|

Abraham is a fascinating figure. He’s portrayed in Genesis as a righteous and faithful man totally committed to his relationship with God. He’s brave and decisive when it comes to battle, but he’s also a compassionate peacemaker who prefers compromise to conflict. He admirably shows compassion to strangers through the hospitality of his table—he is willing to run out of his tent in the heat of the day to welcome in dusty travelers, wash their feet, and feed them. He’s so compassionate he’s willing, in one story, to argue with God to spare the people of Sodom and Gomorrah, two cities God has decided to destroy. And he’s so skilled in his argument that he cools God’s anger and apparently changes God’s mind. He’s a sly trickster, capable of persuading and manipulating great powers through clever reasoning or even by bold and audacious deceptions. There are many ways to admire Abraham, but let’s face it nobody’s nominating this guy for Father of the Year.

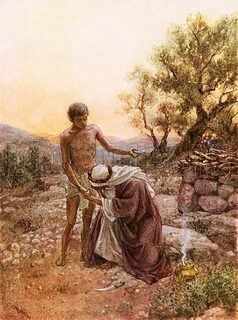

And maybe we just want to leave it at that. We don’t want to associate with anyone who would even consider participating in human sacrifice, let alone child sacrifice, let alone the sacrifice of his own child! Fair enough. We also don’t want to associate with a God who would encourage child sacrifice, even as a joke or a trick or a test. “Just kidding, Abraham! You passed the test! You can put the knife down now. Man, you should see your face!” Whaaat? It’s strange to think that God might prefer an obedient child murderer to a headstrong almost-anything-else. If I was in Abraham’s position, that realization alone would be enough to drive me mad—that the God of love and justice and morality, the God of care and compassion for the least of these, was actually a God so transcendent, so absolutely other, so powerful and so alien to us, that even the most obvious moral truths (like don’t kill your kids) could not be relied upon to satisfy Him. He could ask anything (ANYTHING) of you at any time and you would have to comply. That’s scary. That’s a horror story. We’ve been taught in the Christian tradition—taught through Jesus really—that God is a loving Father, who can be relied upon to care for us, to give us good things, and to (more or less) make sense. You don’t always get what you ask for, but whatever you do get is going to fall within a range of predictability. So, when we hear someone say, “God told me to kill my family,” we are certain, absolutely certain, that that person is just crazy. We don’t believe it at all. I don’t believe it at all, and neither should you. God wouldn’t ask that of anyone for any reason. But God asked it of Abraham. What? The easy thing here for us would be to dismiss it. Let’s just skip that part. Bunch of ancient superstition. Another way Christians deal with this is through the sanitizing power of orthodoxy. If I were preaching that sermon to you right now, I would simply tell you that Abraham was the pinnacle of faithfulness, willing to give everything to God, and we should emulate that; and that God was good and merciful by not ultimately requiring Isaac’s sacrifice; and we wouldn’t talk about all the disturbing and weird stuff that we would all feel underneath the surface. We would label all that stuff “doubt” and, again, we would just skip that part. Because we want to be in control. I believe that when you encounter something holy, like Holy Scripture, you are by definition not in control. God’s in control of Holy. Not me, not you. And when we enter into the Holy space of scripture or anything else God can do whatever God likes—we don’t know what’s going to happen. What don’t know what the message will be. An exclusively “literal” reading of scripture and orthodox interpretations of scripture that hog up all the space within a reading, are ultimately human attempts at controlling the Holy, at controlling God, of setting boundaries beyond which we are refusing to let God go. There are rules here, we say. And they’re our rules. And we expect God to follow them. But that’s not the way that Abraham sees things. Even though he’s a legendary trickster who has succeeded in arguing with God in the past, ultimately Abraham knows that he is not in control. And Abraham knows that there will arrive moments in every life where nothing is fair, where nothing makes sense, where everything we thought we could rely upon is yanked out from underneath us. There comes a time in every life where we will be called to sacrifice something we do not want to sacrifice. There will come a time in every life where there will be a loss so great that nothing can make sense of it. And when that moment comes, what will do? Whose example will you follow? This week, Ralph Yarl, the 17-year-old child who, back in April, was shot twice (once in the head) for ringing the doorbell at the wrong home while he was trying to pick up his younger siblings, he made his first public appearance since the shooting on Good Morning America. Watching the interview, I was struck by how much has been taken from young, beautiful, good Ralph Yarl and how none of it, none of it, makes any sense. Yarl describes the moment his attacker opened the front door to the house and thinking, “This must be the family’s grandpa.” And then he saw the gun and he froze in fear. And he thought, “He’s not going to shoot me. He’d have to shoot through the glass door.” He’s not going to shoot me. It wouldn’t make any sense. And then he shot him. Twice. Once in the arm and once in the head. And it changed Ralph Yarl’s life forever. His mother said that her son took the SAT in the 8th grade, but now his brain has slowed down. “A lot has been taken from him,” she said. But Ralph Yarl had no harsh words for his attacker. He wants justice, but he says he doesn’t hate him anymore. He says that he’s just a kid. He’s going to go on with his life doing the best he can and doing the things he enjoys. I worry for Ralph Yarl. I worry for the headaches he’s suffering from. I worry about the horrible emotional trauma he’s suffered. I worry about his brain injury and everything that’s been taken from him. But I don’t worry about Ralph Yarl’s soul. Because Ralph Yarl has faced that terrible altar of irrationality, that altar where nothing makes sense, where no amount of arguing or reasoning or resistance can save you, where something vitally important to you is taken away. Ralph Yarl has faced that altar and “given it up to God.” I don’t think our scripture reading this morning is about needing to be willing to become child sacrificers for God, if that’s what God requires of us. We don’t believe that God requires that. Because there is no reason for it and there is no excuse for it. But Ralph Yarl is a child who was shot in the head. And there was no good reason. And there is no excuse. And it doesn’t make any sense. And though he survives, a lot was taken away from him. It happened. And for Yarl to heal and move on with his life, he can’t get stuck in regret and bitterness. And so he has walked up to the altar that can’t be negotiated with, holding something precious, something no one, not even God had a reason or a right to ask for, and he has had to leave it there, to let it go, to give it away. There come times in our lives where we are asked to participate in our own loss, to participate in a loss that isn’t right, that isn’t fair, that isn’t moral, that we want no part of. In my own life, when my mother was diagnosed with cancer, I scribbled down as much information as I could—Stage IV Rhabdomysarcoma or RMS. When I was alone, I typed it into Google and started searching for mortality rates. The statistics for Stage I RMS stopped me cold. The statistics for Stage IV were unambiguously devastating. We took my mom to Dana Farber Cancer institute in Boston, about an hour’s drive from my parents’ home in Rhode Island. And the doctors looked everything over and one of them said to me very gently, very tactfully, “There are wonderful cancer doctors in Rhode Island, who I trust completely. I think your mom will be more comfortable closer to home.” I knew what she was really telling me: “There’s nothing I can do for your mom here that anyone else can’t do for her. It’s just a matter of time. And very soon the drive you just took up here is going to be impossible for your mom.” And I realized that even as I was doing everything I could do to save my mom, I also needed to do everything I could do to prepare for her pain, her suffering, and her death. I was being called on to participate in my mom’s death. You have no right, God, to ask me for that. No right! And yet, it’s a nearly universal human experience. About a year later, my mom was hospitalized and in terrible shape. The doctors had had to take yet more heroic measures to save her life—she had nearly died. And this was after radiation, chemo, major surgery, and multiple procedures. She was suffering and nothing was getting better, and she didn’t want to be stuck in the hospital. And when I visited her, she told me, “I think I’d be better off dead.” And she didn’t say it with any depression. She was standing at the altar of irrationality, where she was forced to confront a terrible reality that could not be fixed. And she was asking me to stand there with her. And I said, “Mom, when you see your doctors next you can tell them that you’re feeling like the time has come to go to hospice, and you can ask them if they agree that the time has come.” And she felt better. And that’s what she did. And the doctors agreed. And she went home to die. She was able to lay her life on the altar. And I had to do it too. And everyone who loved her had to do it or is still struggling to do it. That’s what I think Abraham’s story is telling us: that you have to be willing to part with the things you love most, the things it is most unfair to ask of you. Not just to part with them, but to participate in the reality that is taking them from you. And in the midst of that terrible journey to the altar of irrationality where no human effort can save you, you need to remain faithful and not lose hope in God. That’s what Abraham achieves. And it’s far easier to simply say, “We don’t believe in child sacrifice. God would never do such a thing,” but the deeper truth lies in the willingness to face the incomprehensible and the inexplicable and the unacceptable. It’s in those moments when our faith is tested, and the world seems to crumble around us, that we are called to trust in the God’s ultimate goodness, even when we cannot understand God’s strange ways. Faith is not always neat and tidy. It is a messy, uncomfortable, and often bewildering path. And you don’t know what is going to be asked of you. But you can be certain that it’s not all going to be nice or fair or easy. But it is also a journey of hope, of redemption, and the unshakeable belief that God is with us, even in the darkest of times, in the most difficult of losses. May we find the courage to face the altars of irrationality in our own lives, knowing that God who walks beside us, offering strength and grace, contains and cares for everything that is lost. And may we, like Abraham, trust in the goodness of God, even when God’s ways test our faith.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed