|

Preaching on: Matthew 25:31–46 Today is Amistad Sunday in the United Church of Christ. I wouldn’t be too surprised if some of you don’t know the story of the Amistad or, if you do, why do we celebrate it as a special Sunday in the UCC. I’m going to tell you some of that story today because it’s one of the most important stories in the history of our country and in the history of the UCC. It’s so important to our denomination that it defines the ways that we think about our mission, our calling from God, and how we define our ultimate concerns as the followers of Jesus. So much so that we’re going to have to get into the question raised so powerfully by our reading this morning—what is the substance and character of salvation?

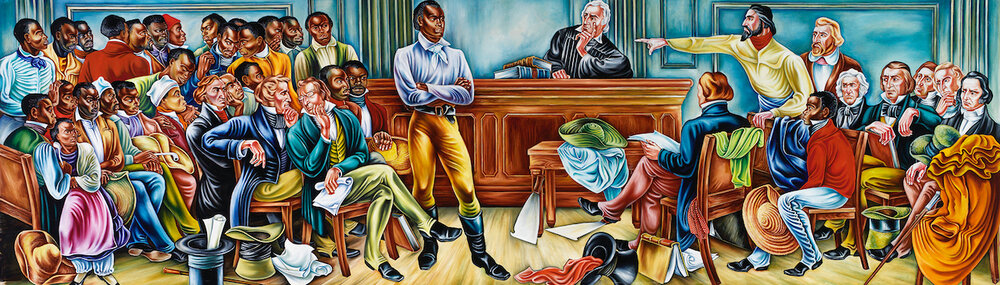

When our Congregational ancestors, the Pilgrims and the Puritans, first began arriving in the New World in 1620, it was more than year after the first African captives were sold as slaves in Virginia. That fact always strikes me. We sometimes mythologize the Pilgrims as the beginning of America. But for more than a year before they landed at Plymouth Rock there were Black people enslaved in the tobacco fields of Virginia. This is also our national origin. We know that a small group of Congregational Pilgrims came to the New World to escape religious persecution in England. But the much larger waves of Congregational Puritans who arrived after them had a different purpose. That purpose was stated best by John Winthrop. He said, “We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” What he meant by that was that their colony was going to be a perfect Christian society, a vision of the Kingdom of God so powerful that it would reform and purify the values of England from across the ocean, and all of Europe would be transformed by the light of their righteousness. In the earliest spiritual DNA of our Congregational ancestors there was a desire for a social transformation on the earth, in this life, that knew no boundaries. This was one of their ultimate and motivating concerns as Christians. It was their calling from God. How did it go? Not so great. Slaves were brought to Massachusetts in 1630. Slavery was fully sanctioned in the early 1640s. Then from 1675 to 1678 one of the most brutal wars in American history took place between the Puritans and the Wampanoag and the Narragansett Native Americans. The Wampanoags were the very same people who had kept the Pilgrims alive through their first difficult years. But by the end of the war both tribes were nearly destroyed, and they were left practically landless. The Puritans wiped them out with a Biblical meticulousness—men, women, and children, whole villages gone, two nations nearly eradicated. The Puritans’ desire to transform the world was a Godly desire. Their methods were the worst kind of depraved, antichrist sinfulness. New generations of Puritans were being born in the New World. They had never seen England and never would. They would never even see picture of the place. It might as well have been on the moon. They didn’t care about it. Europe? What’s that? They weren’t interested in purifying any of these storybook places. They had New World problems. So later generations turned away from their parents’ ideals and convictions and turned their Puritanism away from the world and directed it all inward. Their ultimate concern was now the sins of individual soul and individual virtues: propriety, hard work, temperance, and prudence. Puritanism was done and we became better known as the Congregational Churches. That’s our origin—big worldly ideals reduced down to individual piety. And that’s kinda the way it went for a while. Fast forward to 1839 when Portuguese slavers illegally capture hundreds of Mende people in Sierra Leone, sail them through the Middle Passage to the Spanish colony of Cuba, and sell them into slavery. 53 of these Mende people were then being transported to a Spanish plantation aboard the ship La Amistad. Fearing for their lives, a young Mende leader named Singbe Pieh frees himself and others from their chains, they arm themselves with knives, and take control of the ship. They demand the crew sail them back east to Africa, but during the night the crew sails them west and they are eventually overtaken by a US Naval Ship. The Mendes were taken prisoner again (as pirates) and transported to New Haven, CT where a battle ensued over whose property they were. Were they the property of the US naval officers who claimed them as salvage, or were they the property of the Spanish plantation owners who bought them, or were they property of Queen Elizabeth II of Spain who owned La Amistad? President Van Buren wanted good relations with Spain and demanded the prisoners be handed over to the Spanish government as quickly as possible. But a group of abolitionists and Congregationalists had formed the Amistad Committee to raise money and organize people for the prisoners’ defense. They believed that the Mendes were legally free and not slaves because they had been illegally captured in Africa and not born into slavery (the transatlantic slave trade was illegal at this time). The case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Former president John Quincy Adams argued in defense of the prisoners and the court found that they were not slaves or pirates, they were legally free people who had every right to fight for their freedom. Singbe Pieh pleaded during the trial, “All we want is make us free.” Now they were free at last. But the work of the Amistad Committee was just getting started. They now had to fight to return the freed Mendes to Africa. In the meantime, the Mendes lived in New Haven, stayed in the homes of church members, and attended worship with them until 1841 when funding was finally secured, and they sailed home. The story of the Mende captives struggling for life and freedom and the opportunity to stand by them in their defense reawakened a sense of spiritual purpose in the Congregational Churches. Personal piety was being transformed again into a new movement for transformation. God was doing something new. The Amistad Committee joined with other abolitionist and multi-ethnic groups across the country in 1846 to form the American Missionary Association. It was the first abolitionist missionary society in the United States, and it was a driving force for abolition and later for equal rights and education for Black people. During Reconstruction more than 500 schools were established for the education of freed slaves, including 11 historically black colleges, many still operating today. And in 1999 the American Missionary Association became the Justice and Witness Ministries of the United Church of Christ which continues to advocate and organize for human rights, women’s rights, racial justice, and economic justice. And we continue to support that work through special offerings, like the Neighbors in Need offering we collect in October and through our church’s annual giving to the national UCC which is overseen by our own Ministry of Outreach & Mission. Now, ever since 1839, the Amistad Committee, and then the American Missionary Association after it, and today our Justice and Witness Ministries and the UCC in general have received criticism from those who believe that “social justice” should not be one of the ultimate concerns of Christians. Salvation should be the only ultimate concern of Christians. Whether or not there is justice and equity and fairness in this world is a distraction from the salvation of the individual soul, and it’s a distraction from spreading the message of the good news of Jesus Christ. In 1839 there were many who called themselves Christians who were convinced of this. There were slaves in the Old Testament, after all. There were slaves in Jesus’ day. There were slaves in Paul’s day and in the early Church. God doesn’t care whether you’re a slave or not in this world, God only cares that you accept your lot in life, carry your cross, and get saved. It’s not about the conditions of the external world. All that matters is the condition of your eternal soul. But then we read again what Jesus says at the end of Matthew’s gospel: For I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me… Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison, and did not take care of you? …Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me. And these will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life. And when we hear those words, we must realize that we cannot separate individual spiritual salvation from social justice for everybody. Put it another way—there is nothing, nothing in the whole world, no power, or oppression, or injustice that can separate any person from God’s love. And there is nothing that could ever stop an enslaved person (for example) from being saved by God. But the person who looks upon their suffering and distress and does nothing? The person who trivializes their oppression as beneath God’s concern? The person who can’t be bothered with all that drama and anger and can’t we all just get along? The person who refuses to bow, refuses to listen? The person who cannot cobble together the courage to look the hard truth in the eyes and to respond? What about them? Are they saved? Will they be saved? Let’s just say that in our scripture reading this morning Jesus offers us an unambiguous and urgent word of warning. I think that our spiritual ancestors’ experience with the Amistad Committee, helped them to see that Jesus’ call to “do unto the least of these” is not merely a call to individual acts of charity. It reconnected them to that powerful calling in their own spiritual ancestors to transform the world. But this time instead of war, they would make peace. Instead of bloodshed, justice. Not because the transformation of the world is salvation. But because without giving ourselves to the needs of the least of these, Jesus seems to say that we cannot truly give ourselves to him. I think for the Amistad Committee, for the American Missionary Association, and for much of the United Church of Christ today, transforming the world, making justice, fighting for freedom is about walking the walk of salvation. It is the only possible response to the freedom we receive in grace, to the mercy we receive in forgiveness, to love we receive in Christ, to the revolution of values that Jesus teaches us. And if we cannot find it in our hearts to respond to God’s love with love for our neighbors and to respond to God’s grace with justice for all, we are in spiritual danger of cutting ourselves off from God. If we trivialize our neighbor’s hardship, we trivialize God’s goodness. If we shrug off our neighbor’s suffering, we turn our backs on Jesus. Beloved, the good news is that our Church, the United Church of Christ, the UCC, has been fighting for racial justice for hundreds of years. We know how to do this. We have the resources. We know we’re not there yet. And we know that we are called to transform our world and our church into a vision of the Kingdom of God. Singbe Pieh said, “All we want is make us free.” Maybe we will only ever find true freedom when we answer God’s call to transform our world with love and justice.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed