|

The story goes that someone once asked a rabbi why it was that in the old days God used to show right up and speak to people and be seen by them, but nowadays nobody ever sees God anymore. The rabbi replied: “Nowadays there is no longer anybody who can bow low enough” (related by Carl Jung in Man and His Symbols).

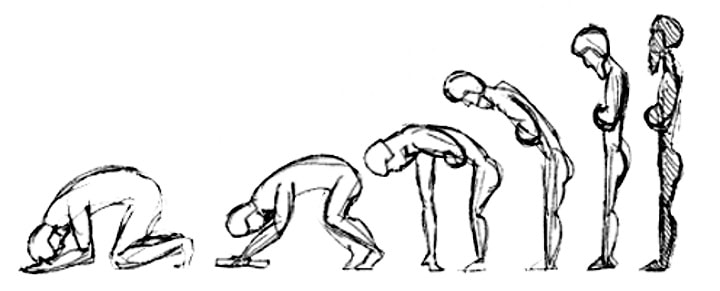

This morning, the first Sunday of Lent, I want to talk to you about humility—about the possibility of bowing low enough. If not bowing low enough to see God like in the old days, then at least bowing low enough to see and to hear a little more of the truth. And what is the truth? At least bowing low enough to see one another. Because seeing one another and hearing the truth that comes from another person’s mouth, another person’s experience that is different than ours, is not easy. To encounter the truth that is bigger than ourselves requires a spiritual shift in perspective. I’ve been thinking a lot about what that shift in perspective is—about how to describe it. And I know that at least part of the answer, part of the low bow to God and to our neighbors, is the cultivation of the virtue of humility. The first thing we need to discuss in a little more detail is humility’s public relations problem. Just like any virtue, if practiced without intention, and without awareness of context, and without concern as to its effects on the practitioner or upon others, then humility can be transformed from a virtue into a tragic character flaw—a deadly sin. It is possible to believe that we’re being humble when really we are being dangerously self-deprecatory or docile in the face God’s will. Our prayer of confession this morning put it nicely (Marlene Kropf, Congregational and Ministerial Leadership, Mennonite Church USA): I pour out my sins of pride, unbending, unyielding arrogance, self-righteous zeal for perfection, damning judgements, vicious grasp of my own destiny. AND… I pour out my sins of refusal to take my place, cowering fear, spineless accommodation, failure to speak, unwillingness to be counted. We also have to remember that in this country for hundreds of years, much of what was preached as the supposed Gospel of Jesus Christ was, in fact, nothing but slaveholder religion—a moral abomination and a Christian heresy that told Black people held in the bonds of slavery that they should be meek and humble and compliant and accept the yoke and the rod of slavery as God’s good intention for them. And that sentiment is still in the system, it’s still out there, it’s still preached. The context and the language have been updated, but we haven’t completely exorcised slaveholder religion from American culture or from American Christianity. And so we must be careful about who recommends humility to whom and to what ends. Similarly, women in our churches have always been expected to display the virtues of humility more than men. For thousands of years, we have asked women to step back, to quiet down, and to cover up. When they have complained about their oppression or their abuse, the Church has often told them that this is their cross to bear—with the grace and humility appropriate for their sex. And so we must be careful about who recommends humility to whom and to what ends. Humility can be thought of as a kind of submission, but it must always be a submission to love, a submission to righteousness, a submission to justice, to fairness, and to equity, and never to their opposites. When we are truly humble, others may laugh at us, others may jeer at us, others may disrespect or even attack us, but true humility leaves us empowered and in control—we are humble, we are never humiliated. The Black and White protesters who sat in at lunch counters throughout the South to protest segregation were howled at and beaten. They had food dumped over their heads, they had cigarettes put out on their arms. They were called vile names. They didn’t fight back physically. They let that hatred break on them like a storm on the rocks. And then the police came and hauled them off to jail. When in court they were given a choice of paying a fine or spending a month or more in jail, most of the protesters took jail—not because they couldn’t afford to pay, but because they wanted to show the powers that be that they could withstand the worst that the system could throw at them. The segregationists told Black people to stay humble and to accept their place. Instead, the Civil Rights Movement used true humility to throw the mighty down from their thrones—because sometimes heaven shall not wait. Just as a false sense of superiority is not humility, neither is a false sense of inferiority. True humility is about finding the real sense of who you are, who God created you to be—not too big, not too small. One of our Lenten themes this year is “Lent of Liberation: Confronting the Legacy of American Slavery.” I’m reading a Lenten devotional by that name and you all are invited to join with me in reading and discussing the text this Lent. As I’ve been reading and preparing myself for Lent and reading about the struggle for racial justice and even just the conversation around racial justice—how we talk about race and racial justice, I feel like our greatest challenge to seeing, believing, and acting on the truth is our limited perspective—a truly human problem, built right into our essential nature: None of us knows it all. That right there is reason for humility. Instead, what we see is that if the truth is convenient to us, we accept it. Because you don’t ever have to bow to a convenient truth. You don’t ever have to bow to a convenient religion, to an expedient morality, a cheap grace, an easy God. But when the truth is complicated and difficult to understand or when the truth convicts us or feels uncomfortable to our opinions of ourselves or our lifestyle, we don’t wanna bow. And much of the time, we may not even be aware of the mental and moral gymnastics we’re performing in order to keep our backs straight and our knees unbent. If only we could see as God sees! But Psalm 139 tells us that “such knowledge is too wonderful for me; it is so high that I cannot attain it.” And we can never attain it by going high. The only way available to us for getting closer to God’s perspective is to go low—to take the Lenten path, to bow a little deeper, to make a practice of humility. The Psalm concludes, “Search me, know my heart, test me, know my thoughts. I won’t try to hide from you anymore because you know me completely and I’m going to stop pretending that you don’t—even my sin, even my wickedness, I’m going to give it to you, so that you can lead me in the way.” You can only sing those lines from a downcast position. To sing them and to mean them requires the lowest kind of bowing down there is—the surrender of the soul to grace and to love. It is not the position of the know-it-all, not the position of the authority, not the position of someone who has locked onto the perspective of their own ego to the exclusion of all competing perspectives. Someone once asked Jesus, “What is the greatest commandment?” Jesus said love God with all your heart, all your soul, and all your mind. And a second is like it: Love your neighbor as you love yourself. And a second is like it. These are not two arbitrary and unrelated commandments. They are deeply connected. So, if you are going to bow low to God’s perspective, you also have to bow low enough to hear your neighbor’s perspective. Wait. What about the flat earthers? What about Qanon? What about neo-Nazis? Am I really supposed to bow down to their conspiracy theories and lies? No! Absolutely not. In the documentary John Lewis: Good Trouble, Lewis tells us that when civil rights protesters went out to perform non-violent civil disobedience, it was his intention to “look my attacker in the eyes.” We’re not bowing down to anyone’s opinions or to their hatred, we’re bowing low to the Image of God within them. Our neighbors are not always right. In fact, a little time on your neighborhood Facebook group will prove to you that your neighbors all disagree. We do not bow low enough to hear our neighbors’ perspectives because they are right, we bow low enough to listen to our neighbors because that is a part of loving our neighbors. I do not bow low enough to hear my neighbors’ perspectives because they are always right, I bow low enough to hear the perspective of others because I am not always right. In Jesus’ parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man we see the consequences of being too high and lofty to bend our ear to the experience of another person. I can imagine that the rich man had all sorts of excuses for remaining comfortable with Lazarus lying at his gate and suffering. We continue to hear these excuses today—sometimes they come out of our own mouths: “Well, Lazarus he must have taken a wrong turn in his life to have ended up like that. He must have done something to deserve it. He must have gotten himself addicted. He must not have worked hard enough. I bet he makes a lot of money sitting there and begging all day. Not to mention how much we give in taxes to clean up after problems like him. And you don’t get sores like that all over your body unless you’re not careful—I can’t be blamed for his “lifestyle choice.” And haven’t I worked hard for everything I’ve got? Don’t I deserve to enjoy it? Shouldn’t I be able to take a break and not have to worry about people like Lazarus?” We’ve all had judgmental and haughty thoughts like this that accounted ourselves too high and other people too low. And Jesus tells us in the parable that when we aren’t serious enough about the absolutely necessary spiritual practice of bowing low enough to hear the perspective of another, we fix a great chasm between ourselves and others that is impossible to cross. Those of us who have privilege—and many of us do, whether it be male privilege, or straight privilege, or white privilege, or the privilege of economic status or educational degree or citizenship—those of us who have privilege ought to pay close attention to the fate of the rich man. Lazarus was already humble. It was the rich man who needed to learn to bow. But he didn’t. So, this Lent I recommend to you a practice of an empowering humility. We have tried recently to solve our problems in this country with arrogance, with bitter fighting, and without consideration of any kind for our neighbors. Many of our fellow citizens are committed to that path. But it is a path to hell and destruction for ourselves and our neighbors. We cannot force anyone off that path they’ve chosen. Abraham says it clearly, “If they do not listen to Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.” My responsibility lies with me. I can choose to step off the path of destruction. I can choose to listen with empathy and compassion to my neighbors even when their truth makes me feel uncomfortable. I can choose to emulate the humility and strength of John Lewis, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr. I can choose to bow lower than I have ever bowed before.

0 Comments

|

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed