister, my bride, a garden locked, a fountain sealed. Your channel is an orchard of pomegranates with all choicest fruits, henna with nard, nard and saffron, calamus and cinnamon, with all trees of frankincense, myrrh and aloes, with all chief spices-- a garden fountain, a well of living water, and flowing streams from Lebanon. Phew! My Goodness! What a love poem! What eroticism! That deep desire and longing. My, my, my. If you’d like to find a copy of this poem for yourself, all you need to do is open your Bibles. I was reading you the fourth chapter of the Song of Songs. How’d something like that make is past the decency police? My goodness! Well, it’s all about interpretation. Traditionally, the Song is spiritualized—whatever its origins, we read the Song as being about God’s relationship with Israel, or Jesus’ relationship to the Church, or God’s relationship to the individual soul. It’s not about two lovers, it’s about God and us. It’s about God and you. And I want you to hear that desire this morning—God’s desire for this world and for all of us. I want you to hear that longing this morning. It is not a minor longing. Is it? It is not a sterile longing. Is it? It’s not merely an intellectual or even a spiritual longing. Is it? It’s better to compare God’s longing for us to the most sacred longings of our bodies and souls—falling in love, the quickening of your pulse and your breath when you see your lover, being ravished by a look, by a brush of the hand. This is something like how God feels about us. Keep that kind of longing—that depth of longing—in mind as we come to Jesus’ words this morning: “For God so loved the world that God gave God’s only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.” God longs for us so much that God became one of us. God poured herself out for us. I’m not talking about crucifixion, I’m just talking about incarnation. God incarnated herself, enfleshed herself to become a creature like us: a creature with a body, with desire, with longing, with hands for touching and healing, a mouth for speaking to us and eating with us, eyes to look at us with, a heart that would beat faster at the sight of us. A creature with limitations and all the risks of pain, and vulnerability, and discomfort, and hurt that come with life. God risked it all, even death. God poured herself out into Jesus not just because God loved the world, but because God so loved the world. Because God longs for us, God isn’t satisfied with just loving us at a distance. God longs to be with us, to be near us, to touch us, to be as close to each of us and to all of us as it is possible to be. But God isn’t a bully. Or an abuser. Or a tyrant of souls. Our God is not like Zeus coming down like a bull to carry us off willing or not. In order to be united with God we have to return that longing. It has to be mutual. As the great preacher and mystic Howard Thurman would say, we must turn over the nerve center of our consent to God. We, as Christians, come to God through Jesus, just as God comes to us through Jesus. Jesus is the body where divine longing for the human and human longing for the divine meet. Beloved, what do you long for? What do you desire most? Our relationship to our longings and desires is complicated. Do you know five of the seven deadly sins are about longings? Envy, greed, gluttony, lust, and sloth. That’s a lot of pressure on our desire—a lot of negative attention. We’ve been taught that too much desire is dangerous and that not enough desire is unhealthy. And threading the eye of that needle never seems graceful, it always feels like we’re missing the mark. Desire is supposed to be joyful. But how often do our longings bring us closer to true joy? We live in this materialistic, capitalistic, consumer society that depends on our longings (and even sometimes our addictions) to keep the economy going. We all need to do our part! Marketers and advertisers manipulate us and highjack our desires. Not happy with yourself? Frustrated with the state of the world? Modern life totally unmanageable and dissatisfying? Buy this! Binge that! Ask your doctor if new Meanaride is right for you! We’re all born with longing. Longing is there to keep us alive, to direct us to the best things in life (like love, beauty, joy), and ultimately our longing is what connects us to one another—lovers, parents and children, friends, family, community. God made longing for us, God gave desire to us. But we’ve grown suspicious of desire, we’ve made it illicit, we’ve filled it with alcohol and sugar and plastic. We’ve disconnected and disrupted our lifeline to God and to one another. God is singing to us, like a lover calling the beloved to the window just to catch a glimpse of us. But where have we placed our desire? What do we long for? We can’t ignore that once again this Lent we’re being faced with questions about salvation. Two weeks ago, we spoke about Jesus’ bottom line in Matthew’s gospel. There Jesus says if you care for the needs of the least of these, you care for me. If you ignore their needs, you reject me. Those who feed the hungry, clothe the naked, heal the sick, and visit the prisoners will inherit eternal life. Those who do not will be sent into eternal punishment. Clearly, salvation has something to do with judgement and with eternal life. Matthew’s Jesus says the bottom line is how we treat the most vulnerable and marginalized people. Jesus tells us that our connection to God is inseparable from our connection to other people. The greatest commandment is love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind. And a second is like it: Love your neighbor as you love yourself. But in our reading this morning, John’s Jesus seems to say the bottom line all comes down to how you believe in him. And it’s from here that we’re taught that we need to believe in Jesus who came into the world not just to be with us but to die for our sins, and when we believe in Jesus we accept that sacrifice so that we can go to heaven. But thinking about this longing, is forgiveness and a trip to heaven all God desires for us? This God who desires us so completely. This God who came to us on earth to show us how to live with one another and how to treat one another in life. It seems to me that God wants to get inside the innermost longings of human existence. God wants her longing and our longing to become one mutual longing. God doesn’t just want to forgive us and then snatch us off to heaven after we die. God wants her love to transform us in this life. She longs to become the nerve center of our consent. She longs to be in relationship with us, with all of us, not just as individual saved souls, but as a whole loving, caring, mutual, transformed world—for God so loved the world. Beloved, the beginning of faith, the beginning of meaning, the beginning of any kind of relationship is longing. It began with God’s longing for us. God created us out of a longing to be with us. God entered the world through Jesus because God longed to be closer to us. But we must respond to God’s longing for us with our own longing for God and for one another. I believe that we’re born with this longing. It’s a longing for what is most true, most important, most beautiful, most good. It’s a longing for love, and touch, and food, and water, and sunlight, and joy, purpose, fulfillment, relationships, community. If we follow this longing, and if we don’t let anyone squash it or let anyone make us feel guilty for feeling such passion for life and love, if we let it guide us and grow us, our longing leads us to good things, it leads us to God who is at the heart of our deepest longings—God who is the missing answer to the questions we can hardly put into words. But there are so many things competing with our attention, competing with our desire for the things that are good for us. Things that do not have our best interests in mind. And, so, we must long for the light. We must long to be seen so that we can see others. We must long to be known as we truly are, and long to know others as they truly are. Fear will never bring us out of the dark. Fear will never open us up to God or to one another. Fear and sealed off opportunities and unfulfilled needs will never open up the doors of heaven. It is only love that can do that—longing. How can we believe in Jesus if we don’t long for him? How can we care for the least of these if we don’t long to be with them? Beloved, belief is not merely an intellectual assent. It’s a longing that draws us ever closer to God. A longing that empties us and fulfills us. Care is not flinging a coin to a beggar. It’s a longing that draws us ever closer to our neighbors. A longing that empties us and transforms us. What do you long for? What do you desire most? Preaching on: John 2:13–22 In 2006, while I was at Union Theological Seminary, I began a ministry to New York City’s restaurant workers. Being the largely self-proclaimed Chaplain to the New York City Restaurant Industry was a ministry, but it wasn’t exactly a job. And so to pay the rent I was also working in the industry myself as a busboy at a fine-dining restaurant on the Upper West Side. I met a lot of great people, including one of my fellow bussers, Alberto.

It took a while to get to know him because he was kind of a shy guy—which is actually perfect for us busboys. We hover at the edges of the dining room watching our tables sharply and silently. Ideally, we shouldn’t ever be noticed. Just before a water glass is emptied we swoop in, fill it, and slip away. When a dirty napkin is dropped on a chair because of a trip to the restroom, we glide to it, fold it, and lay it back on the seat with quiet deference. When a course is completed, we make eye contact with one another, nod in coordination, and come to the table from multiple angles, clearing every dish and piece of silver no longer needed in the blink of an eye. With our arms loaded up and our heads down, we rush out through the kitchen doors. If a busboy does get noticed, it’s almost universally a bad sign—a shattered glass, a splattered sauce, and the dreaded, “I’m not done with that yet!” I once tried to clear a diner’s amuse bouche, and she threatened to stab me with her oyster fork. I slid back into the corner with a smile neither amused nor offended, like an aproned automaton. It does no good to get angry when you’re a busboy. It’s better not to be noticed. And Alberto was good at not being noticed, which made him a good busser. He was introverted. He never raised his voice. He never laughed or fooled around. He never seemed to get bored or tired. He never bickered with the servers or the managers. After a while, working together night after night for months, when the restaurant was slow, Alberto began to whisper with me in the dark corners of the service area while we watched our tables. He was naturally quiet—even the other Spanish-speakers thought so—but he was also embarrassed by his English. He had a lot of trouble with the pronunciation and enunciation of English words, so we would practice together. He would say an English word he had learned, I’d repeat it back, he’d try to parrot me, I’d repeat it again, slowly articulating each sound. He’d imitate me again and again, trying to contort his lips and tongue into unnatural poses. It was the first time I saw flashes of emotion in the man—anger. Alberto was frustrated with the way he sounded. He kept practicing, but mostly he just kept his head down, stayed quiet, and bussed his tables. Based on our Gospel reading this morning, Jesus doesn’t seem like he’d make it as a busboy. Flipping tables over, yelling, whipping the customers, arguing with the managers, threatening to burn the place down—none of these things for a good busboy makes. It’s easy to assume that Jesus must have just been made this way—born to be the new sheriff in town!—and that this is just the kind of behavior we should expect from the Son of God—outspoken moral indignation from a Messiah who’s fearless or reckless (or both). But Jesus’ behavior in the Temple, here in the second chapter of John’s gospel, is very different than what we’d expect from this Jesus based upon what comes before it. In the beginning of John’s gospel, John the Baptist shouts out in the wilderness just like we expect. But when Jesus shows up there’s no baptism scene. Jesus doesn’t say or do anything. He just shows up. John sees a dove descend on Jesus and John starts calling Jesus the Lamb of God in front of everyone. Jesus doesn’t even seem to notice. The next day Jesus walks away (so far Jesus has shown up and left—that’s it), and two of John’s disciples decide to follow Jesus—not because Jesus calls them to follow, but because of what John is saying about Jesus. That evening, one of these new disciples takes it upon himself to recruit a third person. Jesus doesn’t even go with him. Two days later Jesus and his friends go to a local wedding in Cana. Jesus’ mother famously complains to him about the party running out of wine, and he says to her, “What does that have to do with you and me? My hour has not yet come.” But she manipulates the situation as only a mother knows how, and Jesus turns some water into wine. But it’s not like he makes it a big production, waving his hands around and saying “abracadabra.” He doesn’t even get out of his seat. He just says, “Fill those jugs up with water and then drink out of them.” He’s like a busboy slipping in to magically refill a wineglass without the guests even noticing—inconspicuous. When people start freaking out about how good the wine is, Jesus lets the groom take all the credit. Then Jesus leaves for Passover in Jerusalem, he takes one look at the marketplace that had always been in the Temple, and the next thing you know he’s whirling a whip over his head and inciting a riot. How does something like that happen? How do you go from being quiet and unassuming to a full-blown rabble-rouser with the turn of a page? I think maybe Jesus got angry! Did you notice that too? So far this Lent we’ve talked about humility and courage, and last week when we talked about the Amistad we started to talk about compassion and justice, but anger? Could anger be virtuous? But Jesus is doing more than just feeling anger and then calmly responding like you would think some sort of holy person would. He seems to be acting out of anger. Can anger be righteous? Productive? Holy? The other three gospels in the Bible—Mark, Matthew, and Luke—they place this story about Jesus attacking the Temple marketplace near the end of their gospels—right before the crucifixion. In fact, Mark makes it clear how dangerous this action was—Mark implies it’s the inciting incident of the crucifixion: After witnessing this action the Temple authorities decide they have to destroy Jesus, in Mark’s Gospel. But John makes this public protest the inciting incident not of the crucifixion, but of Jesus’ whole ministry. In John’s gospel Jesus’ first public action is an action of anger. Well, what was Jesus so angry about? There were all kinds of currencies available in Jerusalem, especially since Rome had come, but only Shekels of Tyre could be used to pay the Temple tax or to do business within the Temple. That meant that if you were a peasant who came into Jerusalem to fulfill your religious obligations during, for instance, Passover, you were at the mercy of exorbitant exchange rates at the moneychangers’ tables. If the festival you were in town for required an animal sacrifice or if you needed to sacrifice an animal for purification, you couldn’t bring your own homegrown animal to Jerusalem on a leash the cheap way. You had to buy a “pure” animal from the sellers in the Temple. “Pure” animals cost much more than the same animal being sold just outside the Temple walls. If Jesus is angry, his anger is righteous anger. It’s not that money or animals are offensive to God, it’s that corruption and preying on the poor are offensive to God. Cows in the Temple are not profane. Injustice in the Temple is the profanity. A system that exploits the poor is immoral, and Jesus’ demonstrates to us that the suffering the poor endure because of such a system is one of God’s ultimate concerns. Jesus’ righteous anger is not a self-righteous anger that obsesses over the transgressions of the sinners. It’s a compassionate anger that is deeply concerned with the suffering of the least of these. Now, I worry about anger. I worry about it because I know from experience just how destructive anger can be. We’ve all seen it happen. We’ve seen anger eat away at someone from the inside. We’ve seen anger burst forth out of someone with violence and hatred. Anger is a powerful emotion. And if it’s not handled properly, it can destroy good things and do terrible things. But there are also times when a lack of anger is the true problem. Apathy in the face of injustice, not bothering to have a reaction to the suffering of others, not caring about systems of abuse and exploitation, not believing that you or that others deserve better can be every bit as destructive as a fit of anger. When we turn our backs on the suffering of our neighbors, we turn our backs on God. Restaurant workers move around a lot, and Alberto and I lost touch. Eventually, I got a job as a workplace justice organizer with the Restaurant Opportunities Center of New York. ROC-NY, as it’s called, was formed in 2001 to help restaurant workers displaced by the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center and has grown to become a national organization in ten urban centers that organizes workers to fight against illegal practices and bad policies in the restaurant industry. As workplace organizers it was the job of our team to start a justice campaign in a fine-dining restaurant group that was treating its workers illegally—discrimination, sexual harassment, stealing tips and wages, that kind of stuff. Celebrity chef Mario Batali and his numerous NYC restaurants had a bad reputation in the industry for all of these things. Batali’s reputation hasn’t gotten any better recently. He was forced to step away from his businesses after the Me Too movement caught up with him. But we were hearing stories of his sexual harassment way back in 2009. And management was stealing tips, creating a hostile environment for workers of color and immigrant workers, and they were discriminating based on race in their hiring and promotions. We met with a lot of angry workers. One of the reasons our campaign succeeded was because I found my old coworker Alberto working as a busser in one of Batali’s restaurants. You can imagine that, at first, he did not want to get involved—he was shy. But he was also angry. His managers had insulted him, called him racist names, and even put their hands on him—threatening and demeaning him. The launch of the campaign was especially stressful for the workers. We told them we couldn’t just file the paperwork in court, but that they needed to present their demand letter to their manager at the restaurant in person. And that it would be a big, public event. All the workers would be there. We’d have a big group of allies and supporters. We’d have news reporters and filmmakers. More than 100 of us would march together to the restaurant during dinner service, go inside, ask to see the manager, and one of the workers would hand the demand letter to their manager and in the biggest, loudest voice they could muster, so that everyone could hear, they would summarize the list of complaints and demands to their own manager. Obviously, no one really wanted to be the spokesperson of the campaign. No one wants to single themselves out as a leader, or a rabble-rouser, because they were afraid of retaliation, of losing their jobs, of the police, and of immigration troubles. In the end, there were a lot of workers who talked a lot in meetings who passed on this opportunity. But it didn’t take long for Alberto, who was always quiet, and who never wanted trouble, and who struggled with pronunciation, and who was embarrassed by his English, to raise his hand and volunteer. Anger was moving Alberto. This wasn’t like beating up on himself for messing up an English word. There was a fire in Alberto and it was changing him. He wanted to put himself out front, out in front of all his fears. He found himself wanting to stand up for himself and people like him, to affirm himself in the face of disrespect, in spite of all his fears and the very real risks of leadership. This was strength, this was guts, this self-respect. And anger was the seed that (with the right care and motivation and direction) that eventually produced this harvest of heroism. And, beloved, when the moment came, Alberto was great. He lifted his head up and squared his shoulders. Flashing cameras popped around him. He looked his manager in the eye. The crowd hushed. He spoke slowly, loudly, clearly about the abuses the workers had suffered and what their demands were. And everyone heard him. Right from the launch of this years-long campaign, Alberto looked his fear right in the eye and said as loud as anyone ever has, “Here I am.” This was anger as I had never seen it before—not immature, not violent, not destructive, but the opposite. It was brave, it was persistent, it was the emotion of self-worth, it was a compassionate force that was building something—a campaign for justice. I still worry about anger. But, you know, everybody gets angry. What do you get angry about? What do you do when get angry? Has your anger ever made the world a better place? Has anyone ever had a reason to thank God for your compassionate anger? Beloved, it’s fine to worry about the destructive kind of anger, but let’s not miss the opportunity to allow anger to move us toward something greater. Preaching on: Matthew 25:31–46 Today is Amistad Sunday in the United Church of Christ. I wouldn’t be too surprised if some of you don’t know the story of the Amistad or, if you do, why do we celebrate it as a special Sunday in the UCC. I’m going to tell you some of that story today because it’s one of the most important stories in the history of our country and in the history of the UCC. It’s so important to our denomination that it defines the ways that we think about our mission, our calling from God, and how we define our ultimate concerns as the followers of Jesus. So much so that we’re going to have to get into the question raised so powerfully by our reading this morning—what is the substance and character of salvation?

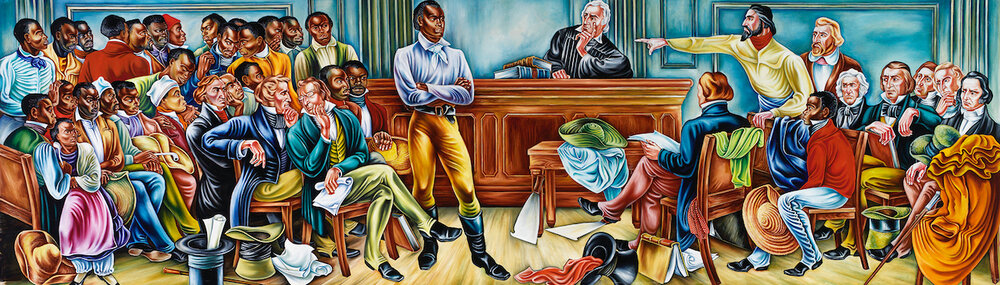

When our Congregational ancestors, the Pilgrims and the Puritans, first began arriving in the New World in 1620, it was more than year after the first African captives were sold as slaves in Virginia. That fact always strikes me. We sometimes mythologize the Pilgrims as the beginning of America. But for more than a year before they landed at Plymouth Rock there were Black people enslaved in the tobacco fields of Virginia. This is also our national origin. We know that a small group of Congregational Pilgrims came to the New World to escape religious persecution in England. But the much larger waves of Congregational Puritans who arrived after them had a different purpose. That purpose was stated best by John Winthrop. He said, “We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” What he meant by that was that their colony was going to be a perfect Christian society, a vision of the Kingdom of God so powerful that it would reform and purify the values of England from across the ocean, and all of Europe would be transformed by the light of their righteousness. In the earliest spiritual DNA of our Congregational ancestors there was a desire for a social transformation on the earth, in this life, that knew no boundaries. This was one of their ultimate and motivating concerns as Christians. It was their calling from God. How did it go? Not so great. Slaves were brought to Massachusetts in 1630. Slavery was fully sanctioned in the early 1640s. Then from 1675 to 1678 one of the most brutal wars in American history took place between the Puritans and the Wampanoag and the Narragansett Native Americans. The Wampanoags were the very same people who had kept the Pilgrims alive through their first difficult years. But by the end of the war both tribes were nearly destroyed, and they were left practically landless. The Puritans wiped them out with a Biblical meticulousness—men, women, and children, whole villages gone, two nations nearly eradicated. The Puritans’ desire to transform the world was a Godly desire. Their methods were the worst kind of depraved, antichrist sinfulness. New generations of Puritans were being born in the New World. They had never seen England and never would. They would never even see picture of the place. It might as well have been on the moon. They didn’t care about it. Europe? What’s that? They weren’t interested in purifying any of these storybook places. They had New World problems. So later generations turned away from their parents’ ideals and convictions and turned their Puritanism away from the world and directed it all inward. Their ultimate concern was now the sins of individual soul and individual virtues: propriety, hard work, temperance, and prudence. Puritanism was done and we became better known as the Congregational Churches. That’s our origin—big worldly ideals reduced down to individual piety. And that’s kinda the way it went for a while. Fast forward to 1839 when Portuguese slavers illegally capture hundreds of Mende people in Sierra Leone, sail them through the Middle Passage to the Spanish colony of Cuba, and sell them into slavery. 53 of these Mende people were then being transported to a Spanish plantation aboard the ship La Amistad. Fearing for their lives, a young Mende leader named Singbe Pieh frees himself and others from their chains, they arm themselves with knives, and take control of the ship. They demand the crew sail them back east to Africa, but during the night the crew sails them west and they are eventually overtaken by a US Naval Ship. The Mendes were taken prisoner again (as pirates) and transported to New Haven, CT where a battle ensued over whose property they were. Were they the property of the US naval officers who claimed them as salvage, or were they the property of the Spanish plantation owners who bought them, or were they property of Queen Elizabeth II of Spain who owned La Amistad? President Van Buren wanted good relations with Spain and demanded the prisoners be handed over to the Spanish government as quickly as possible. But a group of abolitionists and Congregationalists had formed the Amistad Committee to raise money and organize people for the prisoners’ defense. They believed that the Mendes were legally free and not slaves because they had been illegally captured in Africa and not born into slavery (the transatlantic slave trade was illegal at this time). The case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Former president John Quincy Adams argued in defense of the prisoners and the court found that they were not slaves or pirates, they were legally free people who had every right to fight for their freedom. Singbe Pieh pleaded during the trial, “All we want is make us free.” Now they were free at last. But the work of the Amistad Committee was just getting started. They now had to fight to return the freed Mendes to Africa. In the meantime, the Mendes lived in New Haven, stayed in the homes of church members, and attended worship with them until 1841 when funding was finally secured, and they sailed home. The story of the Mende captives struggling for life and freedom and the opportunity to stand by them in their defense reawakened a sense of spiritual purpose in the Congregational Churches. Personal piety was being transformed again into a new movement for transformation. God was doing something new. The Amistad Committee joined with other abolitionist and multi-ethnic groups across the country in 1846 to form the American Missionary Association. It was the first abolitionist missionary society in the United States, and it was a driving force for abolition and later for equal rights and education for Black people. During Reconstruction more than 500 schools were established for the education of freed slaves, including 11 historically black colleges, many still operating today. And in 1999 the American Missionary Association became the Justice and Witness Ministries of the United Church of Christ which continues to advocate and organize for human rights, women’s rights, racial justice, and economic justice. And we continue to support that work through special offerings, like the Neighbors in Need offering we collect in October and through our church’s annual giving to the national UCC which is overseen by our own Ministry of Outreach & Mission. Now, ever since 1839, the Amistad Committee, and then the American Missionary Association after it, and today our Justice and Witness Ministries and the UCC in general have received criticism from those who believe that “social justice” should not be one of the ultimate concerns of Christians. Salvation should be the only ultimate concern of Christians. Whether or not there is justice and equity and fairness in this world is a distraction from the salvation of the individual soul, and it’s a distraction from spreading the message of the good news of Jesus Christ. In 1839 there were many who called themselves Christians who were convinced of this. There were slaves in the Old Testament, after all. There were slaves in Jesus’ day. There were slaves in Paul’s day and in the early Church. God doesn’t care whether you’re a slave or not in this world, God only cares that you accept your lot in life, carry your cross, and get saved. It’s not about the conditions of the external world. All that matters is the condition of your eternal soul. But then we read again what Jesus says at the end of Matthew’s gospel: For I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me… Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not take care of you? …Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me. And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life. And when we hear those words, we must realize that we cannot separate individual spiritual salvation from social justice for everybody. Put it another way—there is nothing, nothing in the whole world, no power, or oppression, or injustice that can separate any person from God’s love. And there is nothing that could ever stop an enslaved person (for example) from being saved by God. But the person who looks upon their suffering and distress and does nothing? The person who trivializes their oppression as beneath God’s concern? The person who can’t be bothered with all that drama and anger and can’t we all just get along? The person who refuses to bow, refuses to listen? The person who cannot cobble together the courage to look the hard truth in the eyes and to respond? What about them? Are they saved? Will they be saved? Let’s just say that in our scripture reading this morning Jesus offers us an unambiguous and urgent word of warning. I think that our spiritual ancestors’ experience with the Amistad Committee, helped them to see that Jesus’ call to “do unto the least of these” is not merely a call to individual acts of charity. It reconnected them to that powerful calling in their own spiritual ancestors to transform the world. But this time instead of war, they would make peace. Instead of bloodshed, justice. Not because the transformation of the world is salvation. But because without giving ourselves to the needs of the least of these, Jesus seems to say that we cannot truly give ourselves to him. I think for the Amistad Committee, for the American Missionary Association, and for much of the United Church of Christ today, transforming the world, making justice, fighting for freedom is about walking the walk of salvation. It is the only possible response to the freedom we receive in grace, to the mercy we receive in forgiveness, to love we receive in Christ, to the revolution of values that Jesus teaches us. And if we cannot find it in our hearts to respond to God’s love with love for our neighbors and to respond to God’s grace with justice for all, we are in spiritual danger of cutting ourselves off from God. If we trivialize our neighbor’s hardship, we trivialize God’s goodness. If we shrug off our neighbor’s suffering, we turn our backs on Jesus. Beloved, the good news is that our Church, the United Church of Christ, the UCC, has been fighting for racial justice for hundreds of years. We know how to do this. We have the resources. We know we’re not there yet. And we know that we are called to transform our world and our church into a vision of the Kingdom of God. Singbe Pieh said, “All we want is make us free.” Maybe we will only ever find true freedom when we answer God’s call to transform our world with love and justice. Preaching on: Mark 8:31–38 In early September last year my mom, Roberta Mansfield, was in the hospital. She’d gone to the hospital for her chemotherapy (my father practically had to carry her in), and once the staff saw how sick she was—the cancer was bad, the therapy had been brutal, and her body was just shutting down—and once the hospital staff saw how bad she was, they skipped the treatment and just admitted her.

My mom’s cancer doctors and nurses were always very positive. I guess they feel like they have to be because you never know for sure what someone’s outcome is going to be. And who wants to give someone bad news? They told my mom she would be in for just a few days until they got this and that sorted out and then she’d have her treatment and go home. Nothing to worry about, they told her and my dad. If I was a doctor or a nurse, I think I’d have a hard time telling people that there was nothing to worry about—just a few days. Because I’d always want to tell people the truth. This is a problem I have. When my time is up, I want to know. I want a doctor who’ll look me right in the eyes and say, “Mr. Mansfield, of course I don’t know for sure, but I think this is probably the end of line. There’s nothing left that we can do. I’d guess you’ve got a couple weeks left at most before you die. I’m so sorry.” I can think of no greater kindness to give someone at the end of their life than that. I would be eternally grateful for that honest message and for the courage it took to deliver it. By the time I got up to Rhode Island to visit my mom she had already been in the hospital for a week with no release in sight. I’ll never forget that night I spent talking to Mom in the hospital—how tired she was, the discomfort she was felling, how she would just look me right in the eye without saying a word for a minute or more. I had never seen her do that before—just look at me like that. At some point I realized: this is what fear looks like when the person feeling it is too tired to move. I’ll never forget how Mom eventually told me that she thought she’d be better off at home, released from the hospital, and in hospice. I’ll never forget the courage it must have taken to tell her little boy that she couldn’t go on and that she “wanted” to die. Of course, part of me wanted to yell, “But you can’t die! You’re my Mom! I need you.” I don’t know. Maybe it was because of Peter that I knew I couldn’t say that. Instead, I said, “Mom, when your doctor comes in tomorrow, you look him right in the eye and you tell him, ‘Doctor, I think this is probably the end of line for me. I don’t want any more treatments. I’d like to go home and be put on hospice. Is there any reason that you can see that we shouldn’t do that today?’” The next morning that’s what Mom did, and she was back home that night. I have a lot of reasons to be proud of my mom, but right there at the end she made me so proud again. She took control of her death. She wasn’t happy about it. She wasn’t unafraid. But she knew it was inevitable, that there was nothing anyone could do. She knew she was going die and she told us so. She told me and the rest of the family. She told her doctor. She told hospice. And we all supported her in her courageous final days. She died at home 12 days after being released from the hospital. In 1921, Karle Wilson Baker published a poem called Courage that would be the stuff of motivational posters’ dreams for generations to come. The brilliant closing lines of the poem are these: “Courage is Fear / That has said its prayers.” I always thought that was a great line. But then I saw my mom actually make that line come to life. And I realized because of my mom how true it is that you can’t really be brave without being afraid. Courage is the transfiguration of fear, not the absence of it, not the banishment of it. One thing I have in common with doctors and nurses is that I think a lot of people want to be comforted by healthcare professionals—we call it a good bedside manner. And, of course, people want their pastor to be a source of comfort to them as well. And I think when we think of comfort, we think of saying things like, “You know my cousin’s wife had cancer and she took the chemotherapy, and she was fine.” We think of the doctor smiling and the nurse patting our hand and saying, “Just a few days—nothing to worry about.” Maybe that’s all that Peter was trying to do—to say to Jesus, “Don’t say that! You don’t know for sure what’s going to happen! My auntie got detained in Jerusalem once for giving a legionary a sour look, but nobody crucified her, did they?” Maybe he was just trying to be positive—I’m sure it will all work out! But I’ve realized that there’s another kind of comfort as well. The comfort that looks you right in the eye and tells you the truth with kindness and love. My mom’s most experienced hospice nurses demonstrated this to us. They came into the house like it was a house where someone was dying. They looked at you like they were looking at someone who was about to see his mom die. They spoke to Mom like you speak to someone who’s dying. Not with pity. Not with false hope. But with respect and honesty—and with an awareness that they’re in a sacred space. It’s like they know that they’ll have forgotten your face within a few weeks of the death, but they also know that you’ll remember them forever. When we seemed like we were thinking a little too optimistically, they helped gently steer us back to making decisions more aligned with Mom’s reality. When we worried about giving Mom more morphine than she needed, they told us the truth, “You have nothing to worry about.” It was comforting to be told the truth. Just like my mom told the truth, just like the hospice nurses told the truth, maybe that’s all Jesus was trying to do. Maybe he was trying to prepare the disciples for what was coming. He didn’t want them taken by surprise. He owed them that respect. He knew he couldn’t enact the Kingdom of God on earth forever without the powers of the Kingdoms and Empires of this world killing him for it. He just wanted to tell them the truth. It must have been hard to do. One of our themes this Lent is Lent of Liberation: Confronting the Legacy of American Slavery. I’m reading a Lenten devotional by that name and you all are invited to join with me in reading and discussing the text this Lent. Our first discussion is this evening at 7:30, there’s an announcement in your bulletin with the details. Last week I told you that if we’re going to hear another person’s truth, especially if their perspective is different than ours, it requires us to cultivate humility—to bow low before God and to admit that we don’t know everything; to bow low before our neighbors, low enough to consider their truth, their perspective. It does take humility to have a difficult conversation. It takes humility to see things from a different perspective. And it takes courage to tell the truth to someone you know would probably really rather not hear such uncomfortable truths. And it takes courage to accept a truth that maybe makes you angry, or makes you feel guilty, or annoyed, or maybe breaks your heart. In these types of situations, we see the limitations of comfort. Comfort can’t fix a broken thing. Sometimes the truth can’t either, of course. But at least the truth looks you in the eye. At least the truth knows it’s standing on sacred ground. At least the truth is willing to pick up its cross and carry it as far as it can. And there is comfort in that. I doubt a comforting lie ever empowered anyone to take up their cross. I think only the comforting truth can do that. “Courage is fear that has said its prayers.” Why did Jesus have to die? I don’t really know. Why did my mom have to die? I don’t know. But when she told me the truth, I believed her. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed