|

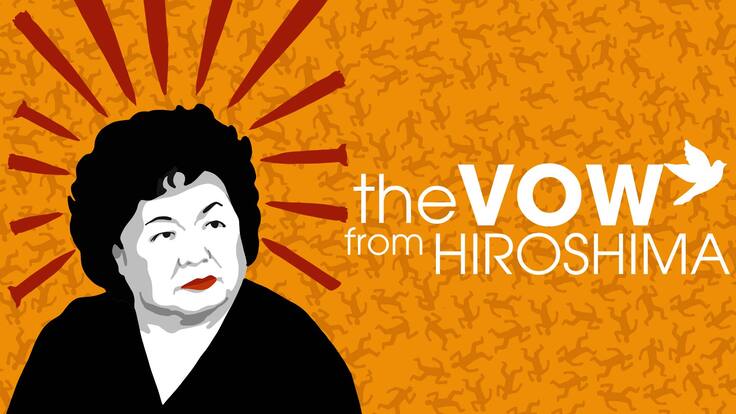

Well, I thought that I knew that I would be preaching on one of my favorite topics this morning. Jesus' love of disrupting the status quo for the gospel and the difficulties that we have with feeling good about the results of these disruptions to our world. But then on Tuesday night, here at the church, thanks to Tatsuo and Emiko Homa, we had a showing of the powerful documentary, The Vow from Hiroshima, the story of the life and work of Setsuko Thurlow who survived the atomic blast at Hiroshima at 13-years old. Listening to Setsuko's story and the horrors of what happened to her, an innocent 13-year-old girl, to her friends and her teachers, to her neighbors and her family when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, shifted my thinking this week. The disciples’ opening question to Jesus at the beginning of our scripture reading this morning, it began to stand out to me: Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?

And I began to hear it, not just as a judgmental question about sin, not just as a question biased against disability, but as a version of one of the human race's oldest questions. Why do bad things happen? You know, if God is an all-powerful, all-good, all-loving God, what is the justification for disaster and suffering and evil? How can an innocent baby be born blind if God is good? How could innocent babies be incinerated at Hiroshima? If God is good, why the Holocaust? Why 9/11? Why COVID-19? Why the earthquake in Turkey and Syria? Scripture has a number of different perspectives on this question. And all of them, I think, ultimately leave us a little dissatisfied. Perhaps, back in the furthest reaches of human history, the gods were seen as a bit capricious. So the gods would do all kinds of strange and unexpected things, and sometimes it was good for us and sometimes it was bad for us. That was just the way things worked. The gods were chaos, and sometimes terrible things happened, and sometimes good things happened. When we get into the oldest layers of Hebrew scripture, we have a slightly different perspective. In that perspective, God is the one who rewards the good, and God is the one who punishes the bad. And by extension, if you are suffering, if something horrible has happened to you, you must be being punished for something. You've caused it in some way. You've brought it upon yourself. You might not know what it is, but you can be sure that you have offended God in some way. But then in those same Hebrew scriptures, there is the story of Job. And Job's story, and is a direct repudiation of this whole way of seeing things. Job is a blameless person who suffers more than anyone could ever be expected to suffer. Everyone tells him, Well, you must have done something wrong! And he is sure that he did not. And he holds the line and says, I did not sin. I didn't do anything to deserve this. I don't know why I am suffering. And in the end, after all that enduring of suffering, he calls God down and says, God, you are going to make an explanation to me of why there is suffering. And God comes out of the whirlwind and God says, Look, I could explain it to you, but you wouldn't be able to understand it. So just be quiet and endure. That is your job. It’s not my job to explain things to you that are beyond your capacity. It is your job to be mortal, to endure, to do your best to survive. So it is no longer the case, according to Job, that if you suffer, it's because of sin, but it also doesn't provide an ultimate answer for why there is suffering and evil and pain in the world, which is very dissatisfying in some ways, isn't it? So, there are further developments and explanations. One of the developments (it's also there in Job) is that, well, there must be a good God and a bad God, right? And they're in a battle, a cosmic battle for the world. And there's good and evil because of this battle, and we have to choose sides. But as you get into the theology of the Hebrew scriptures in the New Testament, well, God is all-powerful, all-good, all-knowing, there is only one God. And so, even though we have a character in Christianity called Satan, who we like to blame a lot of the bad things in the world on, ultimately, since God is all-powerful and all-good, God could presumably stop Satan from doing the bad things. God could stop an Satan-inspired earthquake the same way God could stop a purely tectonic earthquake. And so when God becomes omnipotent, it becomes very difficult to understand how bad things are allowed to happen, especially to the most innocent of people. And in our culture and in our day and age, we understand deeply that terrible things happen to people who do not deserve it. There have been so many cultural moments through the 20th century and into the 21st century of just horrible, terrible suffering that has rocked the foundations of our entire culture's belief in goodness and belief in meaning and belief in God—the Holocaust, as one example of the kinds of events that have rocked us culturally and spiritually so that we can't get around them. We can't avoid them. We can't stop looking at them. In Setsuko's story from the Vow from Hiroshima, most of the children and teachers at her Christian girls school in Hiroshima were buried in rubble. They were at school when the atomic bomb went off and they were buried in rubble. Then the rubble began to burn. Setsuko made it out just by chance—somebody was able to free her from the rubble—and she stood outside her school listening to her friends and classmates buried in the rubble crying out to God for help and calling to their mothers to save them while they burned alive. And she had a nephew, a four-year-old nephew who was with his mother near the city center when the atomic bomb went off. And this four-year-old boy and his mother were so disfigured by burns and radiation, and their flesh was so swollen and sort of melting off of them, that the family could not recognize them except by the sound of their voices and the clothing and jewelry that they were wearing. Both mother and child spent days in agony begging for water, unable to see or hear or understand what had happened to them—days in agony before dying horrific deaths. And we understand that this is just a drop in the bucket of what happened at Hiroshima. And what happened at Hiroshima is just a drop in the bucket of the pain and the suffering that we can see experienced in this world, right? And so for many kind, loving, and reasonable people, this reality undermines their faith in God. How can I believe in an all-powerful, all-good, all-loving God who allows such things to happen? At the very least, it would seem like maybe a good reason not to want to get very close to a God like that, a God who can allow something like that to happen when we ourselves can't understand it morally. We can't understand it in terms of the compassion and the love that we feel. Going back to Setsuko's story, Setsuko, I think, became a deep mourner of the loss and the pain that happened at Hiroshima to all those people that she loved. She is a Christian, and she told us in the film that it was her Christian faith that really became the guidepost to her, the way to understand how she would become the person that she would become. And the person she became was not just a survivor, but a lifelong, totally committed and dedicated activist and reformer against nuclear war, nuclear weapons, nuclear proliferation, and the Cold War. Her tendency, no, her spiritual instinct was not to look backward at the tragedy and to get stuck there and to ask why, and to become mired in anger, not that, that we could blame her if she did do that. This is not a, this is not judgment against anyone who is mourning, right, but Setsuko allowed herself not to lose faith, but to move forward in service. She never let go of what happened. She carried that mourning with her all through her life, but that mourning did not become the question WHY? It became a response. What must I do now? And maybe at this point, thinking about her life, we're ready to hear Jesus' answer to the disciples’ question, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents that he was born blind?” Jesus responds, “Neither this man nor his parents sinned, he was born blind, so that God's works might be revealed in him.” At one level, we can see obviously here that Jesus is agreeing with the Book of Job: It is not your sin or your offense that is causing you your suffering. You are not being punished. Let's not look that way. But even more than that, it seems to be (and I got at this through Setsuko's story) that Jesus' major answer to the question of who sinned was to say, let's not look back to the original sin that caused all this. Let's not look back towards the answer for why things are the way that they are. Instead, let's look forward, let's move forward. And I'll just rephrase these words a little bit and maybe let you hear them in a different way, thinking about Setsuko’s story: Neither Setsuko Thurlow nor her nation sinned that the atomic bomb was dropped on her. She suffered so that God's works might be revealed in her. And in fact, God's works were revealed in Setsuko and her lifelong advocacy and work to stop nuclear weapons. In 2017, she was there and a major part of the organization, ICAN who lobbied in the UN to make sure that the UN's ban on nuclear weapons was passed in 2017, so that in international law, now nuclear weapons are illegal. We know that that has not made a big change in the world that we live in, but it is a major step for us as a world that nations around the world have said that these weapons are not acceptable to us. And also then in 2017, when ICAN won the Nobel Peace Prize, she was one of the people who accepted that prize, and she stood on stage and told her life story again and accepted the prize because ICAN recognized that she was the driving force of this. And she recognized that it was her Christian faith that was the driving force of the work that she had done for her people, for her family, and for everyone she had lost. God will never be revealed, God will never be revealed by trying to defend God or to blame God for the brokenness in this world, looking back and trying to find explanations is not the right direction. God is revealed when we respond to the brokenness of this world with deep mourning, and from that mourning, with service, with love, and with compassion for all of God's people, then God's works are revealed. Jesus said, blessed are those who mourn because I think that they, the mourners, are the only ones who truly know, truly understand the work that must be revealed, the work that must be done, how big it is, how important it is, and how devastatingly real the consequences of getting stuck and not acting for the betterment of this world truly are. So if you are a person who is filled with doubts about God, because you can't stop mourning for all of the souls that God didn't save, perhaps you too are blessed. I believe that you are almost certainly on the right path, and I encourage you to keep going. You know, one answer on this path is that there is no God. There is no ultimate good. There is no greatest love. There is no spirit that transforms lives. But I believe that that answer, that answer will never satisfy you, move you, inspire you as deeply as becoming an instrument of God's peace, and God's healing, and God's love. In a world that is broken beyond our comprehension or understanding, suffering cannot be explained away. It can only be responded to. There is no answer to the question of why the Holocaust, or why the earthquake in Turkey and Syria, why suffering because, perhaps, it is in wrestling with those very questions that God transforms us into the people who can feel the world's deep pain and who can respond with love.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jesus the ImaginationThoughts and dreams, musings and meditations Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed