|

Madeleine L’Engle, the Christian novelist and poet who’s best known for her Wrinkle in Time series, was once asked in an interview, “Do you believe in God without any doubts?” She responded, “I believe in God with all my doubts.” It’s tempting to end the sermon there, but I’ll give you a little more…

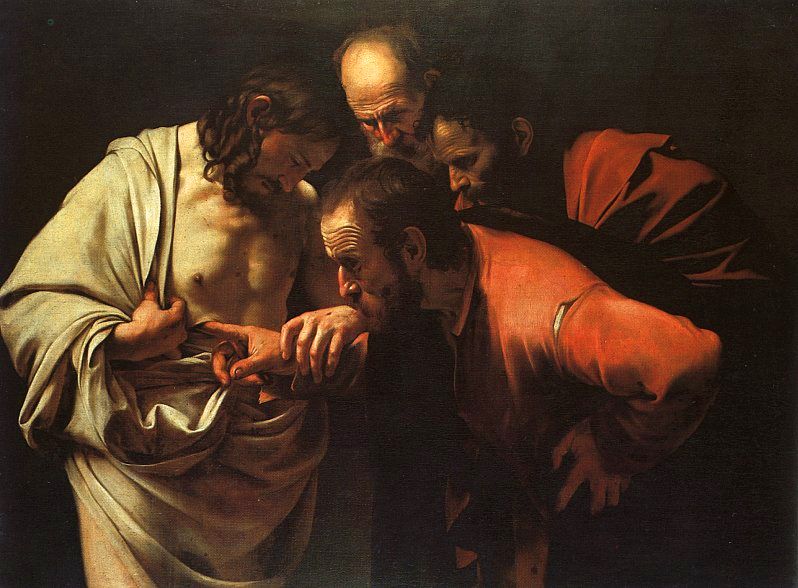

Because this brilliant line from L’Engle could really transform the way we think about “Doubting Thomas.” Do you know that in the Eastern Orthodox Churches, Thomas is not remembered as Doubting Thomas, but as Saint Thomas the Believer? In Luke and Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus famously says, “Seek and ye shall find!” Well, wasn’t Thomas a seeker in his moment of resurrection skepticism? Maybe Thomas found a little bit later than his friends, but he sought deeper and longer, and he had the integrity not to cave into peer pressure but to discover the truth for himself. I wonder, is Thomas’ doubt a closed door or an open door? Is Thomas’ doubt his excuse for calling it quits and breaking up with God? Or is Thomas’ doubt an invitation for God to enter in more deeply? Is Thomas’ doubt maybe an echo of that wonderful line from Mark’s gospel, “Lord, I believe! Help my unbelief!” I’ll tell ya, I think Thomas gets a pretty bum rap, poor guy. Thomas is remembered by us as the bad disciple, the one who didn’t quite measure up, the one with the special needs, the one we shouldn’t be like. I don’t think that this has anything to do with what Thomas said or with what he did. I think it has to do with our own feelings, as people of faith, of guilt and shame about the doubts that we carry—that ALL OF US carry, because no one is without doubts. So, I wonder if Thomas has something to teach us about living with doubt and really LIVING with it. The health of our doubt has to do with our perspective towards it—how we feel about its presence in our life and how we then express it. When Thomas got the news about the appearances that Jesus had made, something just didn’t click for him. It’s a whale of a tale after all. Jesus, Thomas has been told, has risen bodily from the grave. But when Mary first saw Jesus, she didn’t even recognize him—she thought Jesus was the gardener. And she didn’t touch him in John’s account. Jesus told her not to. Later, Jesus seems to materialize into a room with locked doors—something Spirits are well known for, but usually not bodies. The disciples saw the wounds of the cross and had the Holy Spirit breathed onto them, but they still didn’t touch Jesus. Thomas’ doubt is a bold statement of need. He has no self-consciousness about being public and clear. What I need, said Thomas, who had just lost a friend he loved deeply, is to touch him. If that wasn’t a ghost you saw, if it wasn’t just his Holy Spirit, then I want to touch his body. Thomas isn’t giving up here, is he? He’s certainly not being disrespectful. He’s not going to be poking at Jesus with a stick to make sure he’s solid. Thomas is seeking way more than “proof.” Thomas seeks and he doesn’t stop seeking until he finds his own intimate connection with the risen body of Jesus. How we deal with doubt affects the health of our entire lives. Doubt is not just something that assails us in church. Oh no. If only it could be that easy. If only all we had to doubt were the mysteries of faith, but we have our whole lives to find doubt in, don’t we? Love, relationships, vocation, self-worth, talent, happiness—we know how to doubt it all, don’t we? I was in a relationship once as a younger man in which we didn’t handle doubt well at all. We wanted to be together, and we loved one another deeply, but, wow, the doubting that we did was destructive. It’s not that doubt is inherently destructive. Doubt is normal and healthy. But we beat each other up with doubt. We weaponized it. Rather than using doubt as an opportunity to express our needs, we used it as an opportunity to accuse one another of the shortcomings we surely felt the other person had. Instead of using doubt to invite intimacy, we used it to create distance. Instead of using doubt to pay closer attention to one another and to seek together, we used it as an excuse to turn away from one another. Eventually, burdened under our ever-growing heap of doubt, our relationship predictably collapsed and buried us. We can heap this kind of doubt onto our loved ones, ourselves, or God. I call this kind of doubt “closed doubt.” We use closed doubt as an excuse to care less, to hope less, to try less, and to run away. But that’s not all there is to doubt. I call doubt spinning in the opposite direction “open doubt.” Open doubt is a very different animal. Closed doubt is sure of itself—absolutely not. Open doubt’s not so sure—maybe not. Closed doubt rejects. Open doubt wonders. Closed doubt says, “I’ve heard the stories, but I doubt there’s anything interesting on the other side of that old mountain. I doubt you could even get there if you tried.” Open doubt says, “I’ve heard the stories, and I wonder if there is anything interesting on the other side of that old mountain. I wonder if it’s even possible to get there. I wonder if the old stories might have a part in my life. It’s hard to believe, but I wonder…” I once heard a colleague of mine, Rev. Sekou, preach a sermon about faith. And he told this story about two women caring for a young child who was sick with fever. They didn’t have an icebox, so they had no way to cool the child off. So, one of the women took a bucket out from under the sink, put it out on the front steps, and came back inside, and then the two women together prayed for hail. Now when she put the bucket out, there wasn’t even a cloud in the sky, if I remember the story right. But God heard the prayers, God saw their faith, and God sent the hail for the sick child. I probably heard this story ten years ago now and it’s stuck with me. Putting out the bucket and praying for hail is a metaphor for faith. But I also think about the second woman in the story. There were two women caring for the child, remember. What was she doing in that story? She didn’t put the bucket out. And maybe she thinks this idea is as crazy as I thought it was when I first heard it. But when it came time to pray, she prayed too. That I think is a metaphor for open doubt—she left the bucket out on the steps and prayed even though she maybe didn’t believe. Sometimes imperfect faith and open doubt don’t look all that different. To be sure, Thomas is carrying a lot of emotion with him, in our reading this morning, right? He’s mourning, he’s afraid, he’s angry. Now everyone is telling him these incredible stories, and if they’re true, he’s missed the most important moment of his life because he was out doing the shopping or something. He’s exhausted. But he leaves the bucket out on the front steps, right? He sticks around for a week. God hears this as an invitation. And Jesus responds by offering up his body, his most tender places, his still open wounds, to Thomas’ touch—an honor the other disciples didn’t seek, didn’t ask for, and didn’t receive. Wonder is a key ingredient of an open doubt, but wonder can also be the outcome of open doubt—that wonderful moment when the hail hits the bucket. The numinous, awesome, terrific intimacy of putting your fingers inside the body of the resurrected Jesus—WOW! Wow… So, Beloved, my prayer for all of you this Easter is that you be a little kinder to your doubts and to yourselves and to all of us doubters. Doubt is a normal, healthy, and even a necessary part of faith. Doubts can be burdensome to carry, but I think that’s because we carry our doubts as our private shame—a social stigma, the reason we don’t belong, the reason we’re different than everybody else at church! But faith actually requires doubt because we don’t always have “proof.” The hail doesn’t always fall right when we need it to. But if we just leave the bucket out, open to the sky, we may be surprised by the ways that God can come to fill it.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed