|

The gospels don’t name her. But we know from other historical accounts that Herodias’ daughter was named Salome. And history has not been particularly kind to Salome. Is that fair?

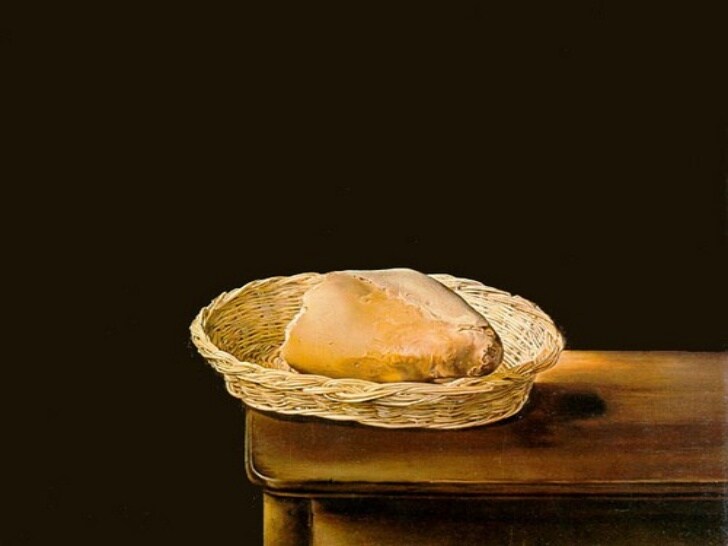

Christian theologians have interpreted her as a lewd temptress (all that dancing): Conniving, cold, cruel, and feminine. Classic Western art used her as an excuse to eroticize the body of an often young girl dressed in silks, her face flushed with her exotic dancing. And Salome was frequently painted holding the platter with John the Baptist’s head on it—never Herod or Herodias—but young Salome, looking off into the distance—aloof or silly. More modern Western art has continued the trend: Salome the child has been transformed into the archetypal femme fatale. Not merely lascivious, but a sadist and a psychopath—sensually aroused by severed heads. And so Salome has shouldered the blame—as women and girls so often do. Even though Herod imprisoned John, and even though Herod made a ridiculous promise to give Salome anything she asks for—as if he can assume it’s going to be a nice request, but then it’s not nice, but he has to do it anyway because of his manly honor— But it’s not his fault because he was deceived…by a woman. And even though it was Herodias’ grudge against John, and even though it was Herodias’ request that John lose his head, and even though Salome is a kid stuck in the middle of the great powers of her day—king father, queen mother, imperial guests, divine prophet, it is Salome (hoisting the platter in her skimpy dress, staring vacantly toward the horizon) who shoulders the blame for John’s beheading. Is that fair? Can you imagine? You’re thirteen. You’ve just nailed your dance recital. Your number was a present for your stepdad, Herod, who also happens to be the king, who also happens to be your uncle—it’s weird! Anyway, he loves it. I mean he really loves it, and all the other men seem to love it too—it’s weird! Anyway, this might finally get your mom off your back because she’s been so stressed out about this stupid party. And then Herod says, “You can have whatever you want!” And you stop yourself just before you blurt out, “PONY!” because you know your mom’s been having a tough time. You decide to do something nice and ask her what you should get—as a gift to her now that you’ve given his Royal Highness Uncle Stepdad his gift. “My sweet girl,” Mom whispers. “Always thinking of others. Be a dear and ask for the head of John the Baptist.” Is that fair? What would you have felt in that moment? What would you have thought as you walked in your leotard and tights from Herodias to Herod to execute mom’s request? I can imagine myself thinking something like the opening lines of our poem this morning: “There are days I think beauty has been exhausted.” Have you ever felt like that? Can you imagine feeling like it’s not just that the world around you that’s ugly, but that your participation in the world—your dance, your passion, your gift is suddenly revealed to be a part of the world’s brutality. And the ringing of the applause in your ears turns from universal praise for your art to the rally of a partisan and pitiless assault on some poor prophet in prison. And what will you do? What are you going to do? Would you have defied your mother if you were Salome when you were maybe thirteen-years old? I don’t know. Defiance of one’s parents takes either the absolute certainty that they’re never going to stop loving you or the ability to leave them behind and to make it on your own without their support. And I don’t imagine that Salome had either of those luxuries. So, what would you have done? I can imagine myself walking slowly and unsteadily back to the throne, unsure of myself, just torn to pieces. I’d be frantically running through my narrow options, desperately seeking for the margin of error that will let me slip free without destroying myself. But that’s not what Salome does. I can imagine myself walking up to the throne with a lump in my throat, barely able to speak. I’d whisper to the crowd that Mother wants John the Baptist’s head. And in the commotion that follows, I’d slip out the side door. And no one would ever associate me with the death of some hairy old prophet down in the dungeons. No one would blame me. All they would remember was my dancing—my beautiful dancing. But that’s not what Salome does. I can imagine myself defeated and empty—just getting it over with. I would walk back at an unremarkable speed, with my head held at an unremarkable angle, and repeat at an unremarkable volume the words that were given to me, “Bring me the head of John the Baptist.” But that, according to Mark, is not what Salome does! Instead, Salome rushes back to the throne like a ballerina jeté-ing across stage and shouts—with a twist, “I want you to bring me at once the head of John the Baptist—on a platter!” A head on a platter is a bit of a cliché nowadays. But from what we can tell, when Salome came up with this it was original, and inventive, and uniquely—what? Gruesome? Beautiful? At first blush, it’s hard to call a severed head on a platter beautiful. But then we have to wonder why it is that there are so many paintings and sculptures of John’s head on Salome’s platter filling our museums and our churches. You have to wonder: If John was just a head, by itself, rolled off into some dark corner somewhere, without a platter, would his naked, neglected noggin have inspired so much great art? It’s definitely not the gore that’s beautiful. But that platter is a statement, isn’t it? It’s the juxtaposition of the head and the plate. The platter became the vehicle of John’s message and story in death. And it’s surprising, and gruesome, and strangely beautiful. So, why’d she do it? Why’d she do it? Was it merely for this strange aesthetic effect? Why does an artist bring a severed head on a platter into her stepdad uncle’s birthday dinner? Salome is a performance artist! It’s not that she’s overly fond of severed heads. She’s thinking of her audience. Her mother has asked her to present her with a gift. And while Salome doesn’t see a path to directly defying her mother’s request, she decides that instead of presenting her mother with John’s head, she’ll confront the whole feasting assembly of the powerful with the brutality and the extravagance of their rule (which was the same project that John the Baptist had dedicated his life to). She does it by placing John’s head on a serving platter and having it brought into the banquet for everybody to feast their eyes upon. And now we’re meditating on a deeper level of beauty. Because Salome, who I think at least in part is an artist and a fighter—certainly “artist” and “fighter” are better descriptors for her than some of the words that history has assigned to her. So, Salome the artist, the fighter, the angry kid is asking us what purpose beauty serves. Are the beautiful things in our lives meant to distract us from the ugliness in our world? Or does the real beauty come when we find creative, subversive ways to call out the world’s ugliness? In our poem, Meditation on Beauty, J. Estanislao Lopez struggles with this same question. Can the beauty of our trash at the bottom of the sea being recycled into coral reefs redeem us from the brutality of our environmental onslaught. Or is it all just a human amusement as the oceans warm and rise? The poem succeeds, in part, because its beauty is not just a surface beauty—it confronts us with those devastating warming waters, with the turtle who doesn’t see the surface beauty we see, who only lives or dies by what we do or do not accomplish. Lopez’s poem is like Salome’s platter in that way: beautiful and fierce. I’d like to make the world more beautiful. How ‘bout you? You do? Well, what do you want to do? What are we willing to do? We won’t be chopping any heads. But we may have to take account of all the heads that have already been severed, all the necks currently lined up on the block. There are so many! And they have so many fierce stories to tell. And there are so many beautiful platters! But there are so few that we want to get blood on. So, what platters, beloved, do we have to offer? What beautiful thing do we have that we’d be willing to sink to the bottom of the ocean with a prayer? What ugliness, what brutality or sin, what trouble can we crash into like dancers transforming the stage—transforming this weary world, with a twist?

0 Comments

Preaching on: John 6:51–58 I love zombies. And if a zombie apocalypse of any kind actually does happen, you should know that I’m the guy you want to stick by when the dead rise from their graves to end civilization as we know it. I’m gonna be one of the ones who makes it. I’ve read the comic books, I’ve watched the movies and the TV shows, I’ve played the video games, I’ve done all the research. But more than all that I believe I have discovered the secret zombie antidote that no one else is talking about. It’s like the Hydroxychloroquine of the zombie plague, only I think it might actually work.

Now, sure, there are a lot of more likely contenders than zombies for the cause of the end of the world: nuclear war, climate change, asteroid strike, deadly pandemic. But for whatever reason, if I had to choose, I’d choose zombies—hands down. There’s just something about them that’s captured the dark side of my imagination. And I’m not alone in that. We have a zombie-saturated pop culture. In the 100 years since the first zombie tales were imported from Haiti, the zombie has risen to become the ubiquitous titan of both the horror genre and of our fantasies of the apocalypse. Why are we so fascinated by zombies? Well, in the zombie masses—so mindless, so restless, so violent, so endlessly, ravenously hungry—we recognize something of ourselves, over and over again. There’s a moment in most of the great zombie stories where the audience recognizes that zombies aren’t all that different from us, or there’s a moment where a character realizes that the small pockets of humanity that have escaped being eaten by the zombie horde do not really behave all that much better than the monsters do themselves. The zombies don’t just scare us, they resemble us at our worst, and that’s really frightening. But I think there’s something even deeper—something deeper that we’re subconsciously contemplating when our imagination is drawn into a zombie story. Which, obviously, brings me to our scripture reading for this morning. At the heart of the Christian worldview is this wacky idea—eating the flesh and drinking the blood of Jesus. It’s a little disturbing. During the second century when Christians were being persecuted by the Roman Empire, one of the charges that was leveled against us was that we were cannibals. It wasn’t true, but a reading like today’s reading helps you to understand a little bit where the confusion might have arisen from. I mean, eat your flesh and drink your blood? Gross, Jesus. Also, read the room. People are not taking this well. As the story continues, many of Jesus’ followers, unable to understand the acceptability of such a strange teaching, stop following Jesus. It’s a mystery of faith, I guess. And it’s hard to say anything about a mystery, right? That’s the thing about mysteries—they’re beyond us. But sometimes it can be helpful to look at the shadow that a mystery casts. When we see the shape of that shadow, we learn something more about whatever is casting that shadow. And I think the shadow manifestation of this mystery in our time is something we’re all too familiar with—ZOMBIES. Zombies destroy the world. Christ, the logos, created the world. Zombies rise from their graves, killing the world and making a mockery of life with their gross, decayed bodies and their peculiar appetites. Jesus promises to raise us from the grave on the last day, giving us new life on a renewed earth. In zombie stories, hell overflows, and the damned walk the earth where all they want to do is to eat your flesh and drink your blood. And if they bite you, you become an undead zombie yourself. In the gospel, God chooses to come from heaven to walk among us in the form of Jesus asking us to eat his flesh and drink his blood, and if we do, then we have eternal life—the biggest kind of life, which is the antithesis of turning into a zombie. Zombies represent the very worst of our carnal natures. They are decaying. They are mindless. They run together in mobs. They are relentless. They don’t feel anything. They devour everything. They’re never full. They’re contagious. They are the rotten embodiment of the very worst aspects of all flesh. A zombie appears to be able to “live” it’s undead existence forever, but zombies are the exact opposite of eternal life—of the biggest kind of life. They are the horrific inversion of the idea of a loving God offering true food and true drink to us. If you want to understand the mystery of the flesh and the blood, don’t think of cannibalism, maybe don’t even think of communion, think of the opposite of the zombie apocalypse. I tend to agree with Martin Luther who didn’t believe that this passage was about communion (either literally or symbolically) at all. That’s one way of sort of dismissing it (Ah, he’s just talking about communion), but we can do better than explaining it away. If it was that simple, why did Jesus let all of those disciples walk away from him not understanding? I think that Jesus goes so far as to command us to eat his flesh and drink his blood because in Jesus’ incarnation the full goodness of the human body, the full goodness of the world, the full goodness of creation, and of flesh and blood and resurrection itself is realized. If zombies represent the very worst of our carnal natures, Jesus wants us to know that there is also a very best. That’s something we don’t always realize. Sometimes, we think it's all gradations of bad sloping steeply down to the zombie apocalypse. But it’s not. God made this world and made it good. God made the human form and made it good. God formed your body in your mother’s womb. And God even took on the form of a human body for herself through Jesus. A religion that believes that God came to us in the flesh is a religion of believers who are, in some way, immune to becoming zombies. Flesh is too good, too holy, to go so wrong. When Jesus offers us his flesh and blood, he’s reveling in the goodness of all creation for us and in the goodness of our bodies for us and in the goodness of intimacy between us. We carry so much shame around bodies. We’re so judgmental about the bodies of others and our own bodies too. How often do we label as GROSS that which God simply called good! So, Jesus reminds us: To the horror of grossed-out Christians through the centuries, Jesus comes to us as with the goodness of a living, breathing, laughing, crying, chewing, swallowing, digesting, walking, running, jumping, stumbling, gendered, sexual, sneezing, sensuous, fleshy, human body. Believe that—believe it with the shocking passion of eating it and abiding with it as closely as flesh in flesh—and you might just be able to believe that the body God gave to you is holy as well. And it doesn’t have to be gross. Cannibalism is gross, but that’s not what this is. As long as we can trust that this is really not cannibalism, we can let ourselves explore this divine cuisine. Instead of being gross, could it be intimately delightful? The poet Li-young Lee gets at this, I think, with his poem From Blossoms: From blossoms comes this brown paper bag of peaches we bought from the boy at the bend in the road where we turned toward signs painted Peaches. From laden boughs, from hands, from sweet fellowship in the bins, comes nectar at the roadside, succulent peaches we devour, dusty skin and all, comes the familiar dust of summer, dust we eat. O, to take what we love inside, to carry within us an orchard, to eat not only the skin, but the shade, not only the sugar, but the days, to hold the fruit in our hands, adore it, then bite into the round jubilance of peach. There are days we live as if death were nowhere in the background; from joy to joy to joy, from wing to wing, from blossom to blossom to impossible blossom, to sweet impossible blossom. “O to take what we love inside!” Eating is the one thing that all people must do to stay alive and the one thing we all do to take what we love inside of us. So, Jesus offers himself up as food—first as spiritual food, but then he makes sure to remind us that he is a spiritual food wrapped in real good flesh, full of life’s blood. He is alive, truly alive, incarnate and embodied—and, praise God, so are we! “from blossom to blossom to impossible blossom to sweet impossible blossom.” Eating Jesus is not like sipping on air. It’s like sitting down to dinner in a steak house. There will be meat to chew on, jus to savor—life is a delight and God made it good: “to hold the fruit in our hands, adore it, then bite into the round jubilance of peach.” Zombies drain all the jus from the world. They bite delight. A world that can produce such monsters can’t be trusted or loved. But Jesus offers us the opposite vision—not a dead world devouring all flesh, but the living God feeding all the world, getting close to all the world, with the goodness of body and blood. A closeness so overwhelming, so intimate, so good, so delightful that we want to sing to God, in the words of John Denver: You fill up my senses Like a night in a forest Like the mountains in springtime Like a walk in the rain Like a storm in the desert Like a sleepy blue ocean You fill up my senses Come fill me again When Jesus says, “Very truly, I tell you, whoever believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life,” I think about my mom’s death—about her dying actually. When I arrived at the house Mom was conscious, but not really responsive. Sometimes her eyes opened, but you could tell that she wasn’t seeing us there in the room anymore. Her gaze was elsewhere. People who are dying, in those last few hours, usually turn their eyes away from all of us, so that they can turn them towards God. There’s a longing at the very end for the transformation of death, which is also a transformation in God.

I was there in the room with my father, my sister and her fiancé. There was so much grief and sadness in the room, but also something more that we were experiencing. There was an intimacy and (there’s no other word for it) an aliveness in the room. It was a deathbed, but it was more. We could all feel it. Mom’s eyes were on God, and we couldn’t take our eyes off Mom. When Mom finally stopped breathing and slipped away, I did something that really surprised me. After about 15 minutes or so, I took a picture of my mom with my phone. It felt to the everyday part of my brain like a really weird thing to do. “Why would you want to remember her like this?” That’s what my brain was asking me—the part of my brain that couldn’t fully believe that faith, hope, and love are greater than death, the part that wanted to run away from the terrifying aliveness that I was feeling in that room. But the greater part of me knew that we had all come fully alive in that room together—Mom included. In that sacred mix of sadness and beauty, pain and truth, we experienced not only death, but also the biggest kind of life. And so I wanted to take a picture of Mom like that. I want to remember that. Until you’ve experienced it, a deathbed feels like an awfully strange place to come fully alive. We think of coming alive as skydiving, new car smell, the second cup of coffee in the morning. And, yeah, all that exhilarating stuff is a wonderful part of coming alive. But if it’s possible to come alive at a deathbed, if we can even come alive while dying, maybe we underestimate the wideness of Jesus’ eternal life—its breadth and its persistence. Eternal life is not narrow, it’s not timid. We come fully alive in life’s mountaintop moments, of course, but do we need to be any less alive trudging through the valley of the shadow of death? Eternal life is a long life, obviously. But is that all it is? My mom got her threescore years and ten—not a short life, not a long life. But time is neutral. It’s not the length of a life that matters, it’s what fills that life, it’s how often in life we manage to come fully alive in the moment, whatever that moment may hold. Jesus says, “Very truly, I tell you, whoever believes has eternal life.” He doesn’t say “will have, up in heaven, by and by.” He doesn’t say, “when they’re raised from the dead on the last day, it’ll only happen then.” He says HAS eternal life. If you hold the bread of life, then you possess eternal life here and now, on this earth, in this body, eternal life has arrived to us. Every now and again there’s a moment or two in this life, maybe even a transcendent moment or two when you feel God actively moving through you like a fire, and you come alive. But for most of us, those moments are few and far between. And we’re left to wonder in the long, cool stretches between them just what it is that really makes us come to life. What makes me come alive? None of us is all-the-way, all-the-time perfectly alive. We’re only truly alive part of the time, and the rest of the time we just sort of exist. God calls us from existence to life! But sometimes we get stuck, held back. First problem: We don’t really believe in eternal life. Maybe we hope for heaven after we die, but we don’t really believe in the kind of eternal life that says this existence, this world, could be better and more meaningful than we expect. And we don’t expect much. We don’t think things can change, other than anticipating that things will probably only get worse. We don’t have much faith in people or much fondness for their foibles. And we certainly don’t believe that God has the power to turn this world upside down. When I was in Somerville, MA we had a scrappy little church. If you could have seen that little old building. Oh, boy. Built by Scotch Calvinists on the cheap. The entire footprint of the building would fit inside this sanctuary. Even still, when they built it, they didn’t pour the foundation all the way out to the walls, so the walls of the church sat on dirt. Which may have saved a little money, I guess, but after a century it wasn’t much good for our walls. Whenever we’d sing “The Church’s One Foundation” in worship the Building & Grounds Committee would sing “The church has no foundation…” to help raise awareness of our unique plight. It was a stucco building. Stucco in Boston? We wondered if had some special meaning. Maybe one of the church’s founders had made a mission to the Southwest or something. We looked into it, and it turned out that stucco was just the cheapest way to side a building in 1913. The city of Somerville used to have four congregational churches. We were the last one, and no one thought we were going to make it. The denomination had written the church off. There was no budget, no savings, no endowment. At one time they got down to about 15 members. But today it’s a thriving, growing church. People would come from all over the country and say, “How? How did you do it?” My colleague, Rev. Molly Baskette, published two books about it, trying to answer their questions. Why two? Well, we did a lot! There were a lot of technical answers. We changed coffee hour, we flew the rainbow flag, we became a testimony church, and on and on! And all those things were a part of it, but were they the fundamental answer to how or why the Holy Spirit showed up and set a fire in the heart of the church? Looking back on it, in retrospect, I feel sure about one thing that made a true difference. When the church got down to 15 people, those 15 people believed that a church, of all places, is a place where you must expect transformation. They expected and they desired to be not larger, not richer, not prettier, not more respected but to be a church where lives are changed—where people come to experience the biggest kind of life, where they meet God, get sober, get married, get over their divorce, come out of the closet, have kids, change careers, change the way they spend their money, change who they think of as their neighbor, change who they are to the world. Church, of all places, is a place where we expect the biggest kind of life to change all of our lives for the better. This to me is really Christianity 101. The reason we don’t expect much is because we don’t believe anymore the truth that we learned in Sunday School, “I am a child of God.” In his sermons, Howard Thurman would go back again and again to the Parable of the Prodigal Son. You remember this story: At some point the youngest son is old enough to leave home so he asks his father for an early inheritance, leaves his family behind like they’re dead, and squanders his money on loose living—nasty stuff! You know what he was up to—disrespecting himself, disrespecting others. Things get bad (as they do), the money’s all gone, he’s got to get himself a job tending pigs, and he lays down in the mud with them and eats their scraps to feed himself. And one day, covered up to his chin in pig squalor, something he was taught as a child—not even taught—something he had always known but that he had forgotten comes crashing back into his brain. He sits up the pigsty and cries out, “Am I not my father’s son?” And just that realization—that he is a beloved child of God—is the beginning of the transformation of his life. Beloved, remember, you’re a child of God. And a child of God, when she remembers who she is, expects more than the pig-scrap life. She begins to long for the biggest kind of life. That’s the first step. At the end of 40 years of wandering in the wilderness on the way to Promised Land, Moses says to the children of Israel, “God humbled you by letting you hunger, then by feeding you with manna, bread from heaven, in order to make you understand that one does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of the Lord.” This is the second step into the biggest kind of life. I was not made only to go grasping after the things of this world. Yes, I have to eat. But there’s an even deeper hunger within me. And to honor that hunger I eat every word that comes from the mouth of my God, I take the bread of life not into my belly but into my heart. I align my life to God in the same way that God has aligned herself to my true life. Yes, I still eat bread. But that is no longer my function. I am no longer a consumer, a grasper, a hoarder. I’m a believer, a giver, a careless sower of seeds—I scatter them all over the place, I don’t judge, I don’t discriminate, I don’t hide my light from anyone because I believe that transformation is possible everywhere and all the time! Here, in the biggest kind of life that Jesus offers us, we become aware of the profundity of the grace that has saved us. What a gift we’ve been given! We recognize that no amount of our own effort could have ever resulted in such life, such freedom, such love. And yet, simultaneously, I recognize that without my effort, this gift of grace is absolutely wasted on me because I, I, I must realize that I am a child of God, who does not live by bread alone, who has been given an incredible gift, who has aligned the core of my belief to the Gospel, and who will continue the work of announcing good news to the poor, bringing the Kingdom of God to earth, and expecting transformation all around me. When Jesus says, “Very truly, I tell you, whoever believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life,” I think about my own death—my dying one day. I hope in that moment that I will be ready to come fully alive. I hope that come that day, whatever is left of my ego and my way will be finally ready to retire completely. I hope I will have long ago left behind my demands on God for my life. I hope that when I turn my eyes to God, I feel eternal life around me already. I hope that I pray, “God, I’m ready for you to change everything again.” Last Sunday Jesus fed 5,000 people with five small loaves of bread and two fish. The people were so impressed and so pleased they tried to take Jesus by force and make him their king. But Jesus wasn’t interested in being king. So, he ran off. Now, he’s on the other side of the Sea of Galilee. But the crowd hasn’t given up. And they find him on the other side of the lake. Hey, man, we’ve been looking for you everywhere! What’d you run off like that for?

And there was a woman in that crowd. And she stepped forward. If you had seen her, you would have seen a woman dressed plainly, with patches where her bony elbows had worn the through the fabric of her shirt. She held her head up high, and she had a spark in her eye that warned of an intelligence far beyond what the world expected of her. So, she lifted up her voice for everyone to hear and spoke to Jesus. She said, “Yesterday, we ate our fill of miraculous bread! We were stuffed and happy! For a while we forgot our cares. (And you know what heavy burdens so many of us carry.) We laughed, and we played with our children on the grass. And when the sun set, we rolled ourselves up in our picnic blankets, and we slept under the stars to the sound of a distant storm passing us by. But when we woke up, our stomachs were empty again. You were nowhere to be found. And we were all saying to one another, ‘Why? Why am I still hungry?’” Jesus is ready for the crowd. He expects them and this question. And this is Jesus’ way: Yesterday he had compassion for the crowd. He fed us, he comforted us. Today his compassion will challenge us. Yesterday there was overflowing, miraculous grace! Today Jesus will challenge us to respond to that grace. We’re all very aware of this dynamic in our tradition. It’s often put into words something like this, “As we have been fed, let us go out now and feed others.” The proper response to grace received is action that reflects and furthers that grace. This goes all the way back to the beginning of our Bibles. After delivering them from slavery in Egypt, God gives this command to the Children of Israel at Mount Sinai: “You shall not wrong or oppress the stranger. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the stranger as yourself, because you were once strangers in the land of Egypt.” They are delivered from bondage by God’s grace, and now they carry the burden of honoring that grace in action, in law, and in responsibility. We know this already: The first step is grace, the final response is action, productivity, justice, etc., etc. But did you know that there’s another step between the initial grace and the final response? It sometimes gets forgotten. What is it? The crowd makes this mistake—they leave this step out. They are so eager to be full again. They want to be in control. They tried to make Jesus king—that didn’t work. Now they ask him, “What must we do to perform the works of God?” In the Greek they literally say, “What must we do to work the works of God?” These people want to get to work! But there’s a mistake here. They want to work God’s works in order to get more of God’s grace, more bread. They’re not responding to grace; they’re attempting to manipulate grace. But that’s not how grace works, and it’s not how the response to grace works. There’s a missing step. What is it? And, we should say, work is not what Jesus is looking for here. Jesus doesn’t ask the crowd to do anything, right? In fact, he tells them: Do not work! Do not work for food that perishes. Instead of asking them to work, he makes them yet another offer—an offer of food that endures for eternal life. This is the work God requires of you now, Jesus tells them, to believe in the one whom God has sent. The step between the receipt of grace and the works of grace is to believe. The crowd runs into a problem here. There’s a man who pushes his way up to the front. If you had seen him, you wouldn’t have noticed anything much about him. He could have been any person walking past you on the street or sitting next to you in these pews. But the way he crosses his arms over his chest before he speaks—you would have noticed that. There’s strength there, but also pain, like someone who has faced hurt, who is on his guard. He crosses his arms over his chest, and he says to Jesus, “Believe in you, you mean? We might. We might do that. But, of course, we’d need a sign from you. After all, when our ancestors were led out of Egypt into the wilderness by Moses, wasn’t there bread from heaven on the ground every morning for forty years so that they wouldn’t starve? Every morning! Now, that’s a dependable schedule! If you could give us a little more of that miraculous bread of yours (on a reliable schedule), I think that’s the sort of thing that would put us on the path to becoming true believers!” We make our belief contingent on the circumstances of our lives. We all want a sign that we’re on the right path. And we can’t think of a better sign than being perfectly cared for, cocooned from all the hardships of this world. No matter how much grace we receive today, there’s always tomorrow to worry about. Today we feel like believers. But tomorrow—well, we’ll see. Even more than the crowd, we modern people don’t know anymore what it means to be a true believer. We don’t even really understand what Jesus is asking of us. I’ve got a friend whose little daughter called her into her bedroom. “Mommy, mommy, come quick!” When she rushed into the room there were a pair of scissors lying on the floor, and there was a great, big, giant bald spot on the front of her daughter’s head, and there was a great big clump of her daughter’s curly blond hair in the wastebasket, and (as will become relevant in a moment) all the windows were closed. And her daughter said, “Mommy, a bird flew in through the window, landed in this wastebasket, and all its feathers fell out. Then it flew back outside!” “Oh,” my friend said, “I see. And who opened the window?” Her daughter thought for just a second, and then she said, “Oh, it must have been God.” Our world mistakes believing in God or in Jesus with assenting to (“believing in”) a difficult and complicated story that doesn’t always make sense. That’s what my friend’s daughter was asking her to do. But that is not what Jesus is asking of us. The postmodern world hears that we believe in God, and it reduces that belief down to a caricature: We think there’s a man with a beard in the sky who can open and close windows from heaven. But that is not what Jesus is asking of us. True belief in Jesus is a commitment to a way of being throughout our lives, a total fidelity to the good news that Jesus carries within himself. It’s not about did Jesus exist or not. Did Jesus say this or that or not? Did Jesus do this or that or not? What do you think about it? Do you believe that? No. The real question is: Am I permanently attuned to God through Jesus Christ? Am I aligned to the Gospel Jesus brought? Am I committed to the values Jesus taught? As I said last Sunday, Jesus feeding the 5,000 was the miraculous demonstration of an almost incomprehensible truth: that God aligns the abundance of heaven with the scarcity of earth. What grace! What incredible grace! And now a response is required. Since God has aligned heaven’s abundance to our needs, Jesus is asking us to acknowledge this grace by aligning our innermost core (our belief) with the Gospel. Belief in Jesus means becoming a devotee of the religion of Jesus, turning ourselves over entirely to God and to God’s purposes. We sometimes think that all belief requires is an expression of our assent. You could turn off your brain, and it might be easier. But what is really being asked of us is to offer God the beating heart of our consent. And that is a commitment wrought hard out of every moment. God doesn’t want words or thoughts or even deeds. God wants me—all of me and all of you, right down to our motivations, our purposes, the meaning of our lives. We confuse physical and spiritual needs. “Why am I still hungry?” I must need more bread. But that's not the way spirituality works. A lifetime of bread from heaven won’t satisfy our deepest hunger. The opposite doesn't work either. We can't be saved by our own hands. We can't earn our way to salvation. No amount of good living will open the gates to God’s Realm. So, then what are we supposed to do? We do not consume God, we let ourselves be consumed by God. We do not do the works of God, we become the works of God. That is what is meant by belief. And that is the missing step between receiving grace and changing the world. Until we believe, we will always be saying to ourselves, saying to one another, “Why? Why am I still hungry?” God’s grace will not quiet that hunger. It merely whets the appetite. Through our good works we may attend to the physical needs of others, but we cannot quiet our own deepest hunger even in the performance of righteousness and the pursuit of justice. We will always be hungry until we hold in the center of our hearts the bread of life that Jesus is offering. Beloved, are you still hungry? Poet Thomas McGrath wrote, “We know it is hunger—our own and other’s—that gives all salt and savor to bread. But that is a workday story and this is the end of the week.” Beloved, my prayer for you is salty, savory, end-of-the week faithfulness, where God can hold you tenderly, like bread in the palm, in the sweet spot of belief, floating steadfast in the tension between grace and responsibilities. Amen. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed