|

It’s Trinity Sunday, which is the one Sunday in the church year that the calendar instructs us to focus on a doctrine of the Church—The Trinity, God in Three Persons (Father, Son, Holy Spirit; Creator, Christ, Holy Ghost), each “person” distinct but also all coequal, coeternal, and consubstantial. It is a distinctive Christian doctrine (no other religion has anything quite like it). For that reason, perhaps, it is also sometimes confusing to people—it has certainly been fought over! And it is also beautiful, if you just let yourself take in the view that the Trinity presents to us. It’s a beautiful thing. And I think it reflects to us something true and beautiful about who we are as people created in the image and likeness of God.

We have at home a very active 20-month-old little boy, Romey, and we don’t let him watch a lot of TV, but when we do it’s often dance videos on YouTube. I’m not much of a dancer, myself, but Romey loves to dance, and we’ve got to keep him moving to burn calories and get some sleep. I don’t have to be too self-conscious about my dancing in front of a toddler, and he’s actually taught me one thing that the dance videos couldn’t teach me and that’s the key is really to just keep moving. We’ve got to keep moving. And we see this in children: We were made to keep moving, to keep learning, to keep drawing the world into ourselves so that we can become a meaningful part of the world. Sometimes we rush through life, we overschedule ourselves, we never stop to smell the roses, and we burn ourselves out. That’s not what we’re talking about here, we’re talking about dancing—about moving toward the heart of the party, jumping in with both feet, a sort of celebratory commitment. Dancing is not about living frantically; it’s about living joyfully. We’ve got to keep moving with joy. We don’t want to get stuck without it. There’s an old Greek word for this, perichoresis, which literally means “to dance around.” And the word was used in the early Church to describe the Trinity. You can see this picture in your head, if you try, right? God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit in twirling, dancing relationship to one another. In the dance, each “person” of the Trinity is fully related to and in no way separated from the other two. It’s one dance they’re dancing. But it’s not a melting pot. It doesn’t eat up the individuality of the dance partners. Instead, the perichoresis is a living relationship between the Parent, the Christ, and the Spirit forever moving and dancing with one another, fully interconnected, yet individually intact. When take in this beautiful view of the Trinity, we see that in the very nature of God, stuckness is nowhere to be found. Joylessness is an impossibility. Dancing and jubilation and activity are at the very heart of God’s existence. Let’s keep this view in mind as we turn to Isaiah and Nicodemus this morning. Both Isaiah and Nicodemus are at the beginning of something. And I’m interested in this because, I think, so are we. Again, right? Here we are—again—confronting a new reality—we’re now reopening our sanctuary to the public for worship on July 11 and we’re contemplating the best ways for us to do ministry in this new moment we’re now in. The question I have for us is “Where might we be stuck? And what is moving us forward with joy?” And with both Nicodemus and Isaiah we see this in their beginnings—a mixture of hesitation and recommitment. When we begin something new, we begin from what 20th Century comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell calls “The Ordinary World.” We know what that is. It’s the world we live in when we’re not on an adventure doing something new. Isaiah was living in the ordinary world of Judah during the reign of King Uzziah. Times were difficult, and he saw no path to becoming a person who could make a difference. He was stuck. Nicodemus was a respected pharisee, teacher, and member of the Sanhedrin council who dedicated himself to a particular way of life and to keeping a particular order to the world. He was not a man of doubts. He was comfortable, assured set in his ways. Young or old, privileged or oppressed, paradise or dystopia, we all know what it feels like to start somewhere—the place we are before God speaks or before God strikes, as the case may be. Into the everyday life of the ordinary world comes the Call. Isaiah is suddenly caught up in a vision of God almighty upon a throne. God’s voice calls out, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” Nicodemus for the first time in years finds himself unable to sleep, restless, bothered—bothered by that wild rabbi, Jesus, and his teachings. He goes to see Jesus at night. He wants, I think, to settle himself down, to stop the questions and the turmoil in his heart. He wants to go back to sleep! But that’s not what Jesus offers him, instead Jesus invites him, an old man, to be born anew. The call wasn’t easy for either Isaiah or Nicodemus. That’s because God doesn’t have to call us to do easy things or to commit ourselves to no brainers. Every call is a call to adventure and a call to loss. So much so that even tragic news can turn out to be a call. My mom’s cancer diagnosis in 2019 turned out to be the call to complete her life. And it was hard, and there was meaning and purpose in. The call is always a call into a spiritually bigger kind of life, a life in which we push at the boundaries of the Ordinary World, push our vocations, push our families, push our comfort, push our diagnoses, in which we scramble up the DNA of the Ordinary World to try to make a new world, a better world for ourselves and for others. And that is always hard. And so before we can accept the Call, here comes what I think is the most important part of a new adventure. It’s the place where we get stuck. After the magic or excitement or horror of that initial call has worn off, we can get stuck in between the ordinary world and the world of new possibilities. Joseph Campbell calls that stuckness “The Refusal of the Call.” Refusal. Well, that sounds a little judgey, doesn’t it? Because, I mean, aren’t there sometimes outside forces—forces that we have no control over—that hold us back? What Campbell understands is that a necessary component of answering a call is a time of doubt where, perhaps overcome by obstacles, we say NO. In other words, doubt and the acceptance of doubt are built into the very beginning of every spiritual journey. Why do we refuse the call? Well, we start out with practical excuses. We can’t leave the farm before the harvest. We have fields and commitments, family, responsibility. The journey is too long, too difficult, too expensive, too dangerous. And when we’ve finally burned through every external excuse for not moving forward, we come down eventually to the real, fundamental, core issue: “I’m just not good enough.” Our initial doubts may be external, but our final doubts—the doubts that really must be contended with—are internal. In a wonderful line that’s always stuck with me, Harry Potter says, “I can’t be a wizard; I’m just Harry.” Isaiah says, “Woe is me! I am lost, for I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips; yet my eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts!” Nicodemus says, “How can anyone be born again after having grown old?” I don’t have what it takes to start God’s adventure again. I’m just not good enough. In Joseph Campbell’s writings he talks about how in the myths of the Hero’s Journey the hero is judged based upon their heroic return to the ordinary world to give back to the people what they have stolen from the gods or whatever. You’re not a hero because you receive the call. You receive the call precisely because something is lacking. God calls those who are missing something to be the ones who find what is missing. So, the Refusal of the Call is a necessary part of the journey because after all the other excuses are cleared away, we are left standing in the presence of God, looking into the mirror and realizing, “There’s something missing!” The person who doesn’t have that experience, might think that they were chosen because they’re perfect and that they’re expected to be perfect in everything they do. The person who doesn’t have that experience might go out into the world thinking that are being called to win, when actually God is calling us to grow. That’s how God works. She gives important work to imperfect people. Sometimes certain people realize that if they just keep messing things up, eventually people will stop asking them to do things. We’ve all known somebody like this. But our Triune God never gets stuck, she just keeps on moving. Even when we want nothing more than to be left alone, God doesn’t ever give up on us. You are not perfect. I am not perfect. Neither is our church. No matter. A change is coming, a call to a new adventure, to the world’s next great need, and God is wondering who to send. Beloved, if there was ever a time to do things differently, if there was ever a time to let go of the things that may have been slipping away already, if there was ever a time to lean into new opportunities, events, and ministries, now is the time. The world is wounded, our neighbors are seeking, we are called, and God is dancing, dancing all around—dancing, dancing, dancing.

0 Comments

Preaching on: Acts 2:1–21 In the late 90s I worked at a summer camp way out in the woods in North Carolina. One night after a closing Bible study in an old army tent with my campers we switched off our flashlights and fell asleep in the quiet dark. Around midnight I was awoken by a sound like I had never heard before—a wild yipping, yapping, growling chorus echoing through the woods and getting louder and louder, louder and louder until this pack of coyotes was rushing like a tornado right through our campsite. I’ll never forget sitting there on my cot, my heart pounding, adrenaline coursing through me, my imagination running wild as I listened to them scampering, sniffing, howling, and tearing at one another just on the other side of the tent wall—feet away from me.

I wasn’t afraid of them—I knew we were safe in the tent, but they awakened some slumbering part of me. I wanted to step out of the safety of the tent, I wanted to howl back at them, I wanted to run with them through the woods. I realized that while I had many things that coyotes do not have, those coyotes still had something themselves that I was wanting. Maybe something I was not even able to comprehend. What was it? The great French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil once wrote, “We know by means of our intelligence that what the intelligence does not comprehend is more real than what it does comprehend.” That’s a Pentecost statement, I think, because Pentecost is about broadening the idea of what intelligent comprehension is. Intelligent comprehension is not just spread sheets and flow charts and facts and rational answers. There is another form of communication, one which we’re all capable of speaking in, and it’s not a barbaric language, not just the howlings of a drunken mob, not the “tale told by an idiot” that faith is often made out to be. The Spirit has its own intelligence that even we Christians are sometimes regrettably alienated from. Now, why is that? Are we afraid that if we go out to “run with the wolves” we have more to lose than to gain? Are we afraid that we’ll look drunk or foolish or that we’ll be scorned? We’re suspicious of the intelligence of the Spirit and the language she speaks, I think. The intelligence of the Spirit is hot, hopeful, loose, faithful, wild, and wise. Can you even imagine such words being listed together as if they belonged to one another? Hot and hopeful? Loose and faithful? Wild and wise? The intelligence of Pentecost says YES to such unlikely pairings because Pentecost does not see any animosity between that which is virtuous and that which is exciting, between that which is rational and that which overflows the dams of rationality. Within us, within all of us and within each of us, and within the universe itself there is a deep reservoir of spiritual intelligence that doesn’t do arithmetic, doesn’t exist to fill in the circles on a multiple-choice test, is not held back by what it has been told is known and what it has been told is possible. It does not hold to the rules and restrictions of the grammar of rationality—and yet it is intelligent and intelligible. It is an intelligence that is drawn to the Mysteries that cannot be proved, but which are useful and powerful precisely because they cannot be proved. You cannot prove that life is worthwhile. It is an untestable theory. And if you are a person who cannot decipher the natural intelligence of the Spirit, if you are someone who cannot be inspired to hope in times of despair, to faith in the age of reason, and to love in a culture of contempt—then no matter how great your achievements may be they will feel empty because no one will be able to prove that they are meaningful, no one will be able to prove that they are anything more than the predetermined accidents of an empty existence in a meaningless universe. And so through the intelligence of the Spirit we are inspired to become a people not of certainty, but of conviction. The intelligence of the Spirit longs to look out on the vistas of the great questions in life and never wants the view to the far horizon to be blocked off by an answer, by a dogma, or even by a reasonable interpretation offered too early or too eagerly. God goes all the way to the horizon! And how often we try to hem God in and make God logical and dry and conventional. But by the intelligence of the Spirit we learn how to step out of the way, how to inspire, and how to be inspired by the view that is beyond us. I mean, My God! Look at what happened on Pentecost! There was fire in the air! Everybody thought they were drunk! They were speaking languages they shouldn’t have known! And a bit after where our reading ended this morning, we are told that after witnessing the events of Pentecost morning more than 3,000 people were baptized! What was it that moved them to give themselves over to God’s Spirit so completely? Was it decorum? Was it tradition? Was it some creed? Was it an answer at the back of the coursebook? No, no, no, no. It was the intelligent, palpable, wild heat of that morning. It was the men, the women, the people who let themselves be moved by it, who let the speech of their tongues, the hearing of their ears, and the intelligences of their hearts be transformed by it. The outpouring of the Holy Spirit in our lives, in our church, must be experienced at levels deeper than what the rational mind can comprehend. Max Weber, one of the founders of modern sociology, defined three kinds of legitimate authority: traditional, rational, and charismatic. Traditional authority is upheld by doing things the way they have always been done according to custom. Rational authority is upheld by doing things according to the rules, following the proper procedures. Charismatic authority is based upon the power of personality—connecting deeply to the emotions, the desires, and the soul of the people. Weber said that the most unstable form of authority was charismatic authority because charismatic authority dies when the source of the charisma (the charismatic leader) dies, or the power is maintained but only by transforming charismatic authority into something else—into tradition or rationality. And this, I think, is what has largely happened to the churches and to Pentecost. The birth of the Church was a charismatic miracle of the Holy Spirit. Many of the earliest Christians were drawn into the church because of the way that the Holy Spirit was allowed the freedom to connect them spiritually and viscerally to God and to their neighbors. But slowly that miracle was transformed from an ecstatic, heart-pounding, communal encounter with God’s Spirit into something much tamer, something much more staid, something much more reasonable. We’ve turned it into a story about church history, rather than living it out as the example of who we are and what we do in church today. We have forgotten that our charismatic leader is not dead, is not gone. The Holy Spirit is still here, still working among us. WE are the charismatic leaders of the church of today and tomorrow—that’s the invitation of Pentecost to the Church in all ages. Of course, churches have traditions, and they should. Of course, churches have bylaws and politics and theologies and interpretations and explanations, as they must. But our traditions and our rules and our expectations have always been meant to recreate the opportunity for the world to have a charismatic, Holy Spirit encounter with the power of the resurrected Christ and the living God. Beloved, in church it’s not supposed to be Christmas all the time, it’s not supposed to be Easter every Sunday, but every day ought to be a little like Pentecost. Instead, the outpouring of the Holy Spirit has been domesticated by the churches, and it is up to us to reintroduce ourselves to the wild. Pentecost is the birth of the Church and the model for what the churches ought to be—and the story of Pentecost makes clear we’re meant to be more Dionysian than Apollonian, more tent revival than chapel, more Burning Man than country club. The Holy Spirit is a special kind of chemistry between people, between God and us, between the Church and the world, and heat is the key ingredient to the chemical reaction we are hoping to incite. We need fire. And how many of us can say that we have been set ablaze by the Holy Spirit and that the flames are spreading to the four corners of the globe? The poet Rumi advises us on this point, “Do not feel lonely, the entire universe is inside you. Stop acting so small. You are the universe in ecstatic motion. Set your life on fire. Seek those who fan your flames.” So, this Sunday, Pentecost Sunday is not a Sunday to be rational, circumspect, or decorous. It is not a Sunday for easy answers or for seeking salvation solely in the experiences of our spiritual forebears. Of this I am sure: meaning cannot be found in answers given to us or in experiences unlived by us. Meaning can only be found in wrestling with convictions, with community, with suffering, and with love. When it comes to meaning, answers are just placeholders—the finger pointing to the moon. This is the other virtue of Weil’s words, “We know by means of our intelligence that what the intelligence does not comprehend is more real than what it does comprehend.” Not only do her words encourage us to broaden our intelligence, they also decenter us and remind us that that which is most real, most important is beyond us—and if we’re smart and if we’re humble, we’ll pay attention to what is most real—that intelligence which leads us first to grace and then to fire. Our scripture reading this morning is from John’s Gospel, chapter 17. You’ll need a little context to pick up where we are here. Our reading is a portion of what’s come to be known as Jesus’ “High Priestly Prayer” or his “Farewell Prayer.” This prayer only appears in John’s Gospel. Jesus prays it at the end of the Last Supper just before he and the disciples depart for the garden where Jesus will be betrayed and arrested. So, that’s where we are in the narrative this morning—the closing prayer of the Last Supper. This prayer (like you might expect from John’s Gospel) is long, and it has three thematic sections. The way the Revised Common Lectionary works is that we read section 1 in Year A, section 2 in Year B, and section 3 in Year C. This is Year B, so we’ll be hearing the middle bit of the prayer this morning. In section 1, Jesus opens the prayer by praying for himself and he asks to be glorified so that the world might come to believe. Section 3 is where Jesus famously prays for all future believers “that they may all be one.” Here in the middle, in section 2, Jesus is praying for his disciples—as they listen to him—so it’s Jesus’ final words to them before his death, and by extension his closing words to all of us who desire to follow Jesus and to be his disciples. Preaching on: John 17:6–19 A staple of Christian education is the old saying, “We are in the world, but not of the world.” You’ve probably heard it before, right? It’s not an exact quote from the Bible, but a teaching tool interpreting what scripture is saying in certain places. “We are in the world, but not of the world.” The major source of this rhetorical device is right from our reading this morning, and you can find other materials in the other gospels, in the letters of Paul, and other New Testament books that bolster this sentiment.

“We are in the world, but not of it.” I’m not a big fan of this saying. I know you’re not surprised to hear me arguing with tradition. And I can’t say that this statement isn’t true. But I think it’s a misleading and inadequate interpretation of what the Christian disciple’s relationship should actually be to the world. So, we’re going to discuss what’s true about “We are in the world, but not of it,” and we’ll talk about where some of the problems come in. And then we’re going to talk about the shift in perspective that I believe ultimately requires a Christian disciple to leave this formulation behind and to grow into a more ultimate truth. Let’s start with a story: It’s the last week of Jesus’ life. He’s teaching in the Temple in Jerusalem. Some people come to him and they ask him, “Should we pay taxes to Rome or not?” Jesus asks for a coin. “Whose picture is on this coin?” he asks. “Whose inscription?” The people say, “Caesar’s.” And Jesus responds, “Then give to Caesar that which belongs to Caesar, and give to God that which belongs to God.” Now, I’d say that the most common interpretation of this story is that you’ve got to pay your taxes and you’ve got to follow your government’s laws. This is the “Render unto Caesar” interpretation which conveniently forgets that that’s only one quarter of what Jesus actually said. What Jesus actually said was, “Render unto Caesar that which belongs to Caesar, and give to God that which belongs to God.” Jesus doesn’t say “pay” or “don’t pay,” because “pay,” I think, wouldn’t have fully represented his position and “don’t pay” would have had him immediately hanging on a Roman cross, and he needed a little more time. Instead, Jesus presents all of us with a higher order of discernment: We must determine what belongs to Caesar (or what belongs to the world) and what belongs to God. What I think we can all agree on is this: that we live in a world ruled by Caesars and empires, but we do not belong to Caesar, to Rome, to sin, to injustice, or to death. We are in the world, but we are not of the world. We heed a different call, we worship only God, and we are guided by Jesus’ surprising, challenging, unworldly values. Now the problem comes in, in part, because the word “world” is a very general word. Even in the original Greek, kosmos, it can mean a lot of different things—it’s a big tent. What do we mean by “the world”? Where is the likeness of the world imprinted? And where is God’s likeness imprinted? And are they always mutually exclusive? From the Gospel according to John chapter 1: The Word was in the world, and the world came into being through the Word. The whole world, all things, came into being through the Word, through Christ. So, for example, do nature, the environment, the ecosystems, and planet Earth—do they belong to God? Or is all that “stuff” just the world, the place we are not of, the place we don’t truly belong? Christians disagree on this. Some say that God will redeem all of Creation. Some say we are commanded to be good stewards of God’s Earth today and to the end of time. Others say that Creation must be destroyed for the final judgment to happen and so who cares what happens to the world today? What parts of Creation are just “the world” and what still belongs to the God who made it all in Christ? Where do we draw the line? Can we draw a line? From John 3:16: For God so loved the world that God gave God’s only son. Is it just Christians who belong to God and the rest of the world are a bunch of lost sinners—the kind that Noah’s Ark leaves behind to drown? Or are all people created in the likeness and image of God, and, therefore, all people belong to God and to nothing else? Humanity in general has certainly not yet made up its mind about who’s in and who’s out, who’s deserving and who’s unworthy. We would hope that Christians would see all people as equally made and equally beloved, equally belonging to God, but it doesn’t always go that way. So, it’s indisputably true: We are in the world. No one really denies that, as much as we might have wanted to over the last 14 months. Here we are. That’s true. And we are not of the world. That’s also true. We do not belong to Caesar, we do not belong to Pharaoh, and we render unto God. But this particular formulation (almost like a creed), “In the world, but not of it,” tempts us to be pessimistic and judgmental about the world and its inhabitants. It tempts us to believe that we are merely strangers in this place, just passing through—that the world doesn’t really matter, that the planet or that people different than us are just in the way somehow. So, the question we must ask ourselves as Christians, who hold with the idea that we are in the world, but not of it, is this: Are we Christians less committed to the world and its people than others? And I think the way this old staple is strung together (in the world, but not of it), it’s tempting to deny our responsibility to the world and to our neighbors. There are some truths which are more reliably true than others. And the truths that are most true will point us unfailingly in the right direction, headed toward our final goal. “In the world, but not of it,” cannot be an ultimate Christian formulation defining our relationship to the world because it lacks any kind of missional aspect. In fact, it can lead us away from the idea that we have a mission in the world at all. And how can you be a Christian without a mission? How can we be a church without a mission? “In the world, but not of it,” seems to say that my being here in the world is just an accident. It just happens to be the lousy place I unfortunately find myself. And my job is to not let myself be tainted by the world too much, not to get too attached, so that when I die, I can float off to heaven unencumbered by this place and my time here. But isn’t the very receipt of God’s grace in our lives simultaneously a call to action for us, a call to sacrifice, and a call to great expectations? Jesus said, “From everyone to whom much has been given, much will be required; and from the one to whom much has been entrusted, even more will be demanded.” Listen again to the closing verses of our reading this morning, Jesus said, “They do not belong to the world, just as I do not belong to the world…” That’s not a mission. That’s just a statement of fact: We belong to God. Then Jesus says, “As you have sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world.” Because much is expected of us and because a church must always be an organization with a clearly defined mission in the world, I think we need to turn this old saying around and redefine it. Instead of “In the world, but not of it,” I propose we say it this way: “Not of the world, but sent into it.” Better yet, let’s try this: “We belong to God, and God is sending us into the world.” We are not of the world because we know that we belong to God alone (that’s where we begin), but precisely because of the grace we have received which has revealed the truth to us, we are being sent into the world to love it and to serve it without holding anything back—as if it were our very own. We’re even called to lay down our lives for one another—to serve and to love with a commitment that isn’t decreased by faith, but that’s made greater by it. That’s a mission! That is the end we must always reorient ourselves to! It is the best possible formulation of our future possibilities. We belong to God alone, so we are being sent into the world with a purpose. The church is being sent into the world with a mission There are plenty of people who say that Mother’s Day was a holiday invented by the greeting card companies. And there’s some truth to it. And I think for a long time that I agreed with the general sentiment. But this year, my first Mother’s Day without my mom, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic and sentimental.

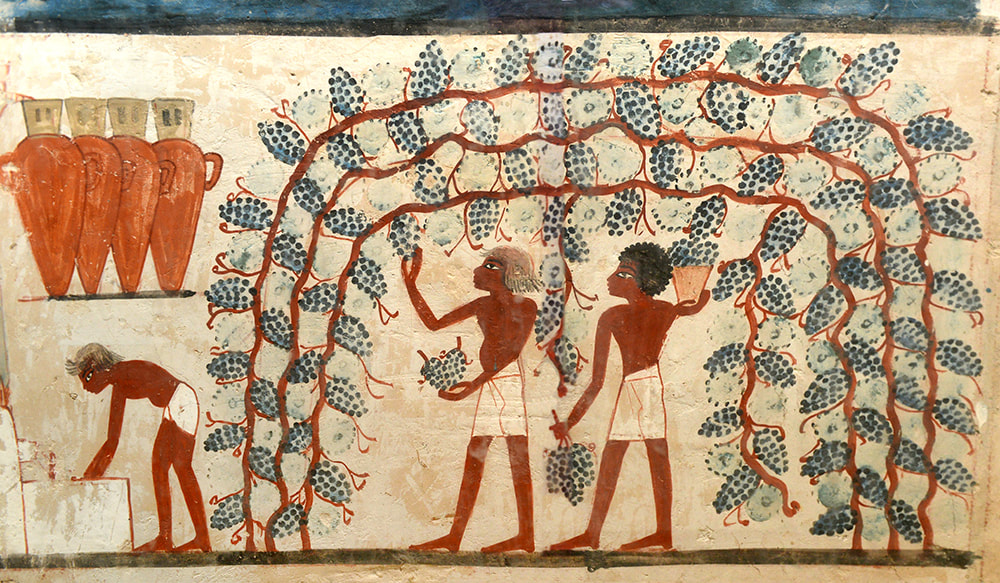

For those of us who were raised by good and loving mothers, like I was, there is a great debt of gratitude to Mom. For those of us lucky enough to know loving mothers, we can say that there’s nothing quite like a mother’s love. So, to all the loving moms out there, you have our gratitude for your love. And on Mother’s Day we should shower you with praise and with flowers and greeting cards. But I also think if we’re truly grateful for the love you’ve given and taught to us, we’ll show our best gratitude by loving others. Now here’s something interesting about being a loving mother and also (like Jesus is talking about in our scripture reading this morning) about being a loving father. The parent who loves you unconditionally, who forgives you endlessly, who accepts you just as you are, and who never gives up on believing in you is also the parent who sets the rules of the house, who enforces those rules, who disciplines and punishes, and who holds high expectations for your own behavior and success in life. As a father myself, the two phrases that most often come out of my mouth are, “I love you,” and “Stop that.” At first glance, certainly from the childhood perspective, this seems to be an incongruous contradiction. I’m grounded again! Why? Because my mom hates me! We don’t like it when Daddy makes us eat our vegetables! Why can’t you just give me the ice cream and chill out, old man? But as we mature and grow, as we mature and grow in love, when we become parents ourselves, we realize that there is no necessary contradiction between unconditional love and great expectations, and we understand that true and healthy love must be both free and boundaried. Our 19-month-old son, Romey, loves to be outside. He’s an explorer and he’s fast and he’s sneaky like the dickens. You can’t turn your back on him for a second. The other day he pointed up into the sky at an airplane, I looked up at it for a second, “Yeah, airplane! Very good, honey!” I turned back around—he was gone. He’s goes like a shot. Bonnie and I have found him in the neighbor’s yard, we’ve found him in the street, we’ve found him halfway down the block. Last weekend we took him to a birthday party in a fenced-in yard. What a difference! It was the most fun the three of us have had outside since he started walking nine months ago. Because there was a fence, we could give him the freedom to be on his own that he desires so much and that he needs. Freedom is important. Boundaries make freedom possible. A strong boundary, in the appropriate place, at the appropriate time is a form of love. “I am giving you these commandments,” said Jesus, “so that you may love one another.” I had a clergy colleague who started at a new church and quickly realized that she had a real problem congregant in leadership at the church—this man was mean, rigid, controlling, and angry. He was always right. He was extremely judgmental. He yelled at other people, belittled them, and said terrible things about them to their faces, in front of other people, and behind their backs. If my colleague, his minister, ever called him on it, he could quote her chapter and verse some rule or commandment from somewhere in the Bible that put him in the right and the opposing party in the wrong. This man was big on the rules, but where was the love? My colleague knew she had to do something. This man was so toxic that he was doing a lot of harm to the community and to the ministry of the church. So, she gathered together the Deacons and the Elders to try to put a plan together to deal with this behavior. Many of those in the room had borne the brunt of this man’s abuse for years. And sitting in the church basement my colleague made an impassioned call for the leadership of the church to stand together, to confront bad behavior, and to set strong boundaries and to impose consequences on those who refused to conduct themselves appropriately. And when she was done, one of the Senior Deacons, looking very embarrassed said, “But we can’t do that! We’re a church! We’re supposed to welcome everybody!” They had the boundless love of Jesus in their hearts! God bless them! But they had low expectations! Some people think the Bible is a book all about what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace”: Grace and forgiveness and love that is free and easy and doesn’t cost you a thing, doesn’t transform you, doesn’t lay claim to you or make demands upon your life once it’s received. “God is love and God loves everybody and that’s all I care to know about it.” It’s a lovely looking playground in your backyard, but there’s no fence, no rules, no supervision, and no expectation that anybody is ever going to grow the heck up. Some people think the Bible is a big book of rules that must be followed to the letter—or else! These folks often fetishize certain of these rules and interpret them in the harshest and most unforgiving manner—like an electric fence that’s keeping all the children out of your yard, rather than safe inside. Of course, neither of these approaches is right. Instead, the Bible, like anything else that is designed to empower you to grow up healthy and strong, is the story of both boundless love and great expectations at the same time. And so there are rules. And you may quibble with some of those rules, in fact, you may well reject some of scripture’s pronouncements, you may say that this or that rule is not compatible with the rule of love we have been given by Jesus. And that’s a mature Christian’s job, right? Jesus says, “I do not call you servants any longer, but I have called you friends.” Jesus’ commandments are not commands of servitude, but the teachings of love. A servant must obey an order, right? But a friend is one who makes a choice. And love must always be chosen, it can’t be forced. Not even God can force us to love her or to love others and have that truly be love. So, yes, we are free to choose. But the Good News of Jesus Christ is not an aimless freedom. It is a freedom which is guided by love. And precisely because it is guided by love, there are rules and expectations. You will be confronted by these rules regularly. Like driving down the road, you’ll see signs reminding you to slow down or sometimes shouting at you “WRONG WAY.” These rules are the signposts of love designed to save you from yourself and to protect those around you when you in your freedom have lost sight of the guiding principle of love. All right, Pastor Jeff, that makes sense. Boundless love, acceptance, and forgiveness require boundaries and they bind us to certain expectations. And then these boundaries and expectations must themselves be understood and interpreted by an ethic of love. You can’t have one without the other. We get it. But what we want to know is—what’s God really like? What kind of a heavenly Parent do we have? Who’re we dealing with here? So, tell us, is God a strict parent or is God a lenient parent? My mom had rules, of course, like every mom does. But as I’ve grieved for my mother these last months and as I’ve processed my relationship to her, the rules (which were so much more prominent and sometimes irksome when I was a child) have faded into the background. From where I stand now, as a son raised, a father raising a son himself, I see the whole story of my relationship to my mother as a story of love. The rules, the fights, the ruptures—these were love’s growing pains. Similarly, I think the answer to our question is that God isn’t best described as strict or as lenient. God is best described as perfectly loving. And what is love? It’s freedom, and it’s boundaries. Freedom and boundaries working on you in tandem until the time comes when you don’t see any difference between them anymore. True love, God’s love, is a self-limiting freedom. So, if you’re the kind of person who rolls their eyes at the ten commandments or gets uncomfortable when Jesus starts talking about judgment, instead of skipping that section or blocking your ears, don’t reject it out of hand. Wrestle with it a bit. See if there is perhaps a call within that story that could push you to a greater love. And if you’re the kind of person who uses the law of the Bible and the promise of judgement as a weapon against others or against yourself, if you take pride in your virtue and feel that righteousness is a competition, or if you bury yourself in shame and guilt for your perceived failings, I beg you to recall the metric of love and to evaluate yourself and those around you by that measure. Sometimes love requires us to put up a fence. And that’s hard work. But more often I think it requires us to tear down the walls. And that is hardest work of all. Nobody said that abiding in love was going to be easy. There is no cheap grace here. No loafing freedom. Love is always a call to action. The Good News should forever be a dynamic tension in our lives—to know that you are boundlessly loved no matter what, and at the very same time to know that that love bestows upon you the burden and the hope of great expectations. Preaching on: 1 John 4:7–13 John 15:1–8 There are few symbols that can be traced as far back in human culture and sacred history as the vine. The grapevine is, after all, an exceptional plant—rugged, growing in soils and climate where other crops won’t take hold, yet producing these great, heavy clusters of fruit—globes of sweet juice held together by the thinnest of skins. And the juice of these ample grapes contains a mystery: it can be transformed into wine, and when we drink that wine, we ourselves are transformed. The vine has long represented tenacity, bounty, transformation, and celebration—it represents life!

In the Book of Genesis what does Noah do after he gets off the ark? He plants a vineyard. In ancient Sumer, at the dawn of civilization, the written symbol for “life” was a grape leaf. Grape vines were sacred to Osiris, the Egyptian god of life and fertility, and they were painted inside of Egyptian tombs as a symbol of resurrection. And we can’t forget Dionysus and Bacchus, the Greek and Roman god of wine, passion, and religious ecstasy. So, when in our reading this morning, Jesus adopts the image of the vine, the true vine, he’s doing it provocatively. He’s doing it with at least some awareness of the symbolism and the importance of the grapevine and its connection to life and to divinity that he’s now laying claim to. But Jesus isn’t just laying claim to the territory of some other grape gods. Jesus does something so much more surprising, so much more outrageous, but we don’t even notice him doing it anymore. Jesus says, “I am the vine, you are the branches.” In all previous history, you could worship the gods of the vine, you could worship grapes as a god, you could drink the sacred wine as a gift from the gods, or you could pour it out in sacrifice to them, but never before in religious history were you informed that you were a part of the vine, never before were you painted into the picture as essential to the symbol’s equation, never before were you so intimately intertwined with divinity. Never before have we been invited to abide in God as God abides in us. That’s the first surprise of this image. Jesus is not a God who’s disconnected from us. Our God is not aloof, not far off somewhere. Do you want to find God? Where should we look? Jesus tells us that we’re as tangled up together, as interconnected with God as a vine and its branches. Now, you tell me, where does the vine end and where does the branch begin? When I was 14-years old, I broke my back because of a bone disease I have that severely weakened one of my vertebrae. I was brought to Boston Children’s Hospital and the doctors there said that my spine was the most severely damaged spine they had ever seen that belonged to someone who wasn’t paralyzed—yet. I remember the light flickering on behind the x-ray of my back and looking inside of myself to that precarious, twisted mess of bone and nerves and feeling so afraid. I remember thinking, “Is that what I am?” It turns out that was a very productive question. The doctors told me they would do their best but that it was a serious operation to put me back together again and there were no guarantees. I needed to be prepared to wake up from the surgery paralyzed from the chest down. I would be under general anesthesia for at least 8–12 hours and I was afraid that I might not ever wake up at all. Anything could happen. Lying on the operating table waiting for the anesthesiologist, mortally afraid of what might happen to me, I made a deal. Now, it might sound a little cliché and unsophisticated, and I wouldn’t always recommend it, and I was young, but it was an important moment for me. I promised that if God would let me live and let me walk and let me heal, that I would dedicate my life to God. I looked deep inside of myself and I promised to become the individual that God most wanted me to become. And when the surgery was over, I was fortunate to have a remarkable recovery. And now that I was healthy and not so terrified anymore, I started wondering about the deal I cut. I knew, after all, even at that age that that’s just not the way things work. Sometimes very good people pray for healing and don’t necessarily get what they’ve prayed for. It could have turned out differently. For many people, in a moment of crisis, it does turn out differently. So, what was the point of that seemingly foolish prayer? Why couldn’t I stop thinking about it? I thought about that promise almost every day for months and months. And slowly I began to realize that the power of that prayer wasn’t about walking or not walking, living or dying, the power of it was that in that moment of ultimate vulnerability I was given a chance to look deep inside of myself and really see who it was that I am—not a tangled mess of bone and nerves and guts—but the very best version of my future possibilities. It was like there was this closed box somewhere deep inside of me holding this calling? opportunity? destiny? and in that moment of vulnerable, mortal prayer I suddenly had a reason to open the box and look inside. And as I continued to heal and continued to grow up, I realized that I was never going to be able to get that box closed again. That was the true power of that prayer—it showed me who I am. It was like I looked down inside of myself and saw that I was not some untethered, withered, broken stick, floating through a meaningless void. I looked down inside of myself and I saw that I was a branch, and I got the briefest glimpse of where the branch begins, of what it is made out of, what it’s a part of. And just the briefest glimpse changed everything. Carl Jung wrote in Memories, Dreams, Reflections, “The decisive question for human beings is: Am I related to something infinite or not? That is the telling question of our lives. Only if we know that the thing which truly matters is the infinite can we avoid fixing our interests upon futilities, and upon all kinds of goals which are not of real importance. Thus we demand that the world grant us recognition for qualities which we regard as personal possessions: our talent or our beauty. The more a person lays stress on false possessions, and the less sensitivity they have for what is essential, the less satisfying is their life. We feel limited because we have limited aims, and the result is envy and jealousy. If we understand and feel that here in this life we already have a link with the infinite, desires and attitudes change. In the final analysis we count for something only because of the essential we embody, and if we do not embody that, life is wasted.” Beloved, part of my calling is to proclaim and to remind and to assure and to reassure you that you, here in this life already, have a link to the infinite. You are a branch. You are a branch. You are a branch. And who can even say where the vine ends and the branch begins? Jesus is our source, God is the ground of our being, and we’re not merely brushing up against them, we’re growing out of them. When we abide in God as God abides in us, we abide in love and we produce the fruits of love by which we will ultimately be judged—by which our lives will be productive or wasted. For our lives to have their fullest meaning, in order to not be distracted by trivialities, we must look down within ourselves to see for ourselves where the branch begins. Where the branch begins is the beginning of everything that matters. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed