|

Preaching on: Luke 2:22–40 The Temple was a place you could put your faith in. Imagine it with me: Approaching Jerusalem with Mary and Joseph and the baby, it’s the Temple that you can see from miles off; it’s the Temple that makes up the entirety of the great city’s skyline. Passing through Jerusalem’s walls, in every quarter of the city, wherever you go, the sky is dominated by the Temple’s immensity. Finally arriving at its base, you see great staircases climbing and twisting up three stories before reaching the height of the lowest courtyards. Cunningly carved out of natural features that had been extensively reinforced and expanded upon over centuries, there are—here at the base—carved stones, some 26 feet in length and weighing up to 400 tons—megaliths so large that today science has lost the arts that could have moved them, let alone place and stack them with such exacting precision.

Climbing up to the heights of the walls or the towers of the Temple, 20 stories above the city streets below, you can see an expanse of open architecture that could hold every cathedral, every mosque, every sacred site you have ever visited in the modern world—all of them together—with room to spare. Spread out over the mount, across a space that could hold 27 football fields, you see dozens of buildings and courtyards, bridges and aqueducts, gateways and marketplaces—each with its sacred and civil purposes, leaving room between for up to one million worshipers. You are looking down upon the largest religious construction in all of human history at the height of its glory. And there at the center of the mount: the Temple itself, the Holy of Holies, the place where God dwells, where the Presence of the Lord IS. In the courtyard just outside it, the blood from sacrifices runs over the hewn stones, and the viscera of lambs, and doves, and bulls sizzles on great beds of red hot coals. The greasy smoke climbs up into the sky to delight the heavenly hosts with its pleasing smells. On the journey home, miles away, if you turn your head back over your shoulder you will still be able to see the thin smudge of dark smoke ever rising, reminding you that the heart of the world is still there, beating, pumping lifeblood, touching heaven in its ineffable way, doing the work that is pleasing to God. The Temple is a place you can put your faith in—ancient, huge, and holy, it connects heaven and earth, humanity and God, the beginning of creation and the end of all times. Its walls contain us and protect us. Its weight anchors us. Its smoke tethers us to the Holy of Holies and lifts us up to Heaven. Babies, on the other hand, are the exact opposite sort of thing from temples. They’re brand new—untested and unproven. They are small, fragile, weak, rather useless and, frankly, ill-formed. Their heads are ridiculously big, their limbs are comically short, it takes years just to get them to use the toilet, and then decades more hard work from extended family, friends, church, teachers, doctors, orthodontists, therapists, coaches, and counselors just to get them their first decent paying job and to actually start being productive members of society. Babies? Babies are—cute. Temples… define us. Babies can’t do anything, they come with no guarantees, no return policy, and are really nothing more than—than a possibility. And you do not know what you are going to get. So, I’m not that surprised that in all the Temple that day, filled with tens of thousands of worshipers and visitors, in all that ancient and mighty place, there were only two old souls—Anna and Simeon—who saw the Baby Jesus and who recognized him for what he was—a messianic possibility, a change in the temple tempo, an unfixed future—and who were willing and able to celebrate this uncertain sort of salvation. Of all the pious pilgrims in the Temple that day only Anna and Simeon held the baby in their arms, sang to him, prophesied about him, and thanked God for getting to glimpse the possibility of the Good News, for seeing with their old, dim eyes this small and rather unlikely beginning. What made Anna and Simeon different from the rest? Perhaps, the Holy Spirit was speaking to the whole of the Temple that day, with a spiritual shout to their souls that said, “Come and see! Come and see the anointed one, God’s Messiah, the Christ, who will reconcile the whole world to God! Who will throw open the doors of the Temple! Who will flip the tables of the money changers! WHO WILL DO THINGS DIFFERENTLY!” And maybe a lot of people did, without consciously realizing it, obey the command and wander through the crowds until they brushed past Mary and Joseph, straining intuitively to get a glimpse of God’s salvation, and seeing—where they had hoped to discover another Temple, another Holy of Holies, another old friend, a Messiah entire who breaths fire and knows my name—just a baby, 40 days old. “Ahhhh,” they thought to themselves in the deep chambers of their pondering hearts, “hmmmm... Not quite what I was hoping for. I think I’ll wait and see. A few miracles maybe, some good sermons like the old high priest gives, and of course a strong arm, natural leader, head of a great army, fond of me. When he marches forth with his army from the Temple mount and reaches down to pull me up on the back of his horse, looking deep into my eyes and touching my soul, then I will follow him... to our certain victory. But for now—too risky, too uncertain. Frankly, it looks like he needs me more than I need him! Ha! So, let me go and make my sacrifice and go home again and if this was meant to be, at some point, he will come and find me.” Anna and Simeon were different. Though they had spent their whole lives in the Temple, though in some symbolic way you could say that they were the Temple, they were willing to put their faith and trust in the disruptive possibility—the mere possibility—of something new—of a baby. And now here we are, poised on the threshold of a new year. Are we like the throngs in the Temple, holding tight to the structures we know, only finding solace in the immensity and certainty of the established, the sure thing? Or are we like Anna and Simeon, with eyes that can spy the eternal in the transient—the divine possibility in a humble beginning? What will we put our faith in in 2024? As you look ahead into the new year, if you’re like me you’re probably dreading some things—the war in Gaza, the war in Ukraine, the presidential election. And when you’re dreading big stories like these or perhaps others or possibilities in your own life, the tendency is to feel that only some big miracle, some grand sign or wonder, some total victory can make the world a better place. But those old souls, Anna and Simeon, tell us that there is another way to find a way through difficult times. Are we ready, like those old souls, to embrace the small, the uncertain, the mere possibilities that lie before us? Possibilities that (just like little baby messiahs) might need us right now more than we need them? Will we have the courage to offer our blessings to God’s possibilities? Or will we go home and continue to wait? God’s work is often found in the unexpected: In imperfect people, in small acts of kindness, in quiet moments of prayer. God's presence is not always where we think we should be looking for it. It’s not always locked away, under guard, in the Holy of Holies. Sometimes it's in the hand that reaches out in compassion, in the word spoken in love, in the heart that gives selflessly. Will I give my very best to the little opportunities to make the world a little better in 2024? Or will I go home and wait for the world to settle down and start being nice again? As people of faith, our call this New Year is to watch for the opportunities that God is offering us to have hope and to make things a little better. It's to believe in God's possibilities, even before they've matured, even before we fully understand them. It's to have faith like Anna and Simeon—who knew deep in their hearts that the possibility in a baby was a greater reason to hope than all certainty in the world. The possibilities for this coming year are as limitless as our willingness to hold them and bless them when they’re still just possibilities.

0 Comments

Welcome to Advent. Advent began last Sunday, of course, but I wasn’t here because of an attack of the COVID upon my house. I’m testing negative now, but still wearing a mask to comply with CDC recommendations.

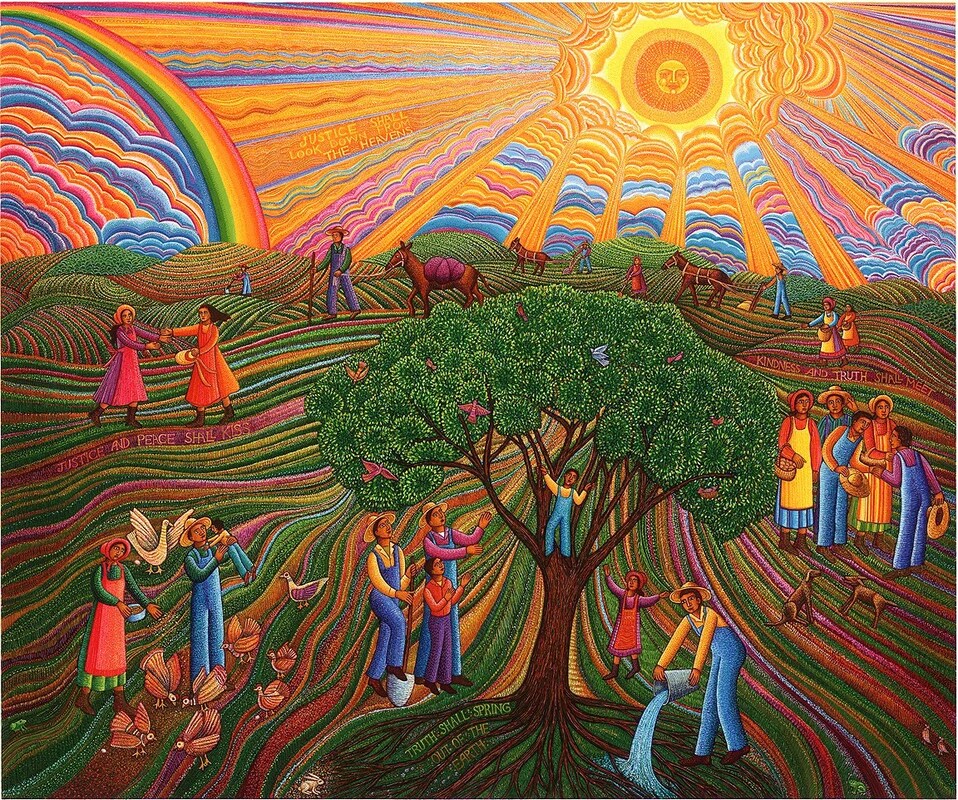

Thank you to everyone who stepped in and stepped up last week to make church happen without me. It’s sort of a wonderful way to begin the new liturgical year—remembering that it takes the gifts of a whole community to worship God every Sunday, not just when I don’t show up. Worship should never be a monologue, it should never be a performance, it should never be consumed. Worship should be as diverse as the community, as robust as the community. Worship requires us. Together, we’re all the resonating chamber of worship. Every one of us is a participant in forming this deep space—the size and the shape of this chamber. And when the Wind of the Spirit blows through us, the music that is produced is produced by all of us. It takes the whole church. I really believe that. So, I account my illness and your readiness to step in and roll with it to be good news for us all on what was the first Sunday of Advent, the first Sunday of this new liturgical year. Advent is my favorite season of the year. Advent is dark. The days are still getting darker. The darkness is getting a little longer each night. The light is still fading from the sky. It’s not Christmas yet. It’s the long, long wait for Christmas. The long, long wait in the dark. It’s not just four Sundays of waiting—Advent stands in for lifetimes of waiting, generations of waiting—for a million, or a billion, or more, long, dark nights of the soul. And at the same time, in Advent, the lights are starting to go up in the night. The tree gets lit in the dark with the tiniest little lights—a twinkling of stars in the darkness. The menorah gets one more candle with each passing night. It’s important to me that we recognize that Christmas doesn’t just happen automatically. Christmas happens because we participate in Advent—all of us, our whole community—we participate. In ancient times, on the night of the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, coming up on the 21st this year, the people would light fires and chant rituals to the sky to ensure that the sun reversed his course, to ensure that he didn’t just diminish forever into the darkness, to ensure that there was a return to the light—that after winter there would be a spring again. As Christians, we recognize that Jesus is the light, the true light that is coming into the world. And it’s tempting to believe that God—being omnipotent, as we’ve been assured he must be, will just take care of everything without us. And yet Jesus came into the world asking us to follow him, to take up our crosses, to participate in the great religious drama of the struggle between day and night, light and shadow, in our world and within ourselves. Worship can’t happen without you. Christmas can’t happen without you. And not everyone will agree with me, but I believe it to be true, that the goodness that God has in mind for this world will not come to pass without our commitment to it, without your participation in God’s plan and Jesus’ way. And I believe that need for you and that participation is best learned in the dark—with the faith and the hope that our participation matters, that it does make a difference. And that’s not easy to feel, is it? Not right now. There are so many reasons to feel depressed and a little hopeless right now. I’m not going to list them all. But I’ll tell you one that’s been particularly on my own mind and heart the last two months—the war between Israel and Hamas: the sickening Hamas terrorist attack of October 7th, the plight of the Israeli and international hostages held in Gaza, the devastating IDF bombings in Gaza, the overwhelming suffering and death of the Palestinians in Gaza, and the disagreement and the moral confusion and the antisemitism and the attacks on Muslims and Palestinians here at home. How can I feel hopeful in the face of such an enduring and divisive and devastating conflict? How can I participate, even in a small way, to help make peace when there is so much virulent and vindictive disagreement about which side to take in this war. People are being persecuted for showing even basic support and compassion to one side or the other. People saying “I stand with Israel” on social media have lost their jobs. People wearing black-and-white Palestinian scarves, keffiyeh, have been shot. Ivy-league presidents have pathetically fumbled basic questions about preventing antisemitism on campus. And at the UN, the US has vetoed the rest of the world’s call for a humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza, because the UN has so far refused to condemn Hamas and the October 7th attacks. So, we’re living in what feels like the worst of all possibilities. Instead of condemning terrorism against Israelis and ending the bombing of Palestinians, we’re suffering a grotesque moral failure of nerve. How do I step into that and actually make a difference? And so we come to the 85th Psalm this morning. The 85th Psalm is a song of restoration. It’s a song sung in a time of darkness, but looking toward the light. It begins by remembering God’s goodness. And it acknowledges that we are living in a time that must be characterized by God’s anger at our failures. And it asks God to intervene again, to show steadfast love, and to return to us again. It is a song that could have been sung on the winter solstice or lighting the candles on a menorah or decorating a tree—God how can we endure this darkness? Return to us again. Return to us again. And then the song turns to hope. The Psalmist turns his eye to what God will surely do for the people. And there are these two wonderful lines of poetry: “Mercy and truth are met together; Righteousness and peace have kissed each other.” When God gets involved with us, and when we act upon God’s involvement with us, it will be possible for truth and mercy to meet one another—it will be possible to condemn terrorism and to call for a humanitarian ceasefire. It’s not one or the other, it’s about finding the way through the dark for the two to meet. Because only if they meet will either of them be possible at all. And true peace will be possible only when it has embraced justice. Peace cannot be made by an occupation or by a wall. Peace requires justice—a redress of the wrongs of the past tempered by the greater hope for the future. And justice will be possible when it has kissed peace. Justice cannot be made by revenge. Justice cannot be made by doing to the other what has been done to you. It can only be achieved by doing to the other what you would have them do to you. Peace must accept that it is too weak to stand on its own. Justice must accept that without mercy and forgiveness it will ravage the world anew. It’s not one or the other, it’s about finding the way through the dark for the two to embrace. Because only if peace and justice kiss one another will either of them be possible at all. Our job as Jesus’ followers is to keep God’s vision clearly in our minds and hearts—mercy and truth, righteousness and peace. In a time of war and division, we are called upon to do what we can to enact that vision without exacerbating the conflict. If we throw up our hands in despair or overwhelm or fear, God’s vision will fail. Where do mercy and truth meet? Where do righteousness and peace kiss? In us! In our hearts and lives, in our communities and in our world. God has sown the seeds for peace and justice in us and the question is, what kind of soil will we be? The Thursday before last, the Montclair Interfaith Clergy Association and the Montclair African-American Clergy Association held “A Sacred Space for Lament and Love During a Time of War” at the UU church in Montclair. We as local clergy got together in October and November and knew that we needed to do something to enact our values here in our community. If we didn’t take a stand of love and support for everyone—of truth and mercy, justice and peace—we knew that greater conflict and even violence might erupt in our own community. And we knew the only way we could achieve such a space—such a resonating chamber—was by including the participation of everybody. And so local rabbis spoke, and a local imam. A Palestinian-American woman spoke. And an Israeli-American woman spoke. Each spoke their truth in turn. And after each person spoke their truth, all of us in attendance—about 100 diverse community members—said together to that person, “We hear you, and we love you.” It was not an end to war or to conflict. It was not the dawning on that great morning we all hope and long for. But it was a beginning. And it was profound. It was an utterance of truth and mercy, of righteousness and peace, spoken from the depths of the darkness, calling the light back into the world. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed