|

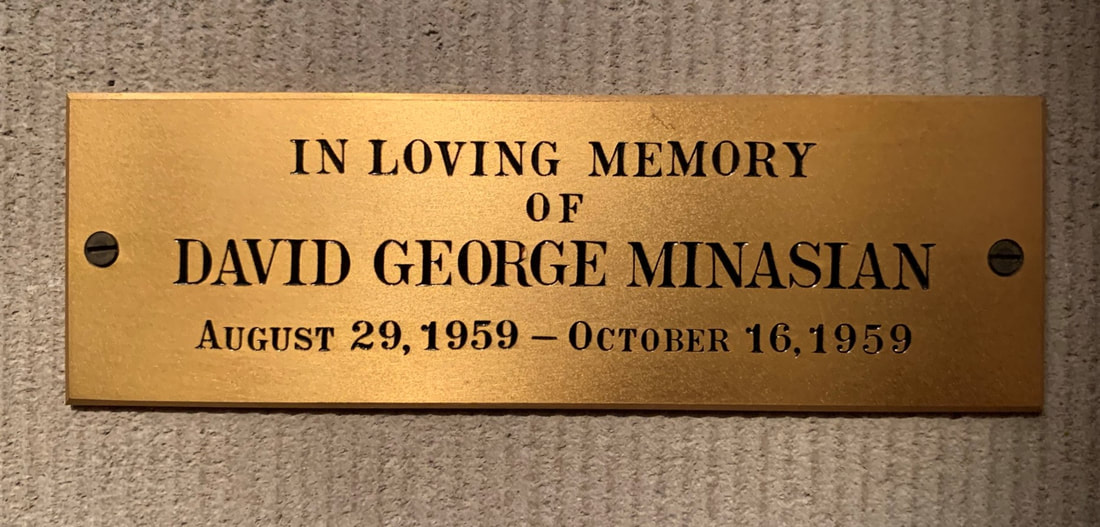

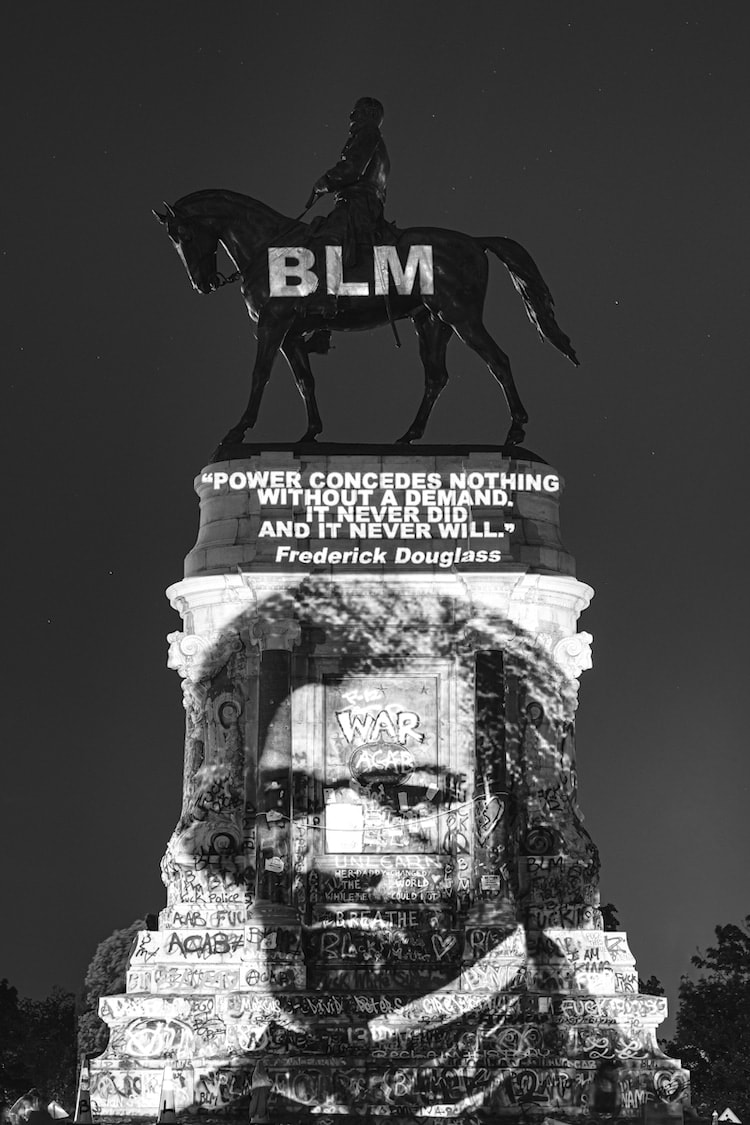

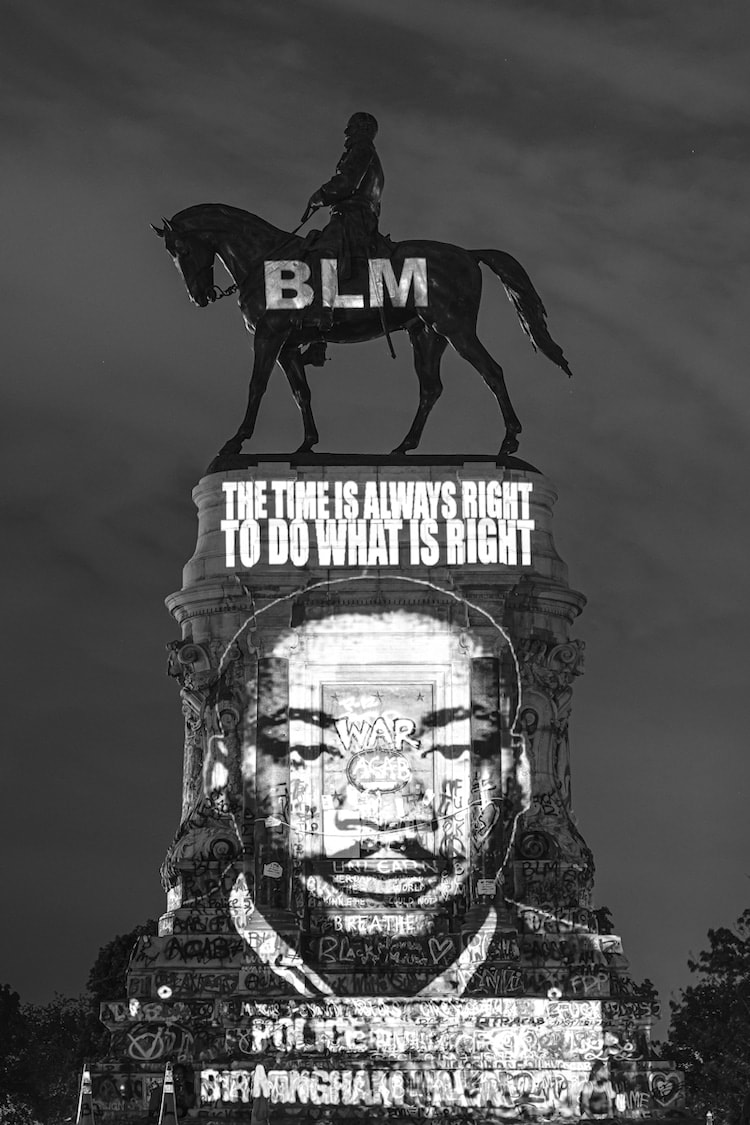

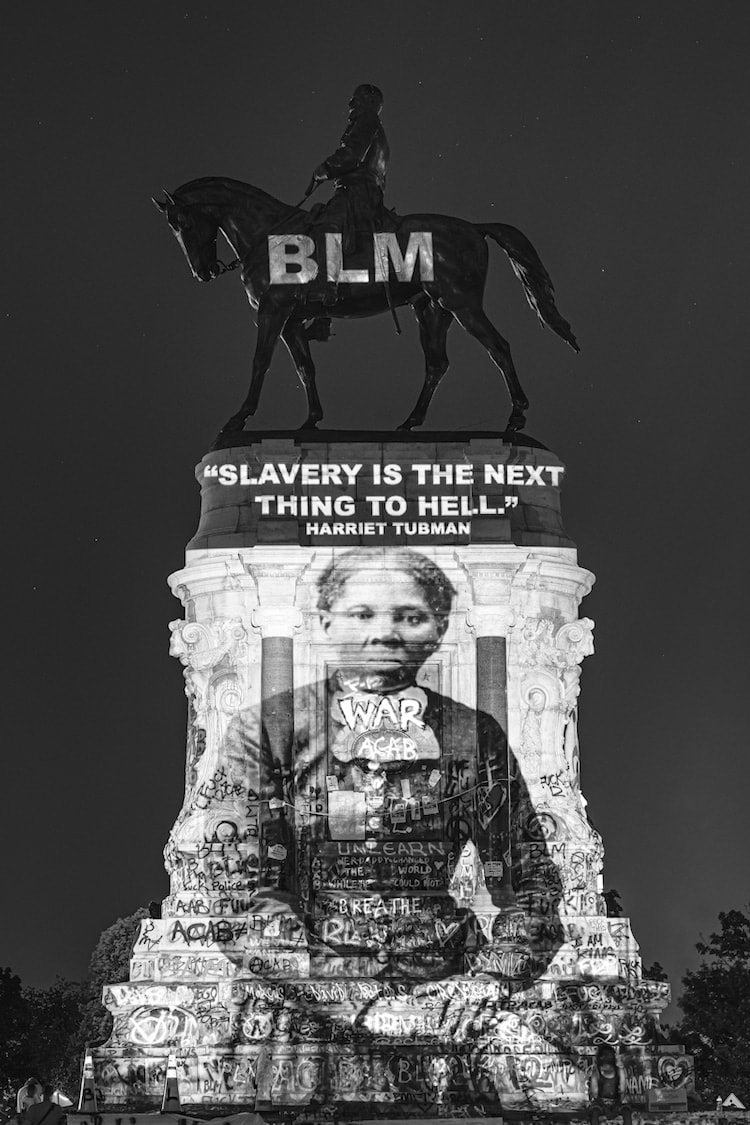

Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.” So God created humankind in God’s image, in the image of God, God created them; male and female God created them. —Genesis 1:26–27 (NRSV, alt.) Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter and James and John, and led them up a high mountain apart, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his clothes became dazzling white, such as no one on earth could bleach them. And there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who were talking with Jesus. Then Peter said to Jesus, “Rabbi, it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” He did not know what to say, for they were terrified. Then a cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud there came a voice, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” Suddenly when they looked around, they saw no one with them any more, but only Jesus. As they were coming down the mountain, he ordered them to tell no one about what they had seen, until after the Child of Humanity had risen from the dead. —Mark 9:2–9 (NRSV, alt.) In my sermon this morning I’m going to be talking about racism and transfiguration. And I’m indebted in my thinking here to a former Minister of Racial Justice for the United Church of Christ, Rev. Elizabeth Leung. I couldn’t have gotten to this place without her work. So, thank you, Rev. Leung for your ministry. OK, I’m gonna start you off with a quick Sunday School lesson this morning, just to lay the foundation down for you. Then we’re going to climb a mountain to see what we can see and to see who we might be. Then I’m going to tell you why I’m over here on this side of the chancel at the lectern instead of standing over there at the pulpit like I usually do—I know you’re all dying to know why: stay tuned to find out! OK, Sunday school first! Gather ‘round little ones: Genesis tells us that we human beings have all been created in the Image of God. What does that mean exactly—created in the Image of God? Does that mean that God has thumbs, just like me? A bellybutton too? A spleen, perhaps? Aside from the unfortunate fact that the patriarchy has still got many of us pretty convinced that God is a man, we’ve mostly understood for a good long time that God isn’t like us like that—in physical form. It’s other things—language, morality, consciousness, love, creativity—these are the ways we’re created in the Image of God. God doesn’t look like us! But, still, somehow, we still look like God. There is still something sacred about the physical human image in all of its created diversity—because God created humanity to be physical and to be diverse. And I believe that our physical diversity of sex, gender, sexual orientation, race, body shapes, sizes, and abilities is a part of our creation, a part of our humanity, and therefore a part of our reflection of the Image of God. So, it’s not just morality and creativity and language that make us reflections of God’s Image. It’s also our diversity. And diversity joined together through the bonds of loving relationships is called community. Human beings were created to be in beloved community together. That’s part of what it means to be human. That’s part of what it means to be God. After all, doesn’t God say, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness”? When your species reflects God, you don’t look like just one thing because God contains multitudes. God talks to herself. God is everything. So here’s the Sunday School lesson for Racial Justice Sunday: Because we are created in God’s image and because it is in our very diversity that humanity most fully reflects God’s Image, racism is not only a sinful human system of devaluing, oppressing, and exploiting people based on the color of their skin, racism is also a disfigurement or a disfiguration of the Image of God inherent in Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color. Someone once asked Jesus, “What is the greatest commandment?” Jesus said love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind. And a second is like it: Love your neighbor as you love yourself. And a second is like it. These are not two arbitrary and unrelated commandments. They are deeply connected because if you hate your neighbor, if you oppress your neighbor, if you devalue your neighbor, you are desecrating and disfiguring the very Image of God that you claim to love. This is all stuff we should have learned in Sunday School: God doesn’t have thumbs (and isn’t an old white man with a beard), but we still look like God (all of us) because we human beings are thinking, loving, and beautifully diverse. Racism is an evil that infects the way we think, infects the way we love, and infects the way we live together. It’s a sin against God and a sin against our neighbors. It is a systemic social disease in effect, but it is a systemic spiritual disease in origin: It is a disfigurement of that which is most human—God’s Image. Racism is a disfigurement of that which is most human—God’s Image. That make sense? OK, Sunday School lesson is over. Now, we’re going to go out for a little Sunday hike. We’re going to hike up a mountain with Jesus, and Peter, James, and John. We climb and we climb and we climb, and when we get to the top, we look out over the world and Jesus is transfigured: He’s shining with light, his clothes are brighter than any white fabric we’ve ever seen, he’s talking with the spirits of Moses and Elijah, and we hear the voice of God. Jesus’ human form which had always reflected God’s Image is now radiating God’s Image. Jesus’ body has become like the burning bush—God is literally shining and speaking through him. Instead of a disfiguration of God’s image, Jesus’ shows us what transfiguration looks like—that transfiguration is possible. We learned in Sunday School, of course, that Jesus is fully human and fully God at the same time. The mistake we make when we climb the mountain is that we assume that Jesus’ transfiguration is a part of him being fully God. But I think the transfiguration is about being fully human—as God intended us to be. When the burning bush appeared to Moses, was that particular bush chosen because it was fully God? No, it was simply fully bush—transfigured by the energy of God, burning but not consumed. We live in a racist society. All of us in this society are witnessing a disfiguration of the Image of God all around us that dehumanizes all of us and that limits our ability to participate in God’s fire, God’s light, God’s energy. The Apostle Peter warns his readers that participation in sinful ways can block us from “becom[ing] participants of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:3–4).To correct this disfiguration of God's image within us we need a culture-wide Transfiguration towards what Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called the Beloved Community—a diverse, antiracist society ruled by justice and love. We, the Church, are the Body of Christ. And if Christ’s body was transfigured on the mountaintop, then this Body of Christ can be transfigured too. Like Paul wrote in 2 Corinthians, “All of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transfigured into the same image. ”God gave us God’s own image. We have disfigured that image. And through Jesus, we can transfigure it too. The more we become fully, justly, lovingly, diversely human, the closer we come to the one who made us so. OK, very good, would you please tell us now why you’re standing over there. It’s driving me crazy. All right! I’m at the lectern this morning because I want us to imagine what the first steps of transfiguration could look like in our church. And, so, I wanted to preach with this piece of artwork behind me. I’ll let you take a closer look—buckle up! Just take a look. What do you see? Who do you see? Who do you not see? I see Jesus sitting on a little hill of sorts. And he almost looks like the transfigured Jesus. His clothes are perfectly white. And he’s surrounded by light. This isn’t the transfiguration though, it’s a representation of Jesus allowing the little children to come to him after the disciples tried to chase them off. What you can’t see on screen is that there’s a plaque underneath this painting that says, “In loving memory of David George Minasian, August 29, 1959–October 16, 1959.” The Minasian family was a very prominent family in our congregation and community. For 110 years we’ve been giving out the annual Minasian Bible Award to an outstanding Christian educator in our congregation. And the stained-glass window “Righteousness, Truth, & Beauty” was donated by the Minasian family. And one of the Minasians was a mayor of Glen Ridge in the 1940s. Little David Minasian was less than two months old when he died in 1959. I can’t imagine the pain of his mother and father, his brothers and sisters, his grandparents as they sat in these pews in their grief. I hope I never know pain like that. And I am so glad that they had a church that let them paint their grief and their hope and their love on the wall of the sanctuary. Amen to that. All that being said, we must also observe the painfully obvious: that everyone in this picture is white. It is a reflection no doubt of its time and culture, and we must remember it was the time and culture of segregation and Jim Crow in this country. We see that Jesus is depicted as a white person of European descent. Of course, we all know that Jesus was not white. Jesus had no European ancestry. He was a brown-skinned, Middle-Eastern Jew. Now cultures all across the world have tended to depict Jesus in their own image. But in our culture, which has so often preferred and uplifted the image and form of white people while denigrating and disrespecting the images and forms of people of color, is it justifiable to continue to entertain the comfortable fantasy of white people that Jesus was white? There are 16 children in the painting, they are all white—every last one. And I mean really white. These kids have not been to the beach lately. And I have no doubt that in 1959 that was an accurate reflection of the demographics of this congregation. But God be praised that is no longer the case. We are Black, we are South Asian and East Asian, we are Middle Eastern and Cuban and Brazilian and mixed race and bi-racial and more. If you were a child of color looking at this image at the front of your church, what would it say to you? I think it would say to me: You have no place in God’s Image. That is a racist message that cannot be ignored or allowed to stand unchallenged in this congregation. It must be transfigured. How do we do that? I don’t know! We’re going to need to think about that together, and I hope we do because there is an opportunity here for us—an opportunity to see God more clearly. Now, you all know that we’re in the midst of a culture war over one kind of “art” in particular—confederate statues. There are a lot of people who want them taken down because of the pain of having to see an individual who fought for the cause of slavery glorified in public art. And in some places, the powers that be are taking them down. And in others, the powers that be are leaving them up. And in some places the people are organizing to tear them down without sanction or permission as a form of protest. I’ve never been a big fan of the Confederates, personally. I never routed for that team. And I agree that there is no place for confederate statuary in our public commons. I don’t mourn them being taken down or torn down at all. But then in Richmond, VA there is a 12-ton, 60-foot-tall statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The crowd who tore down the other confederate statues in town couldn’t budge this one. And its ultimate fate is tied up in appeal in the courts. And then something incredible happened. After the murder of George Floyd last year, this statue of Lee was transfigured by an artist named Dustin Klein. So much so that now a statue of the quintessential confederate general has become an emblem of the Black Lives Matter movement and the area around the statue has become a gathering space for the movement and the wider community. Let me show you a few pictures of this transfiguration: With our picture of white Jesus welcoming the white children we could decide to take it down from the wall. We could decide to cover it up somehow. And we could decide to transfigure it in some good way. But what we can’t do is we can’t ignore it or dismiss it—that would be a missed opportunity and a disfiguration of God’s Image.

And obviously we’re not just talking about this because we only just need to transfigure one painting. We’re talking about this as a concrete example of how we can begin to transfigure ourselves, our church, and our wider community. We want to see God more clearly. We want to be truly diverse. We want to participate in God’s divine energy. We want to be an antiracist congregation; we want to be a part of the great work of our time—of ending racism and solving these deep structural problems with love and justice. So, let’s end with Jesus’ own prayer for us. At the close of the last supper Jesus prayed to God, “The glory that you have given me I have given them, so that they may be one, as we are one, I in them and you in me, that they may become completely one.”

0 Comments

|

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed