|

We don't often think of New York City as being a place of spiritual pilgrimages. But here's one that happens every year. When I was living on the Upper West Side, I got to experience it one morning in late June on the summer solstice to be exact. I got out of bed long before the sun rose and walked over to the cathedral of St. John the Divine, one of the largest church buildings in the world. It was sometime before sunrise, before 4:30 AM when I arrived. But the street and the stairway up to those giant doors of that church were bustling in the dark with the quiet pilgrims, thousands of us filing into the dark interior of that cathedral. It's never really dark outside in New York City, you've probably noticed if you've ever lived there or walked through the city at night, not truly dark, but inside that enormous cave of that church, it was truly dark.

And there were ushers there who were helping us through the narrow pathways between all of the seats in the dark. And they had these tiny little flashlights, but they were using them sparingly. There were no lights on in the whole place. And only if somebody was really struggling did they flash the lights for you so that you could see where you were going, only when necessary. They were there to guide the people, but they were also there to protect the darkness. Once we were settled into that holy darkness, the organ began to play a concert of low rumbling notes that filled the entire chamber of that space. And as the music played, slowly (as our eyes fully adjusted to the total darkness) we began to see a glow. It was coming through the cathedral's 40-foot-wide, east-facing rose window. The sun was rising, and it was not just any sunrise. It was the sunrise of the longest day of the year. 10,000 individual pieces of glass began to glow, and then sparkle, and then blossom with color as the organ swelled and crescendoed. It's one of New York City's great mystical traditions, a ritual that reaches deep into our spiritual history and celebrates the bright light of summer and everything that the coming of the light represents to us symbolically and religiously. But the key player in this drama, the force that keeps the ritual alive and grounds it, the preset cue that welcomes the worshiper is the darkness. Now, if the concert started at 10:30 in the morning, I'm sure that, you know, maybe even hundreds of people would attend. But at 4:30 in the morning, thousands attend because you cannot experience the beauty of a sunrise except from the position of darkness. Let me give you another example. It also happened in a church. Many years ago, my wife Bonnie Mohan, and I had been dating something around a month. She was living in the Bronx, not far from Fordham University, where she went to school. She had recently graduated, and one night she was just giving me a tour around campus to show me all her old haunts. It was late at night because probably we had been out at a bar or something like that. The point is that we get up to the chapel for the school, which is a great big Catholic chapel church building. And of course, it's like two o'clock in the morning. So the place is completely shut down. It's completely dark. But for some reason, Bonnie, who I can guarantee you never darkened the door of this chapel one time her entire four years of college, reached out to the door and pulled, and someone had forgot to lock the church. And so we went inside together and it was absolutely dark in there, but for some reason we filed in and sat somewhere in the middle of the church and just stared up into darkness. And we sat there next to each other in silence, holding hands. And I'd say we sat there at, you know, something like two o'clock in the morning for about 30 minutes in total silence. And in that darkness, in that space, a connection happened between us, a deepening connection that could not have happened, I really believe, if the lights had been on, because if the lights had been on, we've been looking all around and people would've been able to see us and know that we weren't supposed to be in there. The darkness kept us safe, and it kept us together, and it let us reflect. And as we kind of came out of that meditation together, I turned to Bonnie. And for the very first time in our relationship, I said, “I love you.” And that I love you happened in the dark. And I believe it only could have happened in the dark. The dark let it be revealed. The reason I'm telling you stories about the dark is because today is the first Sunday of the Christian year, the first Sunday of Advent, and Advent is the season before Christmas. Christmas, as you all know, is the season of the sunrise, and that means that advent must be the dark before the sunrise happens. But that's a tough sell nowadays. In holiday time, I really hate to sound like that old curmudgeon, but I was driving around right after Halloween, I think it was the week after Halloween, and people already had their Christmas lights up and their Christmas decorations up. And I'm like, goodness gracious. Some people still have like skeletons on their lawn and other people have Christmas lights up. It's a bit of a juxtaposition. And there's nothing wrong with that! There's nothing wrong with the beautiful sparkle lights except that, you know, this Christmas creep from late December and early January into early December and late November and now early November, it prevents us from giving Advent and from giving darkness it's due. You know, we like the idea of hopping from one high point to another high point, to another high point without ever stopping or pausing to catch our breath in between. That is our culture. Go, go, go, go, go, go, go. Focus on the positive. Stay positive. Hashtag blessed all the time, Instagram, social media, everything's beautiful, everything's perfect. Everybody is living their best life now. And now is always, and everything is always bright and shiny and perfect. Market it baby! And it's all baloney and we all know it. You can't live like that. And any culture that would ask us to live like that all the time, not acknowledging the fact that the bright light requires sometimes a little bit of rest, it's just asking us to behave in a way that's manic. Darkness brings balance. We cannot live in the dark forever. But when we resist venturing into the darkness of our traditions in our spiritual lives, we alienate most of the people we think we're trying to protect when we keep the bright lights on all the time: the people who are living through the darker times of life. Now, as a minister, I know many, many people who have had something happen at Christmas, for instance, the loss of a loved one on or around the Christmas season. And they come to loathe holidays that they once loved. Why? Why should that have to happen? Because the bright lights of Christmas and the holiday cheer don't make any room for the grief that they are going to always have to carry at that time of the year. Because it comes around annually. We need to make a little bit more room for darkness in our lives. I've been beating around the bush a little bit here. But you know, this is true of all of us to a certain extent. We're a little bit afraid of the dark because you know, when the lights are out, you can't see what's coming physically or spiritually. When the lights are on, you can see what's coming. You can react, you can respond. But when it's dark, you don't exactly know what's coming for you. And that makes darkness frightening for many of us. And it doesn't help when Jesus says on the first Sunday of Advent that when he arrives in our lives, he is going to come like a thief in the night. Well, that doesn't sound very appealing. Why would Jesus want to do that? You would think that Jesus wouldn't want to associate himself with such an image, a thief in the night. Can you imagine how Jesus' PR department and his branding consultants must have been pulling their hair out when he let that one fly? A thief in the night? Come on. When a thief came in the night in Jesus’ day, the thief didn't announce themselves. They snuck in while you were asleep and while you weren't paying attention. And in those days, people didn't have like flat screen TVs hanging on the wall and all that kind of stuff. You didn't have a whole lot of stuff. Maybe if there was something to steal in your house, it was hidden away somewhere like inside a couch cushion or something like that, your savings, a few coins, a little bit of silver. And so you would wake up in the morning and you might not even know that your treasure had been taken away because someone had snuck in and gotten it away from you. Advent is a season that asks us to pay attention, and it asks us to take our treasures out of their secreted, hiding places to check on them. What are the treasures that you have in your life? What are the gifts you hold in the darkness? You go and you pull them out of their hiding places, and you hold them in your hands and you think about them, meditate on them, tell them that you love them. Maybe stay up all night, waiting, watching, praying. You keep your eyes on the window for a little bit of light that's going to come in. It can happen when you least expect it. Jesus can show up. Your treasures may be needed. Keep them close. Stay awake. Don’t lose heart. So this advent, let's not be afraid of the dark. Let's use the dark to watch for the coming of the light.

0 Comments

Preaching on: Deuteronomy 26:1-11 In August of 2013 I went on a vacation that changed my life. It was a road trip out West with my then girlfriend now wife, Bonnie, and Bonnie’s mother, and Bonnie’s sister, and Maura, Catherine, and Niamh, Bonnie’s cousins. I had never spent any significant time with any of Bonnie’s relatives, and now I was about to spend 10 days in a minivan with her and five of her closest female relatives. The joke from the Mohan women was that if this vacation didn’t scare me off, nothing would. I mean they laughed when they said it, so maybe it was a joke, but I knew this trip was also a test of sorts, and I was a little nervous. And so were they, and so was Bonnie. What would we discover about one another?

The road trip started in Yosemite National Park, and we did a lot of hiking. On the third day Bonnie and I hiked from the valley floor up to Glacier Point. We thought we’d have enough time and energy to hike up and back down, but by the time we got up to the point, we knew it was probably going to be dark by the time we got back to camp, and we were tired and hungry. You can drive up to Glacier Point so we asked some normal looking people who looked like they might have room in their SUVs for us if they’d mind if we hitched a ride down with them, and they all practically fell over themselves trying to get away from us as fast as possible. So, we call down to Bonnie’s family to drive up (which was a long ride) and get us. But while we were on the phone, some German tourists pulled over for us, with just enough room in their little rental car, and they said they heard we needed a ride, and they offered us a ride down the mountain. They were three wonderful guys and I really appreciated the ride. They were even going out of their way a little bit to get us back to our camp. When we got back I insisted that our German heroes get out for a bit and join us. I appreciated their kindness and I wanted to offer them something, but it was our last day of camping, and I wasn’t sure that we had much, I was also really tired. And this is the moment that I’ll never forget from that trip. Bonnie’s family treated our new German friends like hometown heroes. And we didn’t have much in the way of food, but they offered them our last few cans of beer and we broke out the cooler full of snacks and feasted them as best we could. I didn’t need to do anything but sit by the river with my new friends, and the beer and food and welcome was brought by the rest of the less tired family. I’ll never forget it, because it was the first time I felt like Bonnie’s family was MY family, and I was so, so grateful that I was a part of this family that knew how to show love and gratitude to strangers with whatever was at hand. I was lying in my bedroll that night, trying to think about why it was that such a simple meal, such simple gratitude, moved me so much. Was it just because I’m a minister and a Christian and Jesus was someone who also valued meals and who sat and ate with strangers and served the table? That must have been a part of it, but there was something more. I let my mind wander, and I found myself thinking of Thanksgiving dinners as a kid. I’m a big fan of Thanksgiving, in general. It is the greatest American holiday. It was invented by Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the Civil War. Lincoln saw Thanksgiving as an antidote to the forces that were tearing the country apart. How do we face the horrors and the grief of this war? With a meal, with our family, with Thanksgiving for the blessings we have received, and maybe that will help sustain a hope in our hearts that this national division that separates us from our neighbors is not permanent and may one day know peace again. Maybe Lincoln knew that a young, vibrant, changing democracy like the United States would always need a holiday like this. In some ways, on a national level, Thanksgiving is even better than Christmas, because EVERYBODY in our country celebrates it. North, south, east, and west, black white, and brown, Muslim, Christian, Jewish, atheist, republican, and democrat, expats gone for decades, and immigrants who have just arrived, we all celebrate Thanksgiving. In our reading from Deuteronomy, another source text and origin story for Thanksgiving, when you had your harvest feast of Thanksgiving, you made sure that even the aliens in your land were invited to celebrate too. NO ONE was supposed to be left out. There is a deep spiritual truth here. If you are truly blessed, and if you are truly grateful for that blessing, you’re going to have at least little something for everyone. No one can be left out! Your Thanksgiving should be more than a private pious moment, it should be a celebration that benefits even the strangers you barely know yet. I learned that as a kid at my family’s Thanksgiving table. When we celebrated, the whole family got together, the food was always plentiful, and there was almost always somebody else at the table. For instance, my grandfather had a neighbor for many years. His wife and he never had children and had no close family. When his wife died, my mother started to invite him to Thanksgiving dinner. She wasn’t particularly close to the man, she just knew he needed a place to be, and so she invited him, and he came and celebrated with us for many Thanksgiving meals. And he wasn’t the only one. If we knew someone might need a place, they got an invitation. And so that reason I was so deeply moved by my new family’s hospitality to three foreign strangers who visited our camp was because of the lessons I had learned at my family’s Thanksgiving table. This is how you prepare for the whole nation’s holiest day. You stuff the turkey, you bake the pie, you have the whole family over, you hold hands together around the table and say grace and give thanks to God, AND don’t forget to invite a stranger or anyone else who might need a place to sit. And, of course, this is also my best vision for what a church should be—not a private prayer chapel, not a cavernous holy space where you can get lost in the alcoves. Those are wonderful things too, but church at it’s best is a community of people who have woven their lives together with gratitude and love and fellowship and faith in such a deep and meaningful way that when strangers and new friends pass through our community, there is something for them to grab a hold of, there may even be a safety net of love that can catch them and hold them in their time of need. This is my point. A church that knows the true meaning of Thanksgiving is not just a collection of individuals who feel grateful, it is a community that believes holiness is made complete when we invite a new friend to join us. Preaching on: Luke 21:5–19 What lasts? Really lasts? In a world where things are constantly changing, and where disaster seems to always be right around the corner, and where there is endless turnover in trends, and truths, and regimes, and borders, what really lasts? What do you think? Maybe nothing truly lasts. Maybe eventually everything is gobbled up by the inexorable woodchipper of time. Maybe everything is eventually lost. Maybe, but I don’t think so. And I don’t think Jesus thought so either. Jesus, I think, wants us to know that the things we typically think are going to last aren’t the things that are really going to last. Jesus doesn’t want us relying on the wrong things—things that eventually rust, or get eaten by moths, or get knocked down. He wants us to experience the things that really do last.

Take the Temple in Jerusalem. In Jesus’ day it was the center of religious, political, and economic power. That seems like a place that ought to last! And it was huge too. It covered 35 acres. A NYC block covers five acres. Imagine 7 city blocks, and it’s 14 stories tall at its highest point. That seems like something that should last, doesn’t it? And did I mention it was made entirely out of stone? There’s this one stone in the Western Wall that we think is the largest stone ever used in construction in human history. You might be able to squeeze that stone into our sanctuary if you took out a couple of walls, but the problem is that it’s so heavy that nobody alive today has any idea how to move it. That seems like something that should last! And by the time Jesus came along the Temple was already like 600 years old. Doesn’t that seem like something that’s just going to be there forever? But while everyone else is admiring the architecture and the stonework and the views, Jesus reminds them that even this Temple—this ancient, stone seat of power and the center of their world—will not last forever. And he was tragically proved right. About four decades later the unthinkable happened—the Temple was utterly destroyed by a Roman army during the sack of Jerusalem. Now, this might feel disappointing to you if you were hoping that Jesus’ mysterious words in our scripture reading this morning were about the Apocalypse—some vague notions of the end of the world cobbled together with little pieces of the Bible taken out of their original contexts. I hate to disappoint, but Jesus was not talking about some event in our future. He was talking about an event in his future, now far in our past. But he was also making a larger point, wasn’t he? Even the Temple will one day be gone. If it hadn’t happened in the year 70, it would have happened eventually. Wars, insurrections, earthquakes, famines, pandemics, comets and asteroids—eventually something is going to take us out. Scientists tell us that the whole Earth will be gone in five billion years and the sun in 10 billion. And some billions of years after that the entire universe may just stretch itself out into an empty, cold, lightless infinity. So, what really and truly lasts? When confronted with the possibility of the apocalypse or an apocalypse (little apocalypses are happening all the time—a divorce, a job loss, a cancer diagnosis, a natural disaster) when we face these possibilities, one response is the fear response. The fear response says, I should try to placate the power in charge of apocalypses so that apocalyptic things don’t happen to me. I will believe in God, so that God will protect me from all the trials and tribulations of the world. This perspective finds it’s “highest” expression in the entirely made-up “doctrine” of the Rapture—in which obscure biblical verses are strung together to suggest that at the beginning of the looming end of the world all the good, believing Christians will be whisked away to Heaven and the ungodly along with all the other religions of the world will have to suffer the plagues and wars of the end of times all alone. I mean hadn’t you heard? Bad things never happen to good people! That just wouldn’t be fair! Jesus puts it simply for his followers (not for his non-followers, he said this to his FOLLOWERS): You will be arrested, persecuted, imprisoned, tried, and hated. You will experience division, betrayal, and the loss of family and friends. And some of you will even be executed. And then Jesus says something very strange. He says, “But not a hair of your head will perish.” That’s a very strange thing to say to someone you’ve just predicted may very well be put to death. Well, they’re going to kill you. Yeah, they’re definitely going to do that. But don’t worry about your hair. Your hair is going to look great the whole time. No, I think it’s almost like a riddle. You may suffer. You may die. But not even one hair of your head will be lost. Because, beloved, whatever trail or tribulation you may pass through (and you can be certain that you’re going to pass through some) Jesus wants you and me to be the things that truly last. Jesus wants us to endure. And when we endure, he says we gain our souls. In the turmoil of the world and in the trials of our lives, it is our authenticity, our forthrightness, the expression of our character, our truth, and our selves that matter most. Life is hard. But you have a destiny—God’s plan for you. This destiny, these plans, are built into your life, they are a part of you, they are you. Now, when tragedy strikes in your life, as it probably has before and certainly will again, the person who God made you to be doesn’t suddenly go away. In fact, sometimes it’s in the walk through the valley of the shadow of death that we discover more deeply who it is that God made us to be and we can express more fully what it is that God gave each and every one of us to express. Do you believe that? Do you believe that you have a destiny, that God has a plan? Do you believe that there is something inside of you that God created in you and that your life—its joys and its sorrows—is just God’s way of giving YOU every opportunity to come out as fully as possible? If you don’t quite believe it, let me suggest a prayer you can pray starting today. Pray, “God, I believe that I am here for a reason.” It’s a very short prayer. It’s like a breath prayer, you can pray it all day long on repeat, if you want. But even if you just pray it a few times a day, take the time to pray that prayer. I am here for a reason. When you pay attention to your life and when you walk out into the world with that prayer in your heart, you might begin to see your opportunities a little differently. We have a couple pairs of prayer partners in our congregation this month. Prayer partners, why don’t you discuss this together. What am I here for? We need to live this question out as the question of our lives, at all times. We need to believe that whatever we face, when we are living faithfully to who God intends us to be, the expression of those gifts will outlast stone and outshine the sun. Do you believe that? Can you believe that an act of simple generosity or human kindness or music making or falling in love will last longer and matter more than all the stars in the sky? Do you believe that something will last? Do you believe that you’re a part of it? God, I believe I am here for a reason. Amen. “Once there was a tree… and she loved a little boy. And every day the boy would come and he would gather her leaves and make them into crowns and play king of the forest.” How many of you recognize that? Those are the opening lines of one of the most popular and celebrated children’s books of all time, The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein. You’re familiar with it, right?

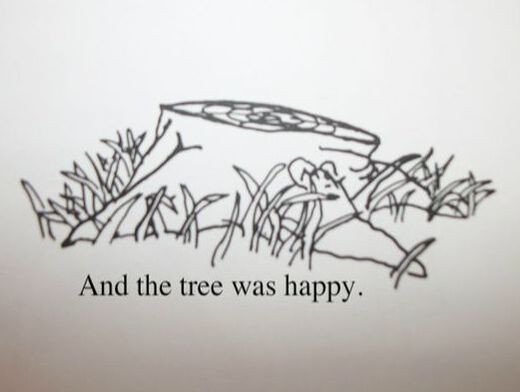

And this book has many fans. Many fans. You may be one of them, yeah? So, it is with some trepidation that I confess to you all that I am not a fan of The Giving Tree. I think its story sends us all the wrong messages about giving. And this morning we’re going to talk about those messages in order to help us understand the meaning of Jesus’ parable from our scripture reading this morning, which I’m calling The Parable of the Ungiving Tree. Now the reason we’re talking about all this this Sunday is because we’re nearing the end of our church’s Stewardship Season, which this year we’ve themed “Cultivating Community.” Next Sunday is Consecration Sunday, so we’re asking you over the next week to really think about what you can give to this community in 2023, we’re asking you to write it down on your pledge card, and we’re asking you to bring it to church next Sunday for a blessing. If you’re not here on Sunday, you can mail us your card or just pledge online, but we want all your pledges in by Sunday, so this is the week to decide if and how and why you are going to give to our community. Giving is always good, right? The Giving Tree starts out OK, as you heard. The tree loves the boy, and the boy loves the tree. The boy climbs the tree, swings in the tree, plays with the tree, sleeps in the tree, hugs the tree. And the tree is happy. But as the boy grows things take a turn. The boy is distracted by his expanding life and the tree is left all alone. When the boy finally returns to the tree he doesn’t want to play anymore. He wants money. So the tree offers her apples to the boy so he can sell them and make money. He takes all her apples and leaves her all alone again. Much later, the boy returns and now he wants a family. So the tree offers all her branches so the boy can build a house. And he takes them all. The boy returns again as an older man and wants to go on a voyage, so the tree offers her trunk so he can make a boat out of it. Now this tree, once full of leaves and apples and swinging branches and life and joy, has been reduced to a stump. And the boy returns one last time as an old man, looking for a place to rest. And the stump that was once his beloved tree offers him a seat on top of her. And the final image of the book is an old man sitting on a stump, staring off into the blank emptiness of the page. And the text next to it reads, “And the tree was happy.” Really? So, I have to ask, what kind of love is this exactly? Is this supposed to be a model for our relationship to nature? We can just take and take and take? Strip mine the mountains, pollute the atmosphere, overfish the oceans, and clear cut the forests. And when we’ve killed our happy planet, we’ll just what—sit content on the stumps of the earth? Where’s the Lorax when you need him? Somebody needs to speak for the trees! But this is the fundamental flaw of The Giving Tree—the Giving Tree has no needs other than wanting to give. And that’s a dangerous fantasy. There is no such thing as a tree or a friend or a wife or a husband or a planet or a church or anything else that only wants to give you what you want and does everything to make you happy without needing anything in return. Does NOT exist. What about parenthood? Maybe parenthood feels like this sometimes. But if Bonnie is ever an old stump of a woman, exhausted from giving her all to her family, and then her grown son comes along because he wants something instead of showing up to care for her, I will know that I have failed to teach my son some pretty important lessons about love and respect and honor. Even your mother needs something in return. I Love You Forever is my favorite children’s book about mothers and sons. The mother gives so much care and love to her son, but at the end of the book when she’s old and sick her son returns the care she gave to him to her. Then he goes home and he rocks and he sings to his baby daughter just like he had been rocked and sung to when he was growing up. Because part of growing up is learning to give back and to pay it forward—messages painfully absent at the stump end of The Giving Tree. And so some people say that it’s true that no person, no planet even, can love you like this. No, earthly mother can love you like this, but your heavenly father can. Doesn’t God give us everything? And doesn’t God love us no matter what? And didn’t Jesus dies for our sins? Well, yes and no. The boy in this story gets everything he asks for, but it costs him nothing. And that’s not how God works. God’s grace is not cheap. Cheap grace is the kind of grace that gives and gives and gives without ever asking anything of us in return. But the grace of the Gospel is transformational grace—grace that demands—from within our own hearts and souls—that we change, that we sacrifice, that we confess, that we forgive, that we reconcile, that we care for one another, that we care for the least of these. The boy in The Giving Tree he grows, but he never grows up. Even when he’s an old man the book it just calls him “the boy.” He doesn’t change. The tree gives the boy everything he wants without requiring him to grow up, to give back, or to pay it forward. Just imagine how healthy it would have been for this bratty man-child to have heard that tree say, “NO.” Imagine what might have happened then in that discomfort. And so we come to Jesus’ Parable of the Ungiving Tree. The boy shows up at the tree wanting some figs instead of apples this time. And the tree says, “NO! NO FIGS FOR YOU!” And the boy storms off. He comes back the next year and still no figs. And the next year same thing! He’s indignant! “This tree of mine that I have neglected except to come and demand figs of it when I am suddenly in the mood for figs is not meeting my needs! CHOP IT DOWN!” If we’re being honest, we all have this boy inside of us to some extent. This boy has ruined marriages and friendships, caused us to yell at millions of perfectly polite customer service representatives just trying to do their jobs, and to do even crazier things—I recently got furiously mad at a new diaper pail Bonnie bought because I didn’t think it was designed well enough. That’s right. I didn’t think a pail was designed well enough for me to throw my baby’s poop in. This boy inside of us, he thinks he’s hot stuff, but really, he’s a ridiculous child. Luckily for us, this is where Jesus shows us his alternative to demanding that the world suit our needs. When the boy who owns the vineyard tells his worker working in the vineyard to cut down the tree, this worker, this gardener begs for more time. Let me care for this tree. Let me fertilize it. Let me give it what it needs so that it can produce figs for everyone. The part of us that wants figs and wants them now is always a little louder. That’s why he owns the vineyard. But all of us have this other voice in us as well. And though it may be quieter, and less powerful, Jesus tells us that the gardener’s way is our true destiny as Christians. Because Christians don’t give up. We don’t lose hope. We don’t make demands—we give ourselves over to God’s will and we act for God’s Realm. We don’t think only of ourselves. We dedicate ourselves to serving others. We get our hands dirty. We don’t just consume the figs. We cultivate the figs. As you consider your pledge for 2023 over this final week of stewardship season, don’t think of it as trying to cover what you have consumed. Think of it as empowering our church to grow and to thrive beyond your personal needs. Give because your neighbors have needs. Give because this church has needs. Because there’s s no such thing as the giving tree. You can’t be one. And neither can your church. If you’re going to be a part of this church, you should know that there’s a chance that one day you’re going to need figs, and you’re going to show up to church looking for figs, and there won’t be any figs. There are three possible responses: 1. You can hope it was just a bad day and come looking for figs some other time. 2. You can move on to another church and hope that that church is a true giving tree and that it has all the resources that it needs to always meet your need for figs. 3. With the hunger for figs in your mouth, you can join Jesus at the roots of this tree, with your hands in the dirt, and you can cultivate your community. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed