|

A few weeks ago, my four-year-old son Romey asked me, “Dad, are bees dead?” Romey’s been very curious about death recently and learning a lot. Romey, who loves gardening and the outdoors, hadn’t seen any bees all winter long and he was beginning to get worried. I put his mind at ease. I explained to him that some bees do die in winter, especially if it’s very cold, but if all the bees were dead, there wouldn’t be any more bees in spring. I told him that bees were just hibernating the winter away in their hives or in piles of leaves and in old dead logs waiting for the warm weather to wake back up.

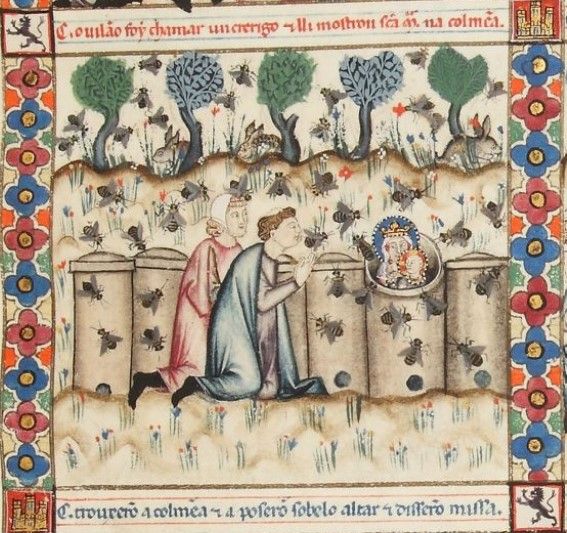

On April 8, 1966, Time magazine published one of its most iconic and maybe infamous cover photos of all time. It was a first of its kind cover—just text; three red words on a black background asking a question: Is God Dead? It set off a firestorm of overwhelmingly negative responses. Letters poured in. Pulpits across the country thundered. Even Bob Dylan would criticize the cover in an article in a magazine the illustrious name of which I can’t say with kids in the room, but let’s just say there was a bunny on the cover and she sure wasn’t the Easter Bunny. Time magazine and its editors were labeled from all sides as atheists, communists, anti-American. The article itself was far tamer than its headline suggested. It was all about the changing state of religion, religious sensibilities, and theology at a turning point in American history—the post-World-War-II religious revival had peaked, the Cold War and nuclear annihilation had seized the world and our apocalyptic imaginations, the Civil Rights movement had presented a new idea of the power of religion to transform society for the better, the war in Vietnam was beginning to cause serious unrest, the flower-power, psychedelic, hippie movement was in full swing, and a month earlier John Lennon of the Beatles had told the world, “We’re more popular than Jesus now.” In this moment, the article fairly evenhandedly laid out the questions that religion and faith were wrestling with. But people hated that cover, they hated the question it asked, and they hated anyone who would ask it. Death of God theology, which is a real thing (it’s also called radical theology), was barely more than a footnote in the article, but one of the theologians referred to as a death of God proponent in the article, William Hamilton, was turned on by his community—he was driven with his family from his church and he was forced out of his job as a seminary professor. Something about this question, “Is God Dead?” made people feel vulnerable, anxious, and really angry. Now one of the great ironies of this to me is that April 8, 1966, the day the cover was published, was Good Friday. I’m sure that was intentional. What day could be more appropriate to sit with this question than the day the of crucifixion, the day that Christians believe that God, in some sense, actually died. Even people who believe that God died were not ready to be asked the question, “Is God Dead?” which I find striking. The reason I’m talking about Good Friday on Easter morning is because our understanding of the resurrection depends on our understanding of what happened on Good Friday. Just like we’re uncomfortable with questions like, “Did God die? Is God Dead?” We’re also uncomfortable with Good Friday—for good reason: It’s bloody, it’s violent, couldn’t God have found another way? Most Christians go straight from Palm Sunday to Easter skipping Holy Week and the crucifixion all together, skipping the possibility of being asked the uncomfortable questions. For most of us, I think, we’re willing to admit that God is an occasionally hibernating God. Just like the bees, sometimes God seems to disappear, but God (for good reasons that we can’t fully understand) is just napping in a pile of leaves somewhere and will be back in due course. The nice thing about this kind of resurrection is that it’s just like spring: the blossoms on the cherry trees are same year after year, and when the bumblebees come back they act like bumblebees have always acted, and when the tulips come up from the ground, they come up exactly where you planted their bulbs. Spring is reassuring and predictable, and we can forgive an unchanging and predictable God for occasionally going dark on us. And we prefer this hibernation faith to a resurrection faith that says that our God is a continually dying and rising God—our God has died, and our God has risen in a way that we barely recognize. Mary Magdalene, in John’s gospel, met the risen Jesus in the garden and didn’t even recognize him he was so alive and so transformed. Maybe Jesus was playing a joke, we think. Maybe he found the gardener’s hat and put it on to pull poor Mary’s leg. Maybe she just needs glasses. How different could he have been? He was just in there a couple days. Resurrection is a total transformation because death, first, is a total transformation. Now I don’t agree with everything that radical theologians say. They say all kinds of different things. I disagree emphatically with some of it. But I deeply appreciate the kinds of questions that they ask. Essentially, what they’re asking us is: In a world even more radically changed than when that cover was published more than 50 Easters back, are some of our ideas about God, some of our images of God “stuck” in the ideas, images, and values of an earlier age, a by-gone culture. If we can’t let go of some of that stuff, if we can’t even be asked the questions without attacking those who ask them, how can we ever live fully into a resurrection faith? Resurrection isn’t a destination. It’s not a one-time event. And its not just about Jesus. The Bible tells us that resurrection is the destiny of all who believe and it’s the destiny of all of creation. The resurrection is a new spiritual dimension and a continual process. It’s not everything that God was, continuing on. It’s everything that God is, now becoming. It’s everything we are, now becoming. In the article, Is God Dead?, various people were asked about their images of God. One man from Philadelphia said that he sees God “a lot like he was explained to us as children:” an older man up in heaven who is just, but who gets angry at us. “I know this isn’t the true picture,” he said, “but it’s the only one I’ve got.” This man feels it. He feels that he’s stuck, but he’s afraid of betraying the image that was given to him as a child. He wants to grow his image of God, but he doesn’t know how to grow an image which he knows isn’t the true picture, and he doesn’t know how to let it go. He’s stuck. And God is stuck with him. Many people in his situation will stay stuck. Many people realizing the limits of the culture’s ideas about God will throw the baby out with the bathwater and get rid of religion and faith all together. What will you do? I also was raised with this image of God: a nice man in heaven who made everything and controls everything and doesn’t change. In High School I had a couple of experiences that began to challenge this view. One of them was learning about evolution in my biology classes. I was totally fascinated by this process which was nothing like the creation story that had been told to me. In my fairly Evangelical youth group, we had a debate on Creationism vs. Evolution, and I was on the much smaller Team Evolution. I studied for this debate for weeks. I was so into it. I read like five books on evolution and made notes and I was ready to rumble. But I was, I must admit, uncomfortable. If evolution was true, what would that mean for God? When I got home the night of the debate, feeling victorious despite the fact that my wise Evangelical youth pastor didn’t declare a winner, I realized that in the course of this experience, for me, the unchanging God who created an unchanging universe and mostly unchanging life exactly as it is 4,000 years ago in the book of Genesis was dead. But, thank God, my faith (probably because of that youth group and the opportunity to talk about evolution in it) was not dead! I opened those books on evolution again that night in my room and marveled at the God who was now suddenly able to come to life in those pages—a God who was at the heart of a continual process of change that is growing the world—the universe. I experienced a resurrection that night. God was transformed before my eyes, and I was lucky I could still recognize her there growing, changing, randomly and yet with what appeared to me then as some sort of greater purpose that has not yet been completed. And it is still ongoing on the biggest and smallest scales. You see, beloved, if we truly live into our resurrection faith, then we may at times feel like the women running from the tomb at the end of Mark’s Gospel, full of fear and awe for what is coming, afraid to say anything. But when we realize that God’s death and resurrection is the new way, the new image of what God is doing in our world and in our lives, we may discover God’s true, vibrant limitlessness. Is God Dead? I say, yes, God died on the cross. And now God is resurrecting, rising beyond our expectations, showing us the infinite potential in our lives and in our world. This Easter let’s celebrate the resurrection by committing ourselves to harnessing and guiding the power of radical change in our lives and in our world. We can’t stop change. But we don’t need to fear it, as long as we are willing to let God come back to life within it. That is a resurrection faith.

0 Comments

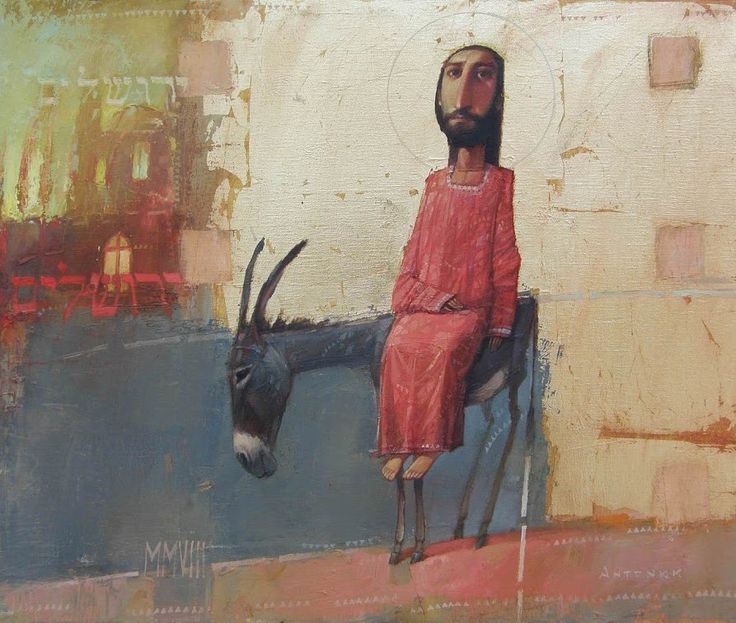

Preaching on: Matthew 11:1–11 The rise of Christianity is just about the most improbable origin story imaginable. The biggest religion in the world today and the biggest in all of human history was founded by a poor, peasant rabbi who was a part of a tiny backwater religion, which had been conquered and subjugated by one of history’s greatest empires—Rome. And that poor, peasant, Jewish teacher was crucified by the Roman Empire—a contemptible, shameful public execution intended to utterly wipe out his legacy. And within 300 years of his death on that Roman cross, Jesus the Christ would become the God of that empire. And the image of him, staked out and dying on their cross, would become ubiquitous and holy to them. How was such a reversal possible?

It must have been God’s will. Well, sure. But that doesn’t tell us anything about God’s technique, God’s style. The thing about being omnipotent is, you always have plenty of options. To be honest with you, I’m not so sure about thinking of God as omnipotent—ALL POWERFUL. If I were all powerful, I think I might behave a little differently than God does. If God is all powerful, I think it’s safe to say that God isn’t a showoff about it. And, in fact, we can see God, the almighty God, beginning to show contempt for what we humans think of us as power. How would a God who is all powerful, but who is coming to loathe the expression of that “power”—violence, war, subjugation, oppression, exploitation—how would that God behave? Perhaps if you were all powerful, but you had come to regret what power is and how it works, you might decide to redefine what power is—to redefine yourself. Maybe you would come down from “on high,” enter the world a lowly peasant, and conquer an empire not through a decisive military victory but with nothing more than the persistent power of your symbolism and the gradual spread of your love. In a world dominated by the fist and the whip and the legion, perhaps you too would wield healing, compassion, and forgiveness as the truest forms of strength. And where power raised an army, rode a war horse, and took itself very seriously indeed, perhaps you too would call disciples, ride a baby donkey, and mock the very power the world has come to believe that you are. And so we come to our parade this morning, Palm Sunday, the entry into Jerusalem. First, you have to understand that it’s very possible that on that very day and perhaps that very hour that Jesus rode into Jerusalem down the Mount of Olives that Pontius Pilate, on the other side of town, was also entering Jerusalem in force, on an armored horse, surrounded by legions of soldiers in a stark display of intimidation and (as always) with the inherent threat of violence—you people had better not get out of hand at this year’s Passover. Jesus’ parade was not just different than Pilate’s, it was a mockery of Roman power and all “power” that lives and dies by the sword. On May 26, 2007, members of a white supremacist hate group held a march and rally in a public park in Knoxville, Tennessee. The counter protesters were sick and tired of the Antifa tactics sometimes used to shout down (and sometimes beat down) white supremacists. It felt like they were getting sucked into the very display of violent power that they were wanting to oppose. How do we still stand up against them while offering an alternative to them? Instead of meeting anger and hate with more anger and hate, they decided to meet them with humor. And so the Coup Clutz Clowns were born. When the neo-Nazis marched, the clowns marched with them, only they made sure to goose step in their floppy red shoes. And when the neo-Nazis shouted, “White Power!” the clowns pretended like they couldn’t hear them very well. The neo-Nazis shouted louder, and then the clowns understood. They started throwing handfuls of flour into the air and shouted “White Flour!” Some women arrived in their wedding dresses and corrected them, “No, No, No, not ‘White Flour,’ ‘Wife Power!’” A clown on stilts with a tiny little handpump camp shower started spraying water onto the clowns below. They all tried to squeeze under the tiny stream of water, but there wasn’t nearly enough room. “Tight Shower!” screamed the clown on stilts. “Tight Shower!” And the neo-Nazis decided to go home. Now Jesus wasn’t just clowning around on Palm Sunday. He was, I think, deadly serious. His “Triumphal Entry” into Jerusalem was a mockery of Roman pomp and power, but it was also a true and serious display of God’s new definition of power: humility, sacrifice, the commitment to peace, and the certain knowledge that “power’s” greatest threat—humiliating torture and death—could be converted into the greatest expression of commitment, love, and transformation that the world had ever known. As Jesus enters Jerusalem on a baby donkey, he is locking on to his fate. There can be very little doubt that he knew that mounting that tiny donkey and riding down that hill would lead him irrevocably to the cross. There is no turning back now. He knew where his actions would take him—to the cross and to a holy transformation of the very idea of power. He was utterly rejecting the traditional hope (an almost hopeless hope) of a violent, revolutionary messiah who would raise an army, ride a war horse, call down the legions from heaven, and defeat Rome in battle. If God is all powerful, couldn’t God have done it easily? Of course! When I read my Bible don’t I read many stories about God using power in just this way? Doesn’t God use death and suffering to humble the proud and punish the wicked? Yes! Doesn’t God use war and violence and subjugation to win territory for God’s chosen people? Yes! But in Jesus Christ, beginning with Christmas and concluding with Palm Sunday and Good Friday, God is choosing to no longer conquer the world from on high. Instead, God will transform the world and all those on it from within. As Christians, do we understand what Jesus has taught us? Do we understand that the Kingdom of Heaven that we were expecting from on high has actually arrived as the Kingdom of God within us? Do we understand that the power we are still most enamored by (the power of coercion through force and domination), is no longer the greatest power in this world? Because we still cling to it, looking to it for assurance and security, forgetting that every empire in history has fallen, that every wall ever built has been breached, that every army ever raised has ultimately been scattered. Do we understand? And are we willing, as we wave our palm branches and shout our Hosannas, are we willing to explore in our lives, in our world, the kind of power Jesus demonstrates? The power of the Mahatma Ghandis and the Mother Teresas and the Martin Luther King Jr’s and the Dorothy Days and the Nelson Mandelas of this world? The kind of power that is far too weak to conquer the world but is the only kind of power strong enough to transform the world. What would it look like to expand upon that true and great power in your life? What would it feel like to loosen your grip on this world, on your life, and give yourself to this world and to the people around you instead? What if your greatest fear wasn’t dying, but was not taking the necessary risks in this life to become everything God intends you to be—no longer frightened and clinging and cruel, but confident and expansive and full of love? By this power, Jesus and a few disciples conquered the greatest empire in history! What could we achieve if we were willing to follow him? “Very truly, I tell you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain, but if it dies it bears much fruit.” What a strange illustration—to imagine a death and burial as a seed being planted in the ground, and connecting these two concepts which seem to be total opposites: death and growth. Are death and growth really connected? What does Jesus mean?

The simplest way to interpret this profound statement is to explain it away. It’s obvious what Jesus means, isn’t it? He’s talking about himself—his impending death and coming resurrection, which are unique to him alone. But that ignores what Jesus is actually saying here. He’s not saying, “I am the seed…” What’s so startling about Jesus’ words here is that he’s making a universal argument based on natural principles. Yes, he’s talking about his own coming death, but he’s framing it as an example to us of something that is more broadly true of all creation. On Friday night, John and Janet Dobbs hosted an event for the Ministry of Adult Education. The topic of discussion for the evening was suggested and very ably introduced to us by Rita Ellertson—the recent Alabama Supreme Court ruling that frozen embryos in test tubes should be considered children and the very real fallout for people and families undergoing In Vitro Fertilization treatments in that state. Essentially, if embryos are children, there can be no IVF because being an embryo is so inherently risky. Just to be clear—an embryo is not a fetus. The frozen embryos ruled to be children in Alabama are at the earliest stages of development—something like six to ten cells. It’s estimated that 50% of embryos don’t make it in natural human reproduction and the odds may be worse in reproductive medicine. Declaring these little fragile miracles to be little fragile children, means no one can risk making a miracle with them at all. As the conversation delved into the broader societal understanding of when life begins and the state's role in regulating reproductive health, many of us struggled. Calling an embryo a child seemed to go too far but calling an embryo a piece of property seemed to be missing something. Treating the six to ten cells of an embryo no differently than six to ten cells off your elbow seemed unacceptable but calling a freezer full of embryos a “cryogenic nursery,” as the Alabama Supreme Court ruling did, seemed absurd. If we think that embryos are special, even sacred, but then don’t protect them from all harm, are we just hypocrites? I don’t think so. Throughout his ministry Jesus recognizes the sacred fragility of life. Why is life so fragile? Why is it so easily lost? We can’t answer that question, but we have recognized over the millennia that the fragility and fleetingness of life is strangely part of what makes life so worth living. Why are embryos so fragile? Why are so many lost? We can’t answer that question. But we can recognize that our desire to protect them from being lost could lead us to protecting them from actually living. Of course we’re emotionally invested in them. Of course we’re rooting for them. Of course we’ll protect them from truly bad actors who don’t recognize them for what they are. But we cannot protect embryos from their own fragile destiny—from life. Trying to make it in this world is always a risk. Embryos are sacred to me not because they’re children, but because they’re embryos—fragile little miracles carrying the hopes of new life risking everything for the next generation. Sherry Brabham, on Friday night, made the point that we focus so much on the virtues and beauty of creation in the Christian tradition that maybe we don’t leave any room for the possibility of the sacredness of destruction and death as a part of the process of creation itself. When Jesus told the disciples he would be crucified, Peter rebuked him. Don’t say that! You’re sacred! Sacred things must be protected! Jesus rebukes Peter right back. You have your mind on human ways, not on divine ways. It’s a human tendency to want to preserve the sacred from destruction. But from a God’s eye point of view, sacred things must fulfill their sacred purposes—and (though we don’t think of it much in Christianity) perhaps even destruction and loss and death have an important and even a sacred role in creation, in life, in reproduction. A religion that maybe has a lot to teach us about the theology of destruction is Hinduism. In Christianity, of course, we have a Trinity: God (the creator), Christ (the redeemer or savior), and the Holy Spirit (the sustainer). In Hinduism, there’s a Trimurti of Brahma (the creator), Vishnu (the sustainer), and Shiva (the destroyer). So, in both the Trinity and the Trimurti we have the concepts of creating and sustaining. But the third concept is different. Christianity has salvation (through Christ) and Hinduism has destruction (through Shiva). But could it be that these are just two different perspectives on a larger, unified concept? Shiva’s destruction isn’t just annihilation but a necessary precondition for renewal and regeneration. Through destruction, Shiva paves the way for a new cycle of creation. And Christ's salvation came through an act of destruction (the crucifixion), which led to a renewal and regeneration (the resurrection). The imagery of the crucifixion makes us very uncomfortable. Many of us feel like if God is all powerful then God could have found another way to save the world other than through a brutal execution. We want from God the version of life where everything is always on the up and up—always growth, never destruction; always success, never loss; always resurrection, never death. Why are 50% of embryos lost? Why so much waste? Why so much destruction? Why did Jesus tell us he had to be crucified? Why such violence? Why death? We can’t answer those questions, but we can hopefully come to recognize that these are inherent truths of life we love—that reproduction requires risk, that living requires dying, that resurrection requires crucifixion, and that creation, salvation, and destruction are intimately connected. Hoping for exceptions to these rules or trying to make the law reflect our human desires rather than God’s ways denies the beauty of the fragile, sacred, miraculous lives we are living. Romey, my four-year-old son, has been asking questions lately about death—kind of skirting around it, trying to figure things out. He was asking me some questions yesterday while we were snuggling at bedtime. And I asked him, “Honey, are you afraid of dying?” And he said, “I am NOT telling you!” “Why not, honey?” “Because it’s too scary, and if something is too scary, you don’t talk about it.” Oh boy. And so I told him, “No, honey, when you’re having big feelings, that’s when it’s most important to talk about it because that’s how you deal with those feelings. That’s how you learn. That’s how you grow.” And (miracle of miracles) my four-year-old (going on 14) actually decided to talk to his old man about something. And in the course of that conversation, I suddenly got scared. I was suddenly initiating my son into the realty of life and death. I felt his innocence slipping away. I wanted yell, “STOP! Save him from the knowledge of death! Save him from the reality of death! Save him from death!” But if I had done that, it wouldn’t have saved him at all, it just would have left him afraid and unable to grow. He had to confront death. And his innocence—maybe this is a bit dramatic, but in a sense, it needed to die a little on this topic in order for him to grow up a little and live a little more wholly without being afraid. I was telling him the story of the night my mother died. And he asked me, “What did Grandma look like when she died?” And I said, “Well, I took a picture of her after she died, lying in the bed,” and I immediately regretted it. “Can I see it?” he asked. I took the picture because I wanted to remember the sacredness of that moment for my family and for my mother. It was sad and tragic. It was death. But it was sacred. And it didn’t feel like the end. It felt like a beginning for Mom and for all of us. “Are you sure it won’t be scary?” I asked him. “I’m sure,” he said. “I want to see it.” And I knew he needed to see it now in order to not be afraid. So, I showed him the photo. He asked me to zoom in on her face. I did. I held my breath. “Is it scary?” I asked. “No, it’s not. Now can I see a picture of Grandma breathing?” And so we lay together snuggling in bed flipping back and forth between pictures of my mom when she was alive and the picture of her just after she died. And I felt my son growing in my arms. Death and growth truly are connected. From the very beginning we risk everything to be here. And the challenges we face, the innocence we lose, and the sacrifices we make to keep the great engine of creation and life turning are what is truly sacred. Amen. John 3:16, is traditionally rendered, “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” It’s one of the most famous and well-known verses in all of sacred scripture. Love, generosity, salvation! John 3:16 invites us into an expansive vision of salvation—one that is inherently "Bigger Than Me." But we worry about the perishing part.

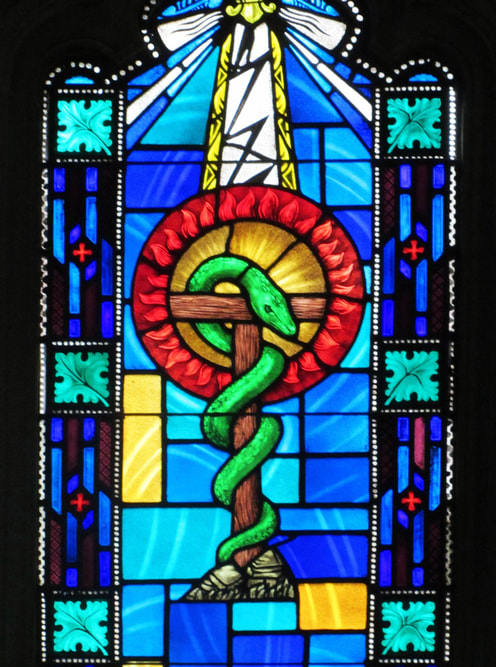

“That whosoever believeth in him should not perish” can all too easily be flipped around to say, “that whosoever believeth not in him should perish, will perish, is already perished!” And we worry about our Jesus, who is supposed to save the world with love, becoming the one who somehow casts the vast majority of the human race into the eternal firepits of hellish damnation that have so captivated the febrile imagination of the Evangelical movement. Have you heard the story of “Rock’n” Rollen Stewart? Beginning in the early 80s, “Rock’n” Rollen Stewart, also known as “The Rainbow Man,” would strategically buy tickets to major sporting events where he was sure that he’d be in the background on a lot of the televised shots. He would wear this rainbow-colored afro clown wig, he’d hold up a big JOHN 3:16 sign, and make as much of a nuisance of himself as possible—jumping up and down and waving his signs around whenever the camera was on him. When people asked why he did it, he simply said he wanted to get the word out. But in the early 90s, after a number of tragic life events and believing that the Final Judgment was imminent, “Rock’n” Rollen Stewart began terrorizing churches he disagreed with by stink bombing them. He began mailing out “hit lists” filled with the names of preachers he disagreed with, and he didn’t sign them “The Rainbow Man,” he signed them “The Anti-Christ.” Then in 1992 he used a gun to kidnap two day-laborers and a hotel maid. He ended up barricaded in a hotel room holding the maid hostage. The police were outside the room shining these big, bright lights through the windows. And Rock’n Rollen (this is for real) used his JOHN 3:16 signs—he taped them up in the windows—to block out the light. The very same signs, and the very same verse, meant to bring light into the world and to invite the world into salvation, were now being used to hide in the darkness, to shut people out, and to condemn the world. And so some of us worry: Is John 3:16 an invitation to the good news or is it a sort of stink bomb—or worse? We worry because we know how much harm the Jesus who condemns people can do. And at the same time, we know how powerful and good salvation can be. In 2018, I heard a speech given to New York City faith leaders by Matthew McMorrow. McMorrow is a gay activist and at the time he was a senior advisor to the mayor’s community affairs unit. When he came out as a teenager his family didn’t accept him, his friends didn’t stick by him, and the faith community where he served as an altar boy made it clear that he was no longer welcome there. McMorrow had been condemned. But at some point, he met a Lutheran pastor who told him, “Matthew, God loves you just as you are.” And McMorrow told us with the relief still in his voice, “Those words SAVED my life.” And hearing that story we know that being saved is good! And we can’t believe it leaves anybody out. Acknowledging that the embrace of God's kingdom is "Bigger Than Me" means that it may well be bigger than my current understanding. And if it’s true that people who don’t believe the perfectly right things in the perfectly right ways are already condemned, then I am more certain than I am of anything, that I am one of those condemned people. Because I do not believe “perfectly.” I’m a doubter. And to be honest I like it that way. Remember, Jesus taught us to be humble. And humility and doubt allow us to grow our faith commitment in ways that are not possible for “perfect” believers. The Bible teaches us, “do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world.” Belief alone can never teach us this kind of discernment. Discernment requires doubt, it means taking nothing for granted, it means interrogating every good idea and venerated dogma. Jesus said that the wheat and the chaff must grow together in the same field. That means you’re never going to find a wheat field that doesn’t have at least a few weeds lurking around in it somewhere. We typically interpret this parable to be about people. Some people are wheat and some people are weeds, and one good day God will harvest the field and send the wheat-people to heaven and the weeds-people to hell. But I think this parable is about beliefs. Some of my beliefs glorify God and some of them don’t. And as long as I’m alive, I better remember: I’m not always right. Christians are the ones who acknowledge their weeds and knowing we can’t tear them all out, we have to at least be able to recognize them. For example, there’s not time to discuss the full history here this morning and all the reasons for why and how it happened, but the Gospel of John is a very anti-Jewish text—frequently condemning those Judeans or Jews who don’t believe in Jesus. And that condemnation in our holy scripture has given rise to a terrible shadow. John’s Gospel has been used to incite, justify, and perpetuate antisemitism for more than a thousand years. And so, we (as Christians) don’t get to take the easy way out. We don’t get to simply take the plain sense of the text without looking too deeply into the shadows we cast. We don’t get to scoop up our salvation and leave the rest of the world to be damned. We must find the courage to discern. And Jesus gives me that courage and that example. Jesus said, “just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Human One be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” Jesus is referring to a gem of a story from the Torah about God getting sick of the Israelites complaining in the wilderness. God decides to teach them a lesson by sending poisonous snakes to bite them. The quickly repentant Israelites, dropping dead from snake bites, ask Moses if there’s anything he can do. So, Moses prays to God and God tells him to cast a bronze statue of a serpent and to put it on top of a pole. Whenever anyone is bitten, all they have to do is look at the bronze serpent and they’ll be healed. And that’s what Moses does. And anyone who gets bit by a snake on the ground can be saved by looking at the snake on the pole. It’s an interesting story. You’ve got to wonder why God didn’t just make the snakes go away so that nobody would be bitten anymore. Well, snakes had two very different reputations in the ancient world. They were a symbol of death and evil for reasons we still understand today. But they were also symbols of healing and resurrection because of the way they shed their old, dead skin to reveal a shiny, healthy skin underneath. It’s almost like the story of the snake on a pole is trying to tell us something true about the world: there are snakes in the world that can kill you, and there are snakes that can heal you. And Jesus says, “Yeah! I’m that snake—the healing snake lifted up in the wilderness. I wish I could just snap my fingers and make all the toxic and poisonous versions of God’s love that are slithering around in the world go away. But I can’t. I can only lift my true self up with love in the hope that I can heal those who have been bitten.” Beloved, keep your eyes peeled for snakes. They’re out there! But don’t be afraid to lift up the One who heals with love. I think that many of you have met that Jesus. And he’s offering himself as a gift to the whole world—to every person, no matter how or what they believe, no matter what evil thing has latched itself to them. Don’t be afraid to lift your Jesus up higher. Recently, a buddy of mine, Rev. Michael Ellick, out of Seattle, preached a sermon that inspired me to write this sermon. So, thank you, Michael.

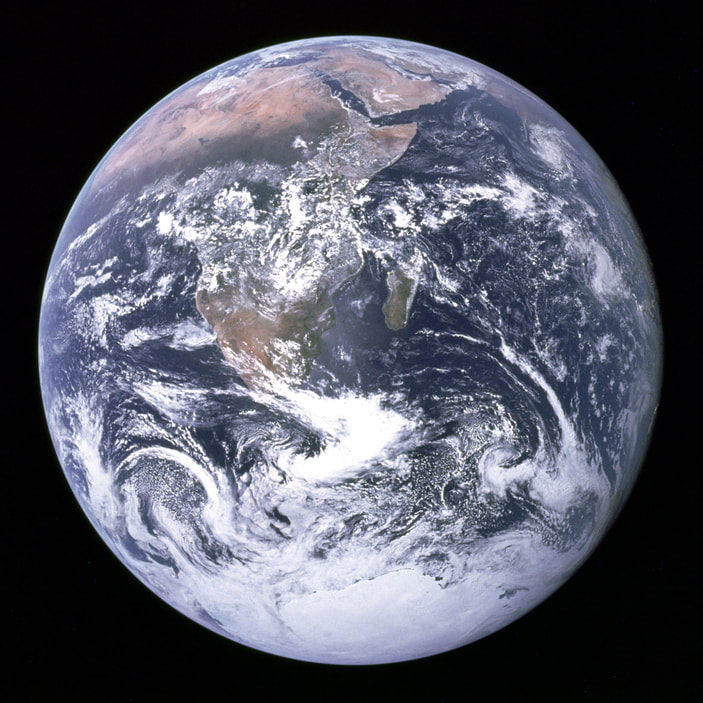

I think most of us probably have some sort of understanding that nature is closely connected to spirituality. Most of us have probably had an experience of walking in the woods and feeling a profound sense of inner peace and interconnection to the web of life all around us. Or of being struck by the beauty of some breathtaking mountaintop vista and suddenly all the chatter in your mind quiets down out of respect. Or at 5 a.m., before the world has begun to bustle, the reddish light of a summer sunrise suffusing the moist air of morning seizes your imagination and the whole world seems suddenly alive and filled with magic. But Psalm 19 ask us to go further than all that. Psalm 19 tells us that knowledge about God is being declared by God’s creation. The heavens are telling the glory of God! Day pours forth speech; night declares knowledge. BUT there is no speech, no words, no voice is heard—yet their voice goes out through all the earth and their words to the end of the world. What kind of knowledge can only be communicated without words? Well, this morning there’s a visual aid for you on the cover of your bulletin. This photo was snapped by the Apollo 17 mission on its way back home to Earth. It’s called Blue Marble. This wasn’t the first photograph of the Earth taken from space. Other famous photos, like Earthrise (a photo of the Earth rising in the inky blackness of space above the moon’s surface), came before it. But Blue Marble was the first perfect portrait of our home planet from an outside perspective. It balances the viewpoint of the Earth being nothing more than what Carl Sagan famously called “a pale blue dot” in space with the ability to instantly recognize “the face” of our home. And so it became one of the most influential photographs of the 20th century. It became an icon of the fledging environmental movement. But it represents, I think, an even larger cultural shift in perspective that is only just beginning. Only about 600 people so far have been to space. And while the photos are powerful and have had a profound impact on our understanding of our planet and our place on it, from what I understand, the photos pale in comparison to the actual experience of seeing the Earth first-hand from space—which according to many astronauts is a life-changing, consciousness-shifting, spiritual, mystical experience of the highest order. The experience has been called “The Overview Effect.” Basically, when the Earth is seen from an outside perspective, when all of nature, and all of humanity, and the location, the setting of everything we have ever known or done all comes into view and can be taken in at a glance, a new knowledge—the kind of knowledge which is totally and utterly beyond the ability of words to communicate—is experienced. Astronaut William Anders (who captured the photo Earthrise) said about his trip to the moon, “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.” Astronaut Russel Schwiekert said, “When you go around the Earth in an hour and a half, you begin to recognize that your identity is with that whole thing… and that makes a change… it comes through to you so powerfully.” Astronaut Edgar Mitchel, who ranked seeing Earth from space as the most important and influential event of his life, said, “You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it.” Neil Armstrong said, “It suddenly struck me that that tiny pea, pretty and blue, was the Earth. I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn’t feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.” We’re beginning to see here, perhaps, how the Overview Effect connects to the season of Lent and everything we’ve been talking about the last few weeks. I think when astronauts go up there and see the Earth, they instantly and instinctually recognize that they are in the presence of something Holy. This new perspective on the Earth pulls them beyond expectation and language into a numinous experience. (The Holy, to me, is not an idea, not a category, it’s an experience.) Now, as we have learned, being in the presence of the Holy—experiencing it—is not always everything our consumer spiritual culture likes to emphasize—it’s not all bliss, and blessings, and positive vibes. Sometimes, the Holy will knock you down! It’ll take you out! The experience of tremendous awe in the presence of that which is bigger than me is sometimes even called “the fear of God!” In 2021, William Shatner—who everybody knows as Captain Kirk from Star Trek—at 90-years old finally went to space—for real—thanks to Jeff Bezos of Amazon fame, aboard his Blue Origin rocket. This was a huge publicity stunt, of course. Bezos (or more likely his publicity team) recognized that we’re way more interested in Shatner going to space than any billionaire. And I’m sure they were dreaming of what Captain Kirk would say when he got back to Earth. Wow! What an experience! Best experience of my life! Let’s all boldly go to space aboard Blue Origin rockets! But that’s not what they got. Instead, on his space flight, Shatner experienced what he described as both “the most profound experience I can imagine” and “the strongest feelings of grief” of his life. He was filled with “overwhelming sadness.” He told NPR, “I was crying. I didn't know what I was crying about. I had to go off some place and sit down and think, what's the matter with me? And I realized I was in grief.” He wrote in his memoir, “My trip to space was supposed to be a celebration; instead, it felt like a funeral.” Now, we’re beginning to see how the Overview Effect connects us to Jesus’ Lenten teachings about dying to the self, about losing your life to save your life. What is so uncomfortable about big shifts in perspective like the Overview Effect is that the knowledge that we receive is usually bigger—sometimes far bigger—than the container—bigger than me. And so what happens when I realize that I am too small a container for the next stage of my own development? What happens when God speaks a knowledge to me that cracks me open from the inside? Something has got to be let go of. Something has to get out of the way. Something I’m very attached to has to die, so that something bigger can be born from it. Space philosopher Frank White, who coined the term “the Overview Effect,” tells us that enough people have been up and reported this experience that we can begin to get a sense of the initial pattern. It may very well start off feeling like a death or a trauma, but over time we get to a resurrection shift in consciousness—astronauts stop identifying with one small part of the globe, one side of politics, one small set of beliefs. They begin to see themselves—and all of humanity—as part of a much larger whole. This holistic perspective fosters a profound sense of unity, compassion, and responsibility for our planet and each other. The experience of that which is bigger than me is not an experience designed by God to keep us small; it’s designed to help us grow. You and I are probably not going to make it to space anytime soon. But part of the goal of Lent is to catch a glimpse—some firsthand experience—of a greater perspective, a holy perspective. This isn’t always easy to achieve. Lacking rocket boosters to take us to heaven we sometimes must travel in the other direction—unwinding ourselves down into the spiritual underworld through the prayer and fasting; humility and denying ourselves the comforts of the ego-driven perspectives that are our common companions at other times of the year. Whether we’re looking down at the Earth or humbling ourselves upon the Earth, the goal is the same—the realization that we are not entirely what we think we are. And when we let go of our attachment to the smaller thing we think we are, we enable ourselves to connect to the greater thing that God is helping us to become. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed