|

Well, we’ve got a real soap opera on our hands this morning, don’t we? You might not think that Holy Scripture should be this trashy, but here it is: Two women share the bed of the same man. Sarah is Abraham’s wife. Hagar is Sarah’s slave who Sarah gave to Abraham as a surrogate to bear children for Sarah because she thinks she’s too old to conceive a child herself. When Hagar gives birth, the children will belong to Sarah and Abraham, not to Hagar.

When Hagar conceives a child, Sarah begins to feel like Hagar is looking down on her. Maybe this was true or maybe it was just Sarah’s jealousy. We don’t know exactly what Sarah does in retaliation, but it’s bad enough that Hagar runs away into the wilderness before eventually returning to Sarah. (This basically becomes the plot of the dystopian novels and TV show, The Handmaid’s Tale.) In time, Sarah does conceive and give birth to a child (Isaac), and it doesn’t diffuse the tension in the household at all. Now that Sarah doesn’t need Hagar and her son, Ishmael, anymore, she wants them out: Abraham, abandon that woman and that boy in the wilderness (where they’ll likely die of dehydration and exposure) and let’s be done with them. This is hardly an edifying story, right? Sarah and Abraham don’t look too good here. They own a slave, she’s ordered into Abraham’s bed without even the possibility of her consent, she’s treated harshly and made miserable, and in the end she and her child are abandoned in the wilderness, thrown out, thrown away. One skin of water and a little bit of bread—Abraham was not poor, he could have given her more, but what he gave her was just enough to assuage his own guilt, right? It was not actually intended to make a big difference to Hagar and Ismael’s suffering or their ultimate fate. Now God enters into this mess in two places. And that’s what I’ve been trying to make sense of this past week. First, Abraham at least has the decency to feel guilty about abandoning the mother of his child and his son to the elements where they will likely die an awful death. So, he prays about it. And God, who had previously told Hagar (when she ran away to the wilderness) to go home again, this time approves of the plan. And God says, don’t worry about it, I’ll take care of them. You would hope that if one of us conceived a totally immoral plan to benefit ourselves at the expense of someone else and her child, and that if we prayed to God to ask whether we should go forward with this evil scheme, that God would say, No, of course you can’t do that and you ought to know better. Nobody’s gonna let you get away with treating people like that—least of all me. I don’t approve! And if your neighbor told you that they had conceived some sort of wicked ends, but that it was OK because they’d prayed about it and God said, “Yeah, sure, go for it,” you wouldn’t believe them a bit, would you? God would never approve a plan like that! But here we are. Instead of sitting in detached judgment over this soap opera as the ultimate moral authority, God has gotten Godself tangled up right in the middle of all this human drama. That’s troubling, but fascinating to me. Then God gets involved again as promised. Now, it’s strange because there’s nothing in this story that would have prevented God from acting like Hagar and Ismael’s fairy godmother, right? God could have turned the stones to bread, God could have made water spring up every few feet, God could sent angels to shade their heads, God could have turned a lizard into a camel and let them ride through the wilderness in style, but God doesn’t do any of that. God waits. God waits until the water and the bread are gone. God waits until their strength is sapped by the sun. God waits until Hagar has lost all hope, until she has dropped the young Ismael under a bush and walked as far away as a bow shot—close enough that she can still see him there, but far enough that doesn’t have to see him suffer and die. And in this final moment of suffering and despair, God finally acts. God sends Hagar back across the distance to Ishmael and there her eyes are opened, and she sees the well of life-saving water there where she had not noticed it before. What does it all mean? When I was growing up in Warwick, RI, I used to take the train up into Boston some weekends and hang out with my summer camp girlfriend up in the city. And the coolest place to hang out in Boston in the early and mid-90s was Cambridge Square. It wasn’t too gentrified. It was still pretty grungy, eclectic, weird. It hadn’t been taken over by all the chains and corporate brands yet. And right in the heart of Cambridge Square, right behind the entrance to the T was this small, brick, almost like an amphitheater. It was like a round little public space where you could just hang out. And back then it was the place where all the grungy teens hung out. Nobody else went in there except for the kids with the ripped clothes and the tongue rings. So, of course, I wanted to hang out there with them. But I didn’t quite fit in. They were a rowdy bunch. They were intense, certainly. And they had a bad reputation. The conception of them was that they were a bunch of drug-addicted, juvenile delinquent runaways and that they were nothing but trouble. But even though I was just hanging out at the absolute margins of that scene, that didn’t seem to be the whole story to me. I started at Boston University in 96 and at that point I felt confident enough to talk to some of these kids. And I discovered that “runaway” was not really an accurate term. A lot of these kids were abandoned, kicked out of the house, or on the run from serious abuse and neglect. A lot of them were LGBTQ teens who had been kicked out of the house or who had been subjected to such abuse that they had to run. Coming from a really healthy and supportive home this was really astonishing to me. I talked to one girl who told me that her mom had told her that she had prayed about it and that God had told her to throw her daughter out of the house as a punishment for her lesbian lifestyle. And I was like, This is awful, someone should make your mom live up to her obligation to you, someone should make her do the right thing! And this girl looked at me like I was crazy and just said, “Well, it’s better for me out here than it ever was for me in there. And it sucks. This is hard. But it’s worth it.” Meeting this girl really shook me spiritually. I prayed to God about it because I was angry with God and eventually slowly I got a surprising answer from God. God said, “No one can make her mother do the right thing. Not even me. And I had to get her out of that house somehow.” I left Boston was I graduated in 2000 and I didn’t come back until a decade late when I was working as a minister at a church two subway stops away from Cambridge Square. So, I went back to check on that scene, to see if those kids were still there. There little park was still there but now it was full of strolling tourists, and Harvard students studying, and business people eating lunch in the sun. Where had all the kids gone? I mentioned it to someone in my church and she told me that those kids were all living in a special shelter in a church a few blocks from the square for LGBTQ kids who had been kicked out of their homes. While the rest of the world had kept those kids at an arm’s length, trying not to see their suffering, God had been working quietly behind the scenes, providing a refuge for them. Just like Hagar, these young people had experienced abandonment, rejection, and suffering. They were cast out into a wilderness of uncertainty and despair, left to fend for themselves. But just as God saw Hagar in her distress, God saw these young souls in their pain and had been working to provide them with a place of shelter and support. God's response to Hagar's cry in the wilderness was not immediate. God's timing may not always align with our own. We may question why God allows suffering to persist, why God doesn't step in sooner to alleviate our pain. But the story of Hagar reminds us that even in the depths of our despair, God is present and working, preparing to bring forth blessings and transformation. God's involvement in the messiness of human drama is not a sign of divine approval for the wrongdoing or the mistreatment of others. Instead, it reveals a God who enters into our brokenness, who meets us in our suffering, and who ultimately seeks to bring about healing and restoration. The story of Hagar and Ishmael also challenges us to examine our own actions and attitudes towards those who have been cast aside by society. It prompts us to question whether we are truly living out the love and compassion of Christ, especially towards those who are marginalized and rejected. The story of Hagar and Ishmael reminds us that God's love and care extend to all, especially those who have been abandoned and marginalized. God sees our suffering, even in the midst of the messiness of life, and works quietly to bring about transformation and redemption. Let us strive to emulate God's love and compassion in our interactions with others, seeking to create a world where no one is left in the wilderness of despair but is instead embraced and uplifted by the grace of God.

0 Comments

Elaine, Jordan, and Nadine (and Lilly from afar),

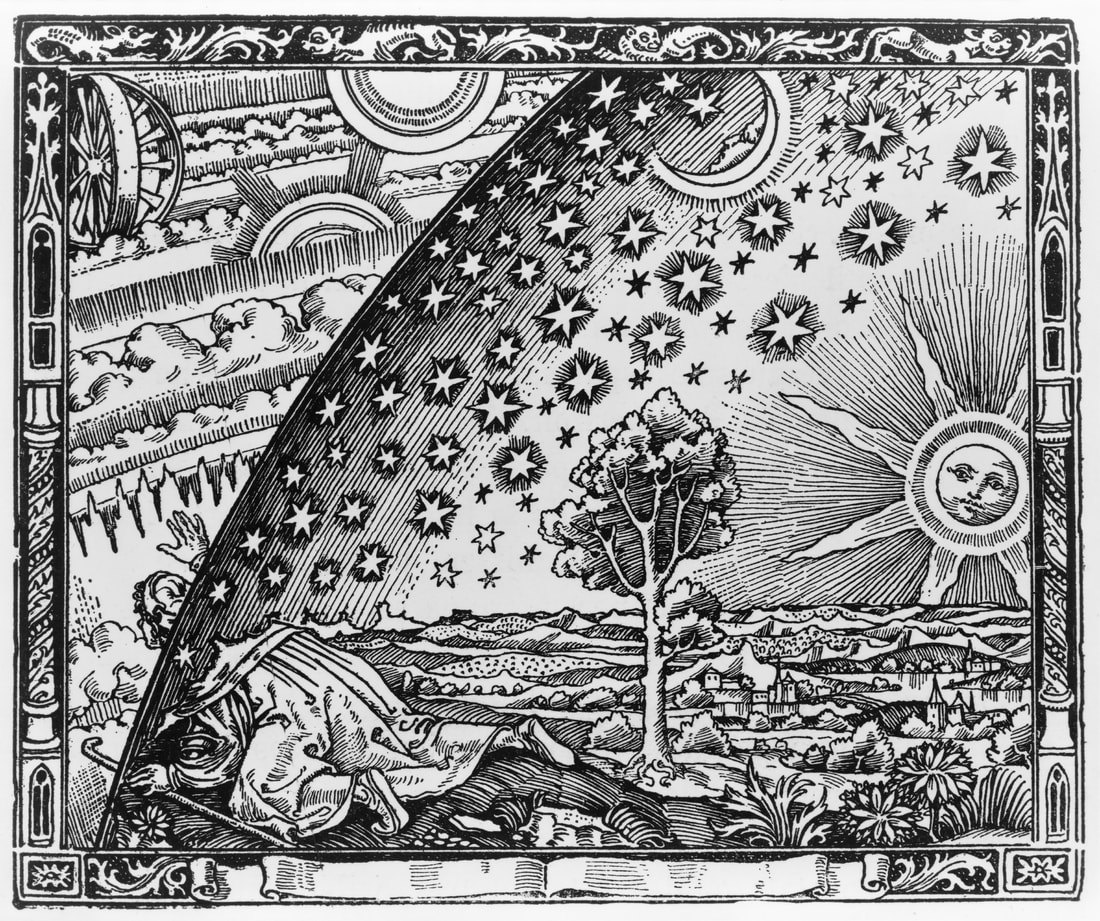

In our scripture reading this morning, Abram is called by God to leave his country, his kindred, and his father's house, and to venture into an unknown land. It’s a leap of faith, a journey into the unfamiliar. Maybe you can identify somewhat with how Abram must have felt—some combination of excitement and fear. Graduates, like Abram, you are now standing on the threshold of a new beginning. You have completed one stage of your journey, and before you lies a vast expanse of possibility. Just as Abram left his comfort zone, you too are stepping out of the familiar and embracing the unknown. The future may seem daunting, but remember that God is with you every step of the way. Now, as Abram journeyed through the land of Canaan, he paused at significant locations and built altars to God. These altars were physical reminders of his encounters and his relationship with God, symbols of worship and devotion. They marked sacred moments in his life and represented his commitment to God's plan. When you were born, your parents brought you into church (I think this church for all of you, right?) and we baptized you. You were too small to build altars for yourselves, so we built this first one for you. Not a physical structure, of course, but a spiritual marker that we prayed would stand out on the horizon of your identity and always remind you of God’s love for you, God’s acceptance of you, God’s presence in your life. When you were confirmed, we asked you to begin to participate in this spiritual altar-raising, as we guided you through the process of becoming members of the church. So, seniors, this is my simple charge to you this morning. As you transition from high school to the next phase of your lives, do not forget to continue to build altars to God. Again, not literal structures but spiritual markers—do not let this senior recognition be the final marker of your spiritual lives. Continue to journey with God and build altars of worship, build altars of spiritual growth, build altars of gratitude and of service to others, and build altars of love. Let the life ahead of you be a life filled with the Spirit and a life in which you remember to mark God’s presence in your journey. A literal reading of the creation story doesn’t really work for me. If you prefer to read this or any other part of your Bible literally, I won’t try to talk you out of it. I will always try to remind you that there are other faithful ways of reading and interpreting holy scripture. It’s OK to read your Bible literally, that is one option. But it’s not OK to try to make everybody else read the Bible literally, or to proclaim that a literal reading of the Bible is the only legitimate way of reading the Bible, or for that matter to claim that reading the Bible literally is not itself quite an impressive interpretive feat—trying to ignore the fact that a literal reading of the Bible requires just as many (if not more) sermons, and books, and explanations to fully understand it as the more open, or spiritual, or poetic readings of the Bible do.

Also, the fact of the matter is that no one reads their Bible entirely literally or entirely metaphorically. Everyone reads it both ways, the issue is which parts do you read which way. In a Boston-area town in Massachusetts there’s a great story told by the local clergy group. A Baptist minister in town was well-known for calling all the local phone numbers in his area, and whoever picked up the phone he would introduce himself and invite them to come to church. So, going through all the local numbers like this, he eventually called the priest at the town’s Catholic church. Being a good evangelical Baptist, the minister decided to evangelize his Catholic colleague a little, and he advised him to start reading his Bible literally. “Oh, I do!” said the priest. “You do?” “Sure, I do. Like when Jesus said at the last supper, ‘this is my body, this is my blood,’ I take that literally.” Now, Baptists, of course, unlike Catholics, believe that communion is just a symbolical observance—no real body and no real blood involved. And so the Baptist minister said, “Well, Father it’s been nice talking to you,” and hung up the phone. Nobody reads their Bible just one way. It’s all a mix. The phenomenon of the exclusively literal reading of scripture is really a modern phenomenon. You could be forgiven for thinking that way back when everybody read their Bible literally and then we let faith slip and we started to read scripture metaphorically just so we could get rid of the parts we don’t like or something like that. But it was always a mix until we get to modernity. And in modernity our culture has come to believe that the only truth, or the supreme truth, is the literal truth. We want to know what happened. Just the facts, please. Don’t tell me what it means, OK? Meaning isn’t truth. Meaning is subjective. Meaning is an illusion. Meaning is nothing more than a way of constructing oppressive narratives that benefit the powerful and the privileged. The universe, everything around us, the light, the water, the sky, the sun and the moon and the stars, life itself, human existence—there’s no magic there. No spirit. No meaning. If you want the truth of any of these things, you need to get a scalpel and a microscope out. And if you break the universe, and even human beings down to their smallest constituent parts, they’re all just a sort of chaos of dead atoms (which are mostly just empty space) bouncing around—nothing more. And that is the literal truth in modernity. There’s a new theory in philosophy and science right now that’s getting a lot of attention that argues it is statistically likely that we’re not even living in a “real world” at all. Instead, we’re all living in a simulation in somebody else’s supercomputer. And all we really are in that case is math. Dead numbers being crunched in the bowels of a computer. The problem with a literalistic reading of scripture is that it basically assents to modernity’s worldview. It says that the only truth that can stand up to modernity and nihilism is literal truth. Meaning won’t cut it. Mystery won’t cut it. Poetry and spirituality won’t get the job done… But demanding a literal reading of the Bible limits the spiritual imagination. And it is only a resurgence of spiritual imagination that can save us from the dead, spiritless, meaningless, simulated (literally unreal) universe of modernity’s materialism and physicalism. So, no, I don’t read Genesis literally, but that doesn’t mean I don’t read it faithfully. What’s that old saying? “We take our Bibles seriously, not literally.” Here’s something neat to know about the Genesis creation myth. The original community who told and wrote this myth down didn’t think that they were telling a literal, scientific, nuts-and-bolts story. It was for them an act of spiritual imagination. There is an older creation myth, the Babylonian Enuma Elish, which is strikingly similar to the Genesis creation myth. There’s not time to go into all the similarities between the two, and what really matters is the big difference. In the Enuma Elish a pantheon of related gods are all flighting and vying for power. Marduk, the sun god, triumphantly cuts his grandmother, the sea goddess Tiamat in half. Half her body becomes the earth and the other half becomes the sky. It is a blood-soaked, dominating, almost warmongering understanding of how the universe works. And the ancient Israelites had first-hand, tragic experience of the Babylonian empire’s violence, their drive to dominate, and their warmongering. So, when it came time for the ancient Israelites to tell the story of the beginning of everything, they were not lamely attempting to produce a sort of pseudo-scientific account. They were producing a cultural commentary, perhaps an act of political and spiritual resistance to empire, and a theological improvement on the Babylonian story. God didn’t kill the dark chaotic waters, instead God’s spirit hovered or swept over them. And instead of a blood-soaked, hypermasculine, dominating creation energy, we have a story of a God who forms the universe with restraint, with nurture, with care, with blessings, with rest, and with this refrain throughout, “And God saw that it was good.” It was good. It was good. It was good. That is what our ancient spiritual ancestors wanted us to know. That is what they wanted us to carry in our hearts and in our imaginations, “It is good. It is good. It is good.” It is good to be alive! It is good to be a part of this spirit-filled universe. Yes, that beauty you see is real. Yes, that meaning you feel in life is real. It was there in the beginning. And I hope we don’t lose the ability to see it, to feel it. But that will depend on our ability to nurture in ourselves and in our culture a spiritual imagination that doesn’t deny the facts, but that—I don’t know?—hovers over them, sweeps over them and fills them with life again. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed