|

“If any wish to follow me, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it.” This is one of the quintessential teachings of Lent and—although it makes us uncomfortable—it’s one of the quintessential teachings of Jesus—period—one we must come to terms to with.

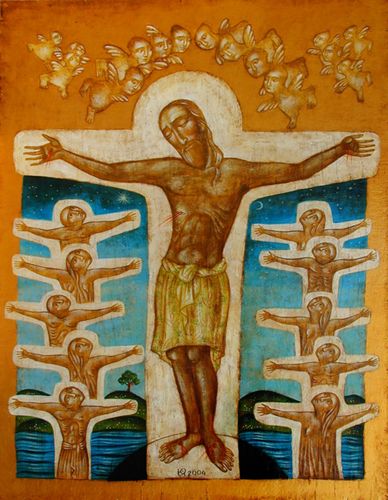

What does it mean to deny myself? What benefit could it possibly have for me or for anyone else? Is this just some sort of weird spiritual masochism? Or some insidious attempt by our religious overlords to undermine our feelings of self-worth in order to manipulate and control us? I mean, wasn’t Jesus all about love? Doesn’t Jesus want me to love myself? How can denying myself—negging myself—be compatible with loving myself? Let’s be real. We can all think of a narcissist or two who this teaching would be perfect for, but the rest of us? Come on! We’re not a bunch of oblivious egomaniacs here who don’t know how to practice any kind of restraint. That’s not us. We care about other people. We care about people who have less than us. We care about justice and fairness and equity. But we also understand that in order to make a difference in the world, I need to put myself out there. I need to assert myself. I need to fight for myself and to understand my value. And that’s hard work, isn’t it? So, after I’ve done that all week, I need to practice some good selfcare. I might even need to treat myself every once in a while—I deserve it and I need it. To be a success, I need a healthy ego that is strong and ready to fight to be seen and heard, to do what is right, and to get what is deserved. How could denying myself possibly fit into a healthy and productive life? The trouble with this cultural worldview of ours is so, so tricky. It assumes—very incorrectly and sometimes disastrously—that I know at all times exactly what it is that I truly want, exactly what my purpose in life is, exactly what values as a human being are important to me at all times. Now if I were always perfectly aware of exactly what is right for myself, then there would be no problem, friends, with charging straight ahead. But the reality of life is that our consciousness, our ego, is limited. We get so caught up in our work and goals that we lose touch with who we truly are, with what we really want, with what we actually think is important. The most common way that people in our world lose themselves is not through practicing self-denial. It’s by charging straight ahead into life, into commitments, into responsibilities, into work, and (although it’s everything we think we want), we find ourselves overwhelmed by burnout, depression, anxiety. We start acting out—substance abuse, gambling, an affair—risking everything that we’ve worked so hard for, everything we keep telling ourselves we’ve ever really wanted. This is the problem with a strong ego. Your ego’s job is to go out there and kick butt, to get things done, to put its nose to the grindstone, to change the world! Your ego is often far less adept at actually knowing what it is that you want. It’s far less adept at turning inward and paying attention to what might be changing. It’s like a racehorse charging down the road, pulling the carriage of your life along, and suddenly you realize it's the wrong road or maybe that you’re headed towards a cliff! It’s not the horse’s fault. His job is to pull the carriage. Somebody else is supposed to be at the reigns. Who’s that? The ability to pull on those reigns, to say “WOAH,” to slow down, to take the lay of the land, perhaps even to turn the carriage around is an ability grounded totally in the strength of self-denial. “WOAH, boy! Woah!” If you’re charging towards a cliff, self-denial is a key component of self-preservation—of saving your life! Self-denial is not the goal itself. Self-denial is a way of slowing down, paying attention, and redirecting—it’s a way of discovering who you really are. And this is the promise of a season like Lent: If I reduce myself, if I deny myself, if I sacrifice, I will come out of it not weaker but stronger—with a stronger sense of identity and a clearer sense of vision. When I reduce myself or declutter myself, I come to a place from which I’m able to connect to that which is bigger than me—to God, or to my true self, my true values, my true desires. The question for Lent is not “How can I make myself miserable?” or “How can I really impress God by beating myself up?” it’s “Who am I really? What do I really believe? What am I becoming?” That’s the point. That’s why we pray and fast and meditate. That’s why we slow down. That’s what we’re reflecting on. That’s what we’re asking for. Now everything I’ve just said about an individual can also be true of an organization, or a church even. In fact, organizations can sustain a charge in the wrong direction far longer than any individual person can. It’s very hard for organizations to slow down, to reduce, to let things go, to deny themselves in order to rethink themselves. It’s easier to just keep going than to reorganize. But organizations are so much longer-lived than people that they have to reinvent themselves at lot—at least every generation, and nowadays, in this changing world, maybe something like every decade or so requires pulling over on the highway of the world and to really check in on our identity and our direction. If we don’t, then the organization could have a little bit of its own kind of midlife crisis—burnout, anxiety, disconnection. Immediately after the worship service this morning is our annual congregational meeting. And you will quickly see that there is lots of incredible good news for our congregation from 2023 and a lot to look forward to in 2024. We’re not in a transitional crisis as a church. But many of our key leaders are realizing that we do need to take some time to really reflect on our true mission and vision in order for us to build 21st century ministries that reflect our identity here in 2024 and our goals over the next five to ten years. We see this a deeply spiritual and Christian process—in a very real sense we see it as a taking up the cross, of sacrificing for Jesus’ sake and the for the sake of the Gospel—a sacrifice the end goal of which is not depletion, but rejuvenation, resurrection, right? When Jesus says take up your cross and follow me, he’s instructing us in a kind of self-sacrifice, yes, but one that leads beyond the cross into something bigger, into resurrection. As Christians this doesn’t need to be anxiety producing, in fact, if we’re going to be effective in a changing world, it should be and it will be a regular part of our practice of spiritual direction. When we deny ourselves and take up our crosses to follow Jesus’ way, we’re temporarily slowing down, reducing ourselves, sacrificing, in order to come to a larger vision of who we truly are, what we truly want and need, and who we are becoming. Without a consistent practice of self-denial or sacrifice in some form, we tend to charge ahead on whatever path we’re on, striving to reach the top of the mountain, heedless of whether it’s the right path, or even the right mountain, or maybe we actually prefer the ocean to the mountains! Sacrifice raises our unconscious struggles and desires to consciousness where they can be worked out and integrated into our self. Self-denial and cross-carrying is a process of reduction in order to give up our ego illusion of total control. Our egos, though they are very good at getting things done, are not in control of everything. They don’t know everything, so who put them in charge? When we slow down and sacrifice and reduce ourselves, we make room for God to enter in and we discover more deeply who we really are. Sacrifice is a statement of holistic value—I am not here in this world merely to succeed. I am here in this world to become who God made me to be. You can hate yourself and still be accounted by history as a successful person in this world for your accomplishments. But you can only become the person who God made you to be, if you love yourself completely. And that is why the path of self-denial and sacrifice, as the way to your greatest self, is Jesus’ way of love.

0 Comments

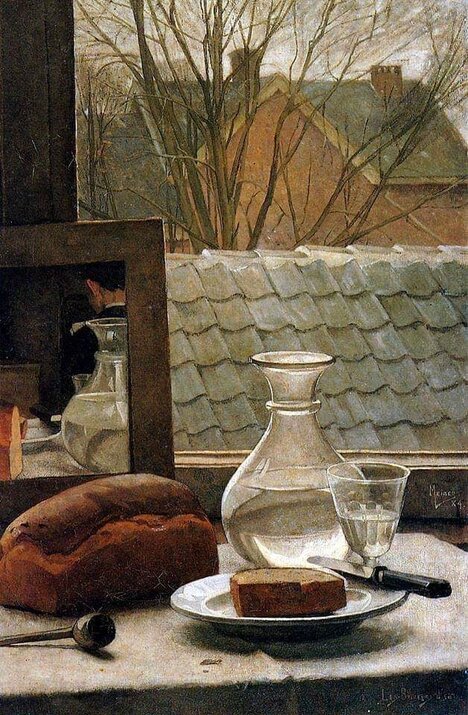

When the Spirit drove Jesus into the wilderness after his baptism, the Bible tells us that he fasted for forty days. Which is pretty impressive. Not bad, Jesus. But if you’ll allow a little flex here: today is my 49th day of fasting. I started on January 1. Please, don’t worry: unlike Jesus in the wilderness, I’m not eating nothing at all. On my fast, I eat every day. I just eat less. There’s an old tradition of Lenten fasting where you eat one vegan meal a day for Lent. Being a family man in an omnivorous household, I knew that going vegan would just be too much for everybody right now, so I decided to just try eating one meal a day.

Now, just to be clear right up front: I’m not being bananas about this, and I haven’t been able to eat just one meal a day for 49 days straight. I think I started with like three days of eating just one meal and decided to take it from there, paying close attention to my body and my health and the needs of the day. After three weeks, I worked myself up to a basic pattern of eating one meal a day for five days, and then eating regularly for two days. But, for example, this week I got a little cold, and I wanted plenty of energy for immune defense, so I added in an extra day of normal eating just to make sure I had all the food my body needed to be healthy. I want to be clear that I’m not being fanatical about this, which could be very unhealthy. Why am I doing it? Well, fasting is an important and traditional part of our religion, and I have almost no experience with it. I thought I should try it out and report back to you what I learned in Lent, which is the most traditional time for fasting and giving things up in Christian life. So, what have I learned? Lesson 1 is theological: Body and Spirit are United One of the first things I decided on this journey is that I wasn’t going to mess with any bad theologies about the human body. I was not going to fast to punish myself. I was not going to fast in a way that harmed my physical health or well-being. Causing yourself physical harm does not provide you with a spiritual benefit. Harming the body harms the spirit. The bad theology here is that body and spirit are somehow separate and that the body is bad, base, low and the spirit is pure, and that if you punish your body, your spirit will be freed from your instincts, urges, and animal desires. I thought that was the wrong perspective before I even started fasting. But if that’s wrong, what’s right? Well, fasting has brought me deeply in touch with my body, my physical needs, my appetites. I’m not usually a person who pays too much attention to that kinda stuff—needs, etc. Well, when you’re fasting, no matter what, you’re in touch with your physical being. And I discovered that the more I was in touch with my body, with what it was telling me, with how it was communicating to me, with what it wanted and didn’t want, the more I felt in touch with my self—my whole self—including my spirit. I’ve realized more deeply that the body and the spirit or soul are not separate things. They are intimately connected, bound together. This is one of the biggest misunderstandings throughout history of our Christian tradition. Christianity declares: God became flesh! And Jesus could’ve ditched his lousy body when he went off to heaven, but he didn’t, did he? He decided to hang onto it up there. In Christianity, even at the level of God in Heaven, matter and spirit, body and soul, through Christ have become reconciled and unified. Over the last 49 days I’ve learned that for me fasting is not an act of self-denial, but an act of holistic love. My theme this Lent in my preaching is “Bigger Than Me.” I’m not fasting to deny my self, I’m fasting to bring my self into loving balance with that which is bigger than me and beyond me. And this works not because the body is bad and if you beat it up your Spirit escapes it somehow. It works because when I intentionally and lovingly connect to my physical body, I come into deeper connection and balance with my self, with my spirit, and with God. Lesson Number 2 is practical: Fasting Is Consciousness Raising The USDA says that adults need between 1,600 and 3,000 calories per day depending on age, sex, weight, activity level, etc. The USDA also tracks that our food system in 2021 provided 3,864 calories per day for every person in the United States, including children. So, our food system is producing hundreds of calories more per day than any of us actually need. The companies that sell food are not content to let those calories go wasted, and they have strong profit incentives to entice us to eat more. New research is showing that highly processed foods which pack a lot of calories into easily digestible tasty little bites can be addictive and that we tend to eat more when we eat highly processed foods than when we eat whole foods. In an environment where there’s a feast all around us, which is being marketed to us everywhere we look, actually getting in touch with what our bodies need and want can be very powerful and balancing. As I mentioned before, I was eating fairly unconsciously. I wasn’t eating mindfully or intentionally. I wasn’t thinking, what does my body need today, what does it want? I was just kind of shoveling coal onto the fire. I wouldn’t say that I was eating compulsively, but I was eating unintentionally, without love, without care, without gratitude. And there were plenty of times that I was eating when I wasn’t hungry at all. I was eating because I was stressed or bored and the food dampened the discomfort or those feelings and enabled me not to have to think about what it was that I actually needed in that moment to be holistically healthy. So, by fasting, I’ve taken an activity that in my life (eating) that had become a sort of unconscious, unintentional act, and I’ve raised my level of mindfulness and made it conscious. Eating is so fundamentally important to our daily lives and health that anything that can help us to do it mindfully and intentionally is a good thing. Over the last 49 days I’ve learned so much about what my body needs and doesn’t need. And I’ve had to confront all those little instances of discomfort when I wanted to run to the snack cabinet and grab a bag of chips, and I’ve had to deal with them on their own terms instead of quieting them down with comforting, readily available calories. Lesson number 3 has been inspirational: As Anne Lamott once wrote, “It’s good to do uncomfortable things. It’s weight training for life.” I’ve discovered over the last 49 days that there’s a connection between being intentional and aware and being uncomfortable. It’s not just when you’re fasting or doing something hard, whenever you’re really paying attention, whenever you’re being purposeful, whenever you’re intentionally trying to grow, whenever we want to connect to that which is bigger than me, we’re going to be a little uncomfortable. So, it benefits us to occasionally or regularly engage in spiritual practices that challenge us and make us uncomfortable. Because it expands our capacity to be fully alive and engaged with the world. Fasting has slimmed me down, physically. But I feel spiritually bigger than I did before. So, to sum it all up: Fasting connects us to one of the most radical realities of Christianity—that body and spirit are united together. Fasting raises our consciousness: By eliminating all unintentional eating, we begin to listen to what our body is telling us about what it wants to eat and when it wants to eat. And we’re forced to confront anything else in our lives we were avoiding by eating yummy stuff. Fasting is good for us when done in healthy holistic moderation because it’s good for us to do uncomfortable things. Uncomfortable spiritual exercises increase our capacity to do uncomfortable things like raising our consciousness, living intentionally, discovering our purpose in life, paying attention, and growing. If you’ve decide to fast or give something up this Lent, I pray that it feels like an act of holistic love, that it connects you more deeply to your self and to God, and that inspires you to grow on your spiritual journey. My theme for this lent IN my preaching and worship planning (and just sort of what I'm thinking about) is “Bigger Than Me.”

And Lent is a perfect time to explore the smaller side of ourselves, or at least the less inflated side. Let's call it that, the less inflated side of our lives, right? Getting back to simplicity, remembering that we're not perfect, we're not God, we're not infallible. We are not the center of the universe. No matter how much our lives and our careers and our families and our social medias and all of our desires and wants may suggest it to us, we are not the center of the universe. And so Lent is a time to explore humility and self-denial and try to find a little bit more of a deflated size. Not too deflated, but just sort of the right size for a mortal human being to be. Because I would suggest to you that one of the greatest spiritual realizations that it is possible for a human being to have—a mountaintop moment, something that when you feel it, you will remember it for the rest of your days—is to find your proper size and to realize that there is something so much bigger than me surrounding you and within you. The imposition of ashes, which we all just did with one another, is a perfect example of a Lenten activity that we do together to remind ourselves of our smallness, to sort of deflate ourselves down to the proper spiritual size. The ashes remind us that we are dust: from dust we came, and to dust we shall return. Maybe you were thinking very highly of yourselves before you came in today and you were thinking, “Man, I really pulled it all off at work, and I got dinner on the table, got the kids fed, got 'em in here, I'm king of the world. I'm doing it all!” and then you remember: from ashes you came, to ashes you shall return. It's about finding your proper spiritual size. But then we also have to remember the ashes that we came from, the dust that we came from when God formed us from the dust of the ground in the Garden of Eden, God just didn't put us together like a sculpture and then leave us alone. God reached down into the ground where we were formed and breathed life into us, the very breath of God, Spirit. And so what are we? Are we just dust? No, we're dirt, clay from the ground, from the earth, and we're the Spirit of God mixed together in some mysterious, beautiful way. In a moment, we're going to have communion together. And communion is another opportunity for us to remember our proper side. The imposition of the ashes tonight reminds us that there is something bigger than me because I'm finding my proper size. I'm getting down to the right size, the humble size, the size that knows I'm not the center of the universe. And then part two, just as important, we come to this table, the table that is God's sustenance for us. God's food for us. The table that contains the body and the blood of Jesus Christ, where God calls us for communion to be with God intimately sitting and eating. And we eat God, take God into our bodies, so that God now is inside of us. It was the German philosopher, Feuerbach, a materialist, an atheist, who gave the saying which in English comes down to us from him as, “You are what you eat.” And we think of this a lot of times in terms of diet. Don't eat junk food. But he actually meant that the world is just material. And this big question of what does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be human? What am I? What am I? He said, no, no, no. It's just whatever you eat. You're just an animal. You're just a physical process consuming physical things. You are what you eat. There's no more mystery than that. If you eat beets, you're made of beets. If you eat pigs, you're made of pigs. There's no spirit, there's no soul. You are what you eat. But as Christians, we come to this table and we eat God! God is within! So the theme for this Lent is bigger than me, and it's a much needed medicine for people in our world to remember that we are not the center of the universe. And yet at the very same time, we remember that the ashes that we came from were infused with the very Spirit and breath of God. That is what I am. That is what you are. And we remember at the communion table that we take God into our body through God's own grace in a miracle of sacrament. Bigger than me means finding my right size. And from that place of self-denial, sacrifice, and humility (a little bit smaller probably than we were the week before) we begin to see our true greatness—that we are surrounded by God's Spirit and that the kingdom of God is within. Beloved, I think that what happened to Jesus on Mount Tabor is happening in some sense to all of us, not physically, of course, transfigured, but in a spiritual sense. We are, through our faith in Jesus Christ, being changed, being transformed, and in the process of transformation, we find ourselves to have so many questions, so many concerns along the way. So this is an "Ask Me Anything" opportunity. Anybody have a question they would like to ask Pastor Jeff? It will be answered on the spot and if I can't answer it on the spot, I'll put it in my pocket and I'll bring it back up some other time in a service. Does anybody want to go first? Jan, you want to go first? How unlike you, Jan.

Jan: I would like you to make some comparisons to the major religions of the world and what we believe, especially about love and equity. Okay. I'll mention a few. First of all, I think it's very important to know, well, we all know what we believe in terms of love and equity. I hope. Basically love your neighbor as you love yourself. That's the most important principle of the gospel. The whole of the law is contained within that we understand, and Jesus of course, was Jewish. He was commenting on the Jewish tradition. We could say that Jesus is a reformer, but we know for a fact that love your neighbor as yourself is not something that Jesus thought up as an original thinker. He received it from his Jewish tradition. And so Judaism and Christianity really stand shoulder to shoulder in this regard. We love our neighbors as we love ourselves, and Jews have this wonderful idea that we share in Christianity, but they have this word Tikun. And Tikun means to sort of be a repairer of the world—somebody who is a part of God's plan to redeem the world in some sense for us all, maybe in some ways to become people who love and change the world with God in partnership with God, which is an idea that we share very much. And another tradition I know fairly well is Buddhism. And so I'll just talk a little bit about Buddhism. One of the major tenets of Buddhism is compassion and to have compassion for everybody—every being—and understanding. And I think in compassion we begin to recognize that there is no difference between my neighbor and I and that in fact we're all we really have down here in the world besides God and the spiritual powers. We have one another. And to understand that the life another person is living is only a hair breadths away from my life and it could have been my life just under different circumstances (right?) is something that draws us closer together to those who are our neighbors, to those we might consider to be our enemies to those we think we could never understand how they think or how they live, but we can. And the way through it is compassion, which is a trait that I think also Jesus recommends to us over and over and over again. So those are three religions. I can't do 'em all. Jan, you get three and maybe we'll come back to some other ones, some other time. Craig: In the gospels we read about a person who asks, "What must I do to inherit eternal life?" Jesus responds, "Obey my commandments." Suppose some 20 years later the same person meets the Apostle Paul and asks the same question: "What must I do to inherit eternal life?" Paul's going to say believe in Jesus Christ, his death, and his resurrection. Totally different from what Jesus said! And Paul's going to point to Abraham, who lived before all this, and in reading Genesis it was said his belief in the Lord was accounted to him as righteousness. So, Pastor Jeff, what must we do to inherit eternal life? Oh, an easy one. Thank you, Craig! What must we do to inherit eternal life? Well, I think that Paul gives us good guidance, right? Because Paul directs us back to Jesus. And Paul says, Hey, my experience of this whole thing is you have to believe in that Jesus, that real spiritual power who can come down from heaven and nail you between the eyes, knock you down and change your life through the power of what was Paul's direct spiritual experience. Paul didn't live with Jesus. He didn't know Jesus in the flesh. He wasn't a disciple. He didn't walk with him. He never heard him preach one sermon. He never saw him do one single miracle. He was not there. He didn't sit at a table and eat with him, right? He was sort of maybe off on the periphery, persecuting some of the disciples at some point, but he did not know Jesus. His experience of Jesus is that resurrected, real, living spiritual power who will come down from heaven and nail you and take over your life in a way that changes everything. And we should believe the witness of Paul: God can do that to your life. And if you let God do that to your life, if you let God change you, that's one of the definitions of eternal life, of being saved, right? And we should be grateful that we have the gospels and we have the tradition of the disciples and the churches who also bring down to us Jesus's teachings. And so we should always listen to Jesus' commandments because what Jesus had to say is extremely important to our understanding of how it is that we ought to live as people who have been seized and transformed by the power of Christ. Not all of us are as lucky as Paul, okay? We don't necessarily have that supernatural experience of God reaching down, blinding us and just taking over our life. I mean, the Holy Spirit just took Paul over. It wasn't his intelligence, it wasn't his will, it wasn't his idea. He didn't say, you know what? I think I'll let the Holy Spirit took me over. That would be a wonderful thing (maybe!) to experience. But not all of us are so lucky. And so when we feel the movement of God in our life and it's not a total takeover, how are we going to live? Paul was lucky. He was completely taken over and he lived like a wild man on the edges of the world and he did his penance for the life he had lived before. But for the rest of us, how are we going to live? We're going to follow the commandments of Jesus. We're going to follow Jesus' commands. And then I would also say this idea of a righteousness being something that saves us. I also think that that's an important piece of the puzzle. The reason we are transformed by God is to increase our capacity for doing good in the world, right? That's why God transforms us. And there are all kinds of ways that this happens. Maybe God reaches down out of heaven and slaps you around and you are in that moment seized by the spirit and saved. That's an incredible experience. Or maybe you get taken out by a terrible illness and suffering and loss in your life and then you come through it, you work through it with God. And on the other side of that terrible suffering, which was no fair, you discover that your capacity for goodness and love and justice in this world is 10 times greater than it ever had been before. So it's important to pay attention to that idea of faith and righteousness because that increases our capacity to understand where it is that we are going, who it is that we are going to be. You can follow Jesus' commandments and they point you in the right direction. But there's also, in the idea of righteousness and faith, an expanded spiritual consciousness about what is my purpose in my role in a world that is suffering and needs me. So my answer is all three, and probably a little bit of other things as well. Miles: Something I think about in context of faith, which is a little bit new to me in my life is the concept of a chosen people, which is something that comes up in different religions. I'm curious how you think about that. Wonderful. So let's talk about the concept of the chosen people in our Christian context. We acknowledge through our history and through the Hebrew scriptures, which are a part of our Christian tradition as well, we adopted them in, incorporated them in through Jesus, that the Jewish people were God's chosen people that God had—this is our theological tradition—God had a special love for the chosen people, the Hebrew people who became the people of Israel. And God had a special plan for those people to be God's special people in some sense, maybe even God's priests on the earth. And then God said, oh, I have an even better idea now here comes Jesus, and Jesus is going to come through this tradition and he's going to come through this bloodline, these people and be a messiah, not just for those people, but for the whole world. So it's important to recognize that we affirm the Jewish people's claim, and I think we still do theologically, that they are a chosen people. At the same time, there are a lot of traditions that feel like they're the chosen people. And I think it's important when we think of ourselves as chosen people (And this idea has come even into our American culture quite a bit. The idea that the people coming into the new world were God's chosen people who were chosen for this land to take it over, which is maybe an unfortunate theological echo of what happened with the promised land—of taking it over from the people who were already here and turning it into God's productive land. We had this idea in our heads that we were the chosen people escaping from Europe and coming to this country). So it's important when we think of ourselves as chosen people to recognize that it has a shadow side. Being the chosen people is a wonderful thing! Man! To be chosen! It's incredible to feel God's finger on you, to feel God's eye, to feel that incredible expectation and to know that there is some great future for you and your bloodline and your people. Wow, amazing. Great. But there's a shadow to it. When that idea gets inflated in your mind, you inflate yourself to believe, well, I'm the only person that God cares about. I'm the chosen one. What I think matters most. What I feel matters most—my life and my land and my rights are what matter the most. And that is something that can happen when we feel like we are the chosen people. And I believe we are the chosen people, and I believe everybody else is the chosen people too, it just all happens in their own different way, from their own different perspective. What's important is that we remember we're all God's children, we're all God's children. And all of us were chosen to be God's children. So in the idea of being chosen, which is wonderful, incredible, amazing, live in it, feel it, know it, but don't go crazy with it. Remember that you're just a mortal. You're just a human being. You're imperfect. And God has chosen everyone around you too, and their perspectives are just as chosen and just important as yours. Oh, Bonnie Mohan. For those who don't know, Bonnie Mohan's, my wife. So, this is going to be real good. Bonnie: So, as your wife, I happen to know that there's a weirdo inside you that I think this congregation doesn't always get to see. And one of the weirdo elements about you is your interest in the paranormal—we went this weekend to a paranormal museum. So, I'm wondering how you see your interest in the paranormal alongside your beliefs in God. So Bonnie wants everyone to know that I'm a weirdo who's fascinated by the paranormal. And so she's asked me to comment on that. And let's talk about for a second (to just put it in a little bit of perspective) the Transfiguration, which we read about in our scripture reading this morning. Here's this incredible miraculous moment where Jesus is utterly transformed in front of three of the disciples. He's up there and he's talking with these two spirits, Moses and Elijah. They're there, they're speaking together, and God's voice comes down from heaven, Jesus becomes blazing white light—a miracle! If you were to go and experience something like this today, you would call it a miracle, you would call it supernatural, you would call it weird. It's incredible thing that's happening up there. I believe that these kinds of miracles, transfigurations and maybe some of the other weird stuff that happens in our lives (it doesn't have to necessarily be a UFO or a ghost, but those moments where you get stopped in your tracks and you say, wait a minute, something outside of my normal humdrum day-to-day, boring, materialist reality is trying to get my attention here. Maybe it's a coincidence. Maybe it's seeing something out of the corner of your eye, or maybe it's just like you all of a sudden are seized by a kind of spooky feeling in the dark and you feel like something is watching you, something is trying to get your attention—a dream you might have), I believe that these kinds of miracles and maybe some of these supernatural phenomenon, paranormal phenomenon are the inbreaking of God's meaning into our physical world. That's what happened at the Transfiguration, right? God's meaning became so concentrated in Jesus and his relationship to his tradition and to those disciples that the meaning had to come out in the physical world and the physical world couldn't contain it as dead matter any longer. It came alive, spiritually alive. And so that's my answer about why the paranormal, supernatural stories of miracles and saints interest me so much is I see it as one way that meaning God's meaning, God's purposes and intentions and Spirit break into our world in an actual physical way. And if you believe in miracles, you believe that that's something that can happen. Rita: Do you think physical God as man will walk on Earth again? Or more the miracle of a vision, for example? Do I think that God in human form will walk upon the world again? Walk in the world again in physical form? Wow. What a wonderful question. My instinct, my intuition here is to answer it like this. I believe that Jesus Christ came into the world in order to show us the reality that that which is human can be so much more than human because Jesus was fully and totally human and at the same time fully and totally God. Now I believe that that was unique, and I don't believe that that's what's happening for you or for me. And yet God was showing us something that we couldn't have possibly believed before. And we even now today, have trouble believing that which is human is a perfectly acceptable, wonderful, beautiful, possible container for everything that is good, holy, sacred, beautiful, and divine. The human can fully contain, be filled up with to overflowing with that which is God. Now we're mortal and we're imperfect and we're never going to be Jesus. And yet there is a way, I believe, through faith in Jesus and through the process of coming to know God more deeply and coming to know our own self more deeply, that God comes alive in us and we walk a little bit more with God's feet and our hands even more become God's hands in this world. Which isn't to say that we are gods, we're not, but we're not "just human." We're more. God made us to be more. And Jesus is that absolute confirmation. You can be more than "just human." You can be more through your faith in Jesus. God comes into the world, not just through Jesus's incarnation, but through the incarnation of each and every one of us in a smaller way. That's what the Church is. It's Jesus's body on Earth now that he's gone, and each and every one of us is a part of that. So God is on Earth through the Holy Spirit, through our miraculous incarnations, through our associations and relationships with one another as a church reaching out into the world. Great question. Thank you. Wonderful questions everybody. And we've got to stop, but we'll do this again sometime soon. And if you did have a question you didn't get to ask, email it to me or let me know and maybe I'll turn it into a sermon sometime. Thank you. Preaching on: Mark 1:29–39 We’re only in Mark, chapter one. Mark, chapter one. Jesus has hit the ground running. He has called his disciples, he has taught in the synagogue, he has cast out demons, he has cured the sick. He has already had to sneak off in the dark to get a little peace and to pray. And when his disciples find him, they tell him, “Everyone is searching for you.” Everyone is searching for you.

I wonder if that line is true in some larger sense than the disciples could have imagined. I wonder if everyone is searching for Jesus. I believe that everybody is searching—or at least hoping—for something. The condition of many people outside of the Church, or another religious tradition, is that they don’t necessarily know what it is exactly that they’re searching for. But they’re all searching for something that will satisfy some deep longing within them. And the condition of many people inside of the Church is that because the answer to the question has been provided to us all along (Jesus is the answer, of course) and we didn’t necessarily have to discover it for ourselves, many of us have not truly experienced the question that I believe Jesus is the answer to. And so we’re something like the people of the planet Magrathea in Douglas Adams’ novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. After waiting 7.5 million years for their supercomputer, Deep Thought, to produce the ultimate answer to the question of life, the universe, and everything, the computer spits out the response “42.” 42? After expressing dismay that they’ve waited 7.5 million years for the number 42, Deep Thought explains to the Magratheans that this is indeed the answer, and that the problem is simply that they don’t truly understand the question yet. And so the possibilities in my mind of these two groups of people getting together are limitless. On the one hand, the unchurched seekers who are walking the streets every day trying to find their way and longing for a sign to point them in the right direction. On the other hand, the churched seekers who have long held and studied the map of the city and who long to experience the profound miracle of being lost and then found. If we mix the questions and the answers we’re going to get a chemical reaction that produces energy, light, heat. In other words, transformation. Soren Kierkegaard, the great 19th century Danish philosopher, theologian, and existentialist argued that truly hearing and responding to the Christian message demands a personal transformation, a leap of faith that sets one apart from the crowd. This is a challenge in a Christian environment or culture, where Christianity is often taken for granted and not lived out in the radical manner that Kierkegaard believed the New Testament portrays. In Kierkegaard's view, the very familiarity of Christianity paradoxically makes it more difficult for individuals to genuinely engage with and understand the Christian message. He believed that in spaces where everyone is considered a Christian by default, the radical and demanding nature of true Christian faith is often watered down or ignored. Kierkegaard has convinced me that if the story of how we came to be Christians and the story of how we got to the answer of Jesus is simply that we were raised in a Christian land or in a Christian church, instead of a story about a radical encounter with a God who heals, exorcises, and saves, with a God who has transformed your life, then our story will always lack the existential depth and commitment to be able to convince anyone (including very often ourselves) that our answer matters. If I’m right about this, then the unchurched should be able to find Jesus inside this sanctuary. But only if those who are churched and holding the answer have first found Jesus outside the sanctuary—Jesus not in the form of an answer, but Jesus in the form of “the least of these,” Jesus in the form of human beings living, and enjoying, and suffering a human life. Jesus can only be convincingly offered as the answer if those who hold that answer have truly experienced the question for themselves and the transformation that comes when the key is fitted to the lock and the door that blocked your way is finally opened wide. Do you believe that Jesus is the answer? If so, what question or what experience or what deep longing in your life has Jesus provided the answer to? It’s the answer to the second question that makes your answer to the first question matter. No one is going to care that Jesus is our answer unless we back that answer up with a story, with an experience, with some measure of devotion and love scratched out of the hardships of this life. That’s why addicts in recovery are some of the best evangelists. Because they’ve lived and suffered through some of the worst experiences of what it’s like to try to satisfy the terrifying longing at the center of life with stuff (like drugs and alcohol) instead of with (what the 12-steps call) your “higher power.” To me, Jesus the answer must always be secondary to Jesus the question. And that means, as a church, we should orient ourselves first and foremost toward those who question, rather than orienting ourselves first and foremost to those who have the answer. We should prioritize those who seek, rather than those who have found. We should prioritize our own doubts, our own questions and experiences, our own failings and longings. We should tell these stories to one another. We should tell these stories in church. Because nobody wants an answer from somebody who doesn’t seem to understand the question. Everybody is searching for something. And Jesus is an answer available to every person that can bring profound meaning, comfort, healing, challenge, love, and purpose to our lives. Whether we are unchurched and longing for an answer or churched and longing to experience our answer actually transforming our lives, we are all searching for Jesus. And we will find Jesus most fully when we come to embrace the true meaning of what it means to be searching for Jesus—the simultaneous experience of being both lost and found. This is the point of convergence where transformation can happen for all of us, where Jesus ceases to be an answer and becomes what he truly is—the experience of everything that truly matters and the grace and love that surround us all. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed