|

Preaching on: Genesis 45:1–15 Last week we heard the story of the inciting incident of Joseph’s life: Joseph, a young, favored dreamer, is resented by his older brothers, who attack him and sell him into slavery in Egypt. This week, obviously, the lectionary has skipped ahead to the final resolution of that day. Here we are, years later, and Joseph is Pharoah’s governor, one of the most powerful men in the world. Using his dream powers, he’s saved Egypt from a great famine. His family is also suffering this famine in Canaan, and they run out of food. So, Joseph’s father sends the same ten older brothers who attacked Joseph to Egypt to seek aid for their family.

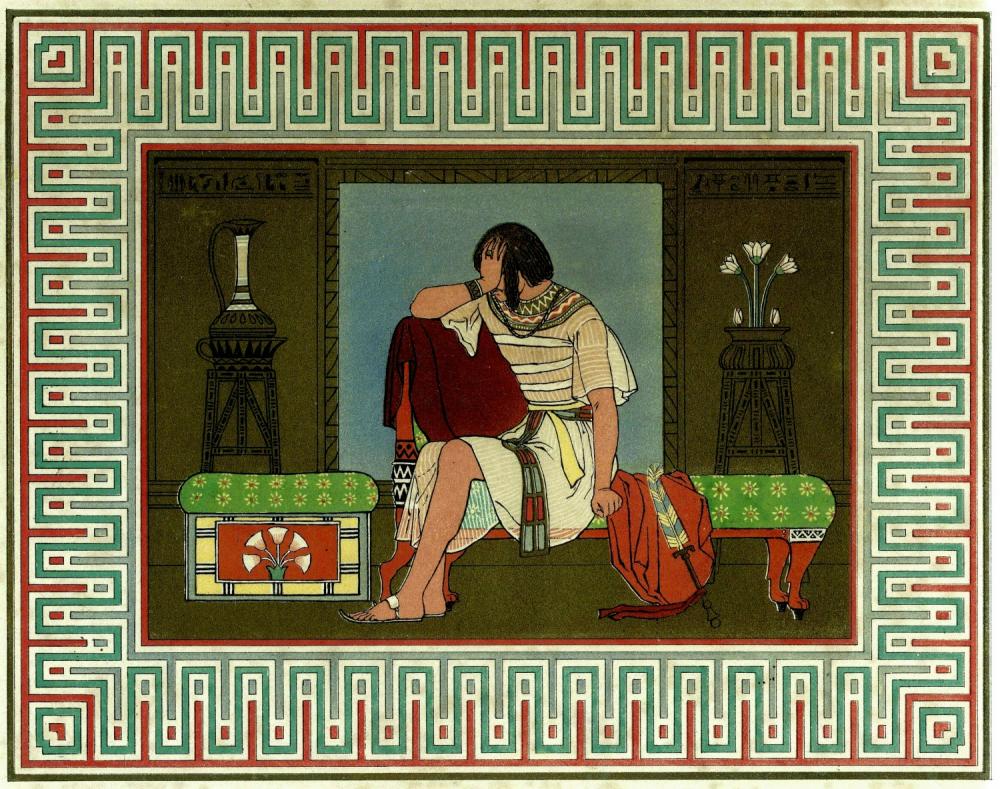

Our scripture reading this morning is “the big reveal.” Joseph has decided to reveal himself to his brothers and to offer them forgiveness and reconciliation. It’s a beautiful scene. And, of course, the lectionary has a limited number of Sundays to tell the story, and the editors wanted to “get to the good part.” And what’s the good part for a good, obedient Christian? Well, it’s the part where forgiveness is practiced, right? But I think the lectionary actually skips over the really good part. The lectionary assumes, from a Christian perspective, that forgiveness is the most important part of the story, and its natural conclusion. As if someone had commanded Joseph—or even advised him—to forgive his brothers, as Jesus has commanded us to forgive. But no one ever did that for Joseph. In fact, read the entire book of Genesis. There is not one single word in there about anyone forgiving anyone else under any circumstances. There’s one story about God considering forgiving some people, but then he destroys their city anyway. Forgiveness is not a virtue—it’s barely a concept—in the book of Genesis. Joseph has never heard the sermon on the Sermon on the Mount. Joseph has never read the Bible. He’s never even been to synagogue. None of that exists yet. And so how does Joseph come to this moment of forgiveness? The real story here is what comes in the chapters between the arrival of Joseph’s brothers in Egypt and this moment when Joseph finally reveals himself. The time between the brothers’ arrival in Egypt and our reading this morning could have been up to two years long. It was at least many months long. And Joseph goes kind of crazy. When his brothers first show up in Egypt, Joseph recognizes them, he knows exactly who they are. But he accuses them of being spies. He knows they’re not. But he’s in a sort of shock. He doesn’t know what to do. He throws them into prison. Then he decides to release them back home with food, but he’ll keep one of them hostage. And he’ll only release the hostage brother if the other brothers return with his little brother, Benjamin. But how does he even tell them he wants Benjamin without revealing himself? It’s a convoluted mess! How is this going to work? What’s he up to exactly? Is this revenge? Is this reconciliation? All that’s clear is that Joseph is in crisis. Now, not knowing that Joseph can understand them (he’s been using an interpreter to speak to them), the brothers speak right in front of Joseph about how all this is happening to them because of what they did to Joseph, and he has to leave the room to weep. A wonderful image, captured on the bulletin cover this morning, of Joseph in the heart of great personal struggle. So, after they pay for their grain, Joseph sneaks the money back into his brothers’ grain sacks, which seems like a kindness, but is actually a curse because now his brothers fear the Egyptians are going to think they’re thieves. His brothers return some months later after much conflict at home, with Benjamin, and there’s a whole another round of tricks. The brothers think they’ll be in trouble for the money, instead they’re given a feast by Joseph. All this time still not knowing it’s him. And Joseph again has to get up from the table to leave and weep. Now another trick: This time, Joseph puts his silver chalice in Benjamin’s sack and sends his guards after the brothers who drag the brothers back to Joseph as thieves trembling and afraid. Joseph tells them he’s going to have to keep Benjamin with him as a prisoner. But one of his brothers begs he be taken instead for the sake of their father who loves Benjamin most of all. And it is only at this point that Joseph can’t take it any longer and he reveals himself to his brothers. It’s becoming clearer now what’s been going on here. His brothers’ arrival has put Joseph into a moral crisis. What’s he supposed to do? He could kill them all and nobody would bat an eye. You know, revenge. Or better yet—justice! Why not? Joseph wouldn’t be murdering them, he’d be executing them, as is his right as governor. Or an eye for eye—just make them all his slaves. But how would that affect his father; how would it affect his younger brother? Joseph is a dreamer and surely his father told him about his own dream when God came to him and made him a promise about his family becoming a great nation. And what about Joseph’s own dreams? He dreamed twice of his family bowing down before him. Those two dreams affected him so much, he told them to his family, searching for an answer to them. They touched something deep inside of him. Those dreams were maligned and misinterpreted by his brothers as being nothing more than a desire for power and domination over them. But Joseph never felt that way—the dreams touched something deep within him—a desire to be more than he could even understand at that time. Do you see that this is the real story? This is Joseph’s great moral struggle. Not to forgive or punish. Not justice or reconciliation. That’s all there, but that’s not the heart of the matter. Joseph is asking himself over the course of these months of crisis: Will I stick to the call of my dreams to allow my life to be bigger than me—bigger than I have ever yet imagined it to be? Or will I succumb to the petty cruelty of my brothers’ way of seeing the world? Will I exact my revenge and thereby fulfill their interpretation of my dreams, and doom myself to being nothing more than a rich and powerful man? As Christians, we’ve been taught that we’re supposed to forgive. We don’t think it’s easy. We know it’s hard. But we think that it’s supposed to be easy. Like what we should all be striving for is to be such a saintly person that forgiveness is just no problem anymore. You just do it because it’s required. And so knowing that we’re not saints, we think that forgiveness and other great spiritual works are beyond us and we don’t try or we go through the motions, but we don’t really get all the way there. But when we think like this and act like this, we miss the whole point. The whole point is that forgiveness is hard. Forgiveness is so hard that to even contemplate it puts us—just like Joseph—into moral crisis. To get out of the moral crisis we have two choices: Give up or struggle forward. When we choose to struggle, to suffer this great moral crisis and not to run away, that is where the magic happens—that is where we discover that our lives can be bigger than us, bigger than we ever imagined. That is where God’s dreams for us can come true. In the struggle about what to do about his brothers, as Joseph kind of goes crazy and is doing all these weird and contradictory things, Joseph’s life is lifted up. Do you see that? The struggle is so hard that Joseph begins to realize that the meaning and purpose of his life is bigger than him, bigger than his goals, his desires, his justice. It is dreams which must define him—dreams which have always belonged to God. When Joseph realizes his best possible life is bigger than him, that’s when he can forgive. But he can only realize that inside of a great moral crisis and by struggling through it to discover a resolution which is beyond him. Joseph puts it into words like this, “It was not you who sent me here but God.” One of the most powerful lines in the Bible if—IF—you understand the struggle that got him there. If you think, “That’s just what we’re required to say—that everything is a part of God’s plan,” it falls terribly flat. You get mad at God for that. You did this to me? You start thinking what kind of a rotten God does something like that to a person? Because you’re not experiencing what Joseph is experiencing. In that moment, Joseph has stepped beyond himself and his own life. He is bigger now than he ever thought possible. This is not passive obedience to some difficult or distasteful article of faith. This is struggling with everything you have to resolve an impossible crisis and to discover in that great work that God has provided us with the dream and that grace to succeed in ways that will change everything. Beloved, Joseph's story shows us that the path of forgiveness and reconciliation is not easy or straightforward. Don’t forgive simply to follow some rule. In fact, when you encounter any great difficulty in life or in faith, don’t seek the easy way out. Take the winding road filled with moral struggle and crisis. When we open our hearts to God's great purpose in our lives, we will find the strength to travel that road. We are bigger than our wounds. Our lives are part of a greater story. May we have the courage of Joseph to step into the struggle. May we have the strength to stick with this agonizing inner work. May we have the faith to see that our lives are more than we imagine. God has a dream for us.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed